THE REVEREND MR. TROTTY.

Chapter IV of THE TROTTY BOOK.

by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

Boston: Fields, Osgood, & Co., 1870 [c1869]

Note: Original illustrations should be black-and-white, but these have been hand-colored by a previous owner

Scanned by Deidre Johnson for her

19th-Century Girls' Series website;

please do not use on other sites without permission

NE Sunday it rained. Not that it never rained on any other of Trotty's Sundays, but that it did rain that especial Sunday.

NE Sunday it rained. Not that it never rained on any other of Trotty's Sundays, but that it did rain that especial Sunday.

Trotty sat on the window-sill, - it was a narrow window-sill, and he kept slipping off with a little jerk, and climbing up and slipping off,- feeling of the sash with his eye-lashes, and flattening his nose on the glass. Great drops splashed and splattered down the panes; little puddles stood on the sill; the trees blew about; the road was wet, and the mud was deep.

" Come, Trotty," said Lill.

" Yes," said Trotty.

" Come, Trotty," said his mother, five minutes later.

" Yes 'um," said Trotty; but he did not move.

" He 's watching for Mr. Hymnal," exclaimed Lill ; " it is late for him ; I wonder where he is."

Mr. Hymnal was going to preach that day; he drove over from East Bampton on an exchange; he was to dine with Trotty's mother, and Trotty felt burdened with the entire responsibility of him.

*' I declare ! " exclaimed his mother, at the end of another five minutes. " There 's the bell this moment, and Trotty must have his jacket changed, and his boots blacked, and his hair brushed, and his coat sponged. I sent him to wash his hands just three quarters of an hour ago. Has n't touched them ? I presume not. Nor found that blue ribbon yet, either, have you, Trotty ? The little blue bow, you know, grandmamma, that he wears at his throat. He sewed it all into a knot with black linen thread yesterday, and harnessed the cat into it the day before ; the last I saw of it, he had hung Jerusalem by it on the banisters, and-Trotty! Trotty! Leave that window now, and come right here to me ! "

" I s'pose if he should n't come, I 'd have to preach myself," observed Trotty, with a thoughtful-sigh, as Lill pulled him up stairs by the curls, - that little arrangement, by the way, was Lill's forlorn hope in her management of Trotty. To command, persuasion, and entreaty he had a dignified habit of paying just no attention at all. Should she lead him by one hand, he was skilled in pinching her with the other. Did she imprison both his little round wrists, you may believe that he knew how to kick ! She might carry him in her arms, but he understood perfectly how to lift up his voice and weep in such an effective manner that the united family flocked to the spot to see " What Lill was teasing Trotty about now." But when she once had a firm hold of those curls, - it was like taking a handful of sunbeams, - Trotty was outgeneralled. Wherever Lill went, there lie could not conveniently refuse to follow. Sometimes, indeed, he preferred having his hair nearly pulled out by the roots, to yielding the field, and then, Lill being too gentle really to hurt him, the case was hopeless. On one occasion he contrived to make a timely use of the scissors, and clip off a large front curl, and Lill walked on with it for some time before she found out that he was n't behind it.

Trotty was brushed and washed and dusted and tied and buttoned and pinned at last ; mamma was ready, and Lill, and Max ; the bell rang and the bell tolled, but Mr. Hymnal did not come.

" It must be the mud and hard driving that have delayed him," said mamma. "Very likely he will stop at the church without coming to the house ; we won't wait any longer, I think."

Trotty began to look sober. When they came in sight of the church, he bobbed out from under Lill's umbrella and ran through the rain to his mother.

" Mamma, if the minister does n't come, may I preach ? "

" O yes," said Mrs. Tyrol, laughing at what she thought was some of " Trotty's fun." " You may preach," - and thought no more of what she said.

Mr. Hymnal's horse was not in the sheds; Mr. Hymnal was not in the pulpit. Trotty sat down in the tall box-pew and thought about it.

"I want the corner," said he to Max mysteriously, and Max, to please him, lifted him into the corner. The church was nearly full; the people began to grow still; the pulpit was yet empty. A door opened somewhere; Trotty kneeled on top of some hymn-books, and, turning around, looked attentively over the house. The blind organist had just come into the gallery, and was groping his way along with his cane, which made little taps on the floor. Trotty sat down again. In a minute another door opened, and a pew door flapped. Up went Trotty's curls and eyes again, where all the audience could see. It was old Mrs. Holt that time, -- Mrs. Holt who was always late, and who wore the three-cornered green glasses, and walked like a horse going up hill. She tripped over a cricket as she went into her pew, and Trotty's curles and eyes laughed out ; he never could help laughing at Mrs. Holt, -- the people saw him turn as pink as a rosebud, and disappear under Max's arm. He felt so ashamed! Presently a door opened again, and some very new boots creaked very loudly up the whole length of the broad aisle. Everybody thought that they were the minister's boots, and so did he. But it was only an old deacon in a black satin stock ; he sat down slowly, slowly buttoned his pew door, slowly sunk his chin into his stock, and slowly and severely coughed; a sort of slow astonishment that everybody should be looking at him crept into his wrinkles and his eyebrows. He concluded that he must have put his wig on crookedly, and in feeling around to find out he pulled it off.

But nobody else came in after that; the empty pulpit stared down at the people; the people stared up a tthe empty pulpit. Silence fell, deepened, grew painful, grew awful, grew funny. Two small boys in the gallery smiled audibly. The old ladies put their handkerchiefs to their mouths. The Deacon in the wig looked at another Deacon ; another Deacon looked at them both ; a fouth Deacon beckoned to the third Deacon ; then all the Deacons whispered solemnly.

What was going to happen next?

Trotty had been sitting very still.

His mother, as it chanced, had her hand over her eyes just then. Max was -- well, to tell the truth, Max was too busy in wishing that the veil on Nat's pretty sister's pretty hat did not fall so far over her face to notice much of anything else.

Suddnly they heard a stir. A choked laugh ran from slip to slip. Everybody was looking into the broad aisle, and -- Dear me! where was Trotty?

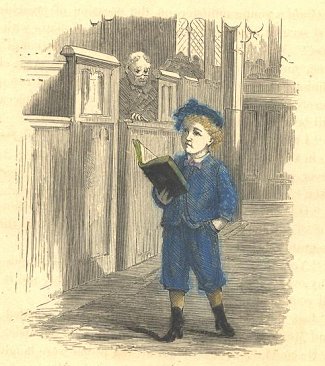

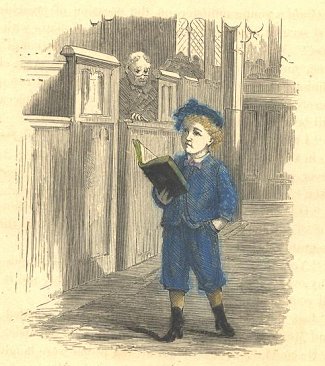

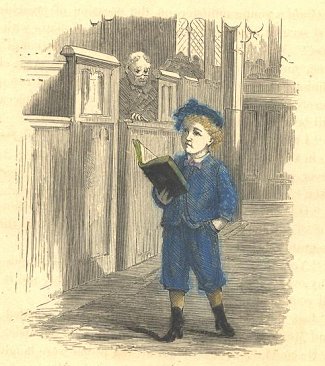

Out in the middle of the great empty aisle, with one hand stuck jauntily in the pocket of his little Zouave trousers, and a huge hymn-book in the other, with his cap on back side in front, ribbons and curls tossed into his eyes, dimple smoothed severely away, and a ministerial gravity on his pink chin, stood Trotty.

Before they knew what he was about, he was on the platform. Before they could reach him, he had begun to climb the pulpit stairs.

Just at that point he felt Max's hand upon his collar, and the next he knew he was securely buttoned into the pew again, at a safe distance from the door.

Could a young minister, on the occasion of preaching his first sermon, bear such a surprising turn of affairs with calmness ? Was it not enough to quench the ambition of a lifetime, and ruffle the patience of the saints ? Any clerical opinion on this point, if forwarded to the address of the Reverend Mr. Trotty, in my care, - or to me, in his care, - will be thankfully received, and duly appreciated.

" I was a goin' to preach," said Trotty, quite aloud, standing up in the pew, and squaring at Max with both fists. " You never pulled Mr. Hymnal round that way, you. know you didn't ! Now, I should like to know why you-"

" O hush, Trotty ! hush! " His mother drew him down out of people's sight, but he turned on her with the quiet assurance of victory : -

" You said I might preach! You said I might, on ve [sic] way over ! Now we have n't got any minister, and it's just all your fault ! "

Just then there was a noise at the green, muffled doors, and Mr. Hymnal came walking very fast up the aisle.

He could not imagine what all the people were laughing at.

He wondered so much, that he read the Missionary Hymn in this way, -

" From Greenland's icy mountains,

From India's coral strand,

Where Afric's soda fountains

Roll down their golden sand."

But somebody says I should not tell you how he read it, for fear that you may laugh the next time you hear it in church.

Under the circumstances, Mrs. Tyrol thought that Trotty had better stay at home that afternoon.

Feeling quite insulted, but a little too proud to say so, Trotty watched the rest walking off to the music of the ringing bells, and then sat down with [his doll] Jerusalem to watch the rain. He amused himself for a while by counting the little dreary drops that rolled down the glass and melted away into the wet sill, but by and by that began to be dull work, and he told Jerusalem that he thought they had better go to church; he had a very good sermon, which he should have preached this morning if it had n't been for that old Max; if Jerusalem would be a good boy and not knock the hymn-books down, nor cry for candy, he might hear it now. Jerusalem bowed his empty head, - nothing came more naturally to Jerusalem than making bows, - so Trotty tied him into the high-chair, and himself mounted the dining-room table, with a sofa-cushion, a Bible, and Mother Goose, to preach.

That table made an excellent pulpit,-when mamma was n't there to take yon down ! - and Jerusalem was as quiet and attentive an audience as a clergyman could ask for. Biddy was in the kitchen, and would have been glad of an invitation, but Biddy had a way of laughing in church which was very disagreeable. Trotty thought that she could not have been taught, when she was a little girl, to pay good attention to the sermon.

So Trotty preached to Jerusalem, and Jerusalem listened to Trotty, half through the dark, wet, windy afternoon. I am sorry not to have a phonographic report of that sermon, but Jerusalem, who gave me the account of it, gave it from memory only, so that I fear a large part of the minister's valuable thoughts are lost. A few have been preserved in fragments, as follows: -

" My text will be found in the first chapter of Methuselah: I love vem vat love me, and vose vat seek me early sha' n't find me,'-sit still, Jerusalem!-Moses was a very good man. 'Lijah went up in a shariot of fire. I b'lieve I saw him one time last summer when there was a thunder-storm. - Jerusalem! don't drum on 'e hymn-books in meeting time. - Once when I had a white kitty she died and went to heaven. I know 'most she went to heaven, 'cause she was so white, and she never scratched me but once. I don't like dogs, not big black ones. They bark. I don't like the dark either. Samuel was afraid of the dark. So 'm I. Now I lay me - you can't say, Now I lay me, Jerusalem !- Schildren, obey your parents, and unite in singing the 'leventh psalm : John Brown's Body, old metre : Amen."

Before the singing was over, the little minister espied a saucer of parched corn on the sideboard, and the idea struck him, what a nice stuffing it would make for Jerusalem's head. So, after telling the choir to keep right on, he climbed down from the pulpit, and began to drop the corns, one by one, into the doll's silk skull. This was great fun. When it was filled to the top, Jerusalem found that he could hold his head up as straight and stiff as other people. In fact, he might to this day have been able to look the world in the eye, if it had not been for the little circumstance, that, one by one, those corns mysteriously disappeared. Where they went to Jerusalem has never revealed; but the truth remains unquestioned, that before Mr. Trotty's sermon was over, that poor head hung despondent and empty. As for the saucer on the sideboard that was empty too.

When the real people came home from the real church, they found the Reverend Mr. Trotty drawing his audience noisily all over the house in a tip-cart.

" O, I'm sorry," said mamma, laying her gentle hand on his shoulder. " We don't play with tip-carts on God's Sunday. '

" Well," said Trotty, after some thought ; " you see I 'in a little boy, and don't know any better! "

" I think we'll have a little catechism after that," thought mamma.

So when she had put away her things she took him up in her lap, and began the only catechism that Trotty knew,-it was one of his own making.

" Trotty, what did the wicked man do to President Lincoln ? "

" Shooted him."

" What did we do when we heard about it ? "

" Cried."

" Where did President Lincoln go ? "

" Up to heaven."

" Will Trotty go, if he is a good boy ? "

" O yes."

" What did the wicked men do to the poor black people ? "

" Shut 'em up."

" What did President Lincoln do ? "

" Let 'em out."

" Trotty," rather softly, " who else has gone to heaven ? "

" Papa."

" What will he do when he sees his little boy ? "

" Come runnin' right out to meet me."

" What else ? "

" Kiss me."

" Who is building a little home for Trotty in heaven ? "

" The Lord Jesus Christ, mamma."

" What would my little boy say to the Lord Jesus Christ ? "

" O, I 'd let Him kiss me."

" What else ? "

" I 'd shake hands to Him."

" Anything more ? "

" I 'd send my love to Him ! "

That night they let Trotty sit up half an hour later than he ever had done before. Grandmother said that she thought he was old enough to stay to prayers on Sabbath nights and hear the singing.

So Trotty stayed, and when they were singing the " Battle Hymn of the Republic," he joined in on a shrill tenor, with

" Hang Jeff Davis " ; when they attempted " Maitland," he struck up each line just as the rest had finished it; when nobody was looking, he gave himself the pleasure of a little practice with both fists on the bass keys, and when they scolded him for it, he crept under the piano and sat down on the pedals. Altogether he enjoyed the evening very much.

" Why don't you sing that one 'bout going to heaven in a steamboat?" he asked several times.

" Going to heaven in a steamboat ? " Nobody could guess what he meant.

" O, I know," said Lill at last. " He means ' Homeward Bound.' "

They played " Homeward Bound " to please him, and he sang,

" Stiddy ! O Pilot! Stand firm at the wheel! "

with his mouth very wide open, and dancing up and down hard all the time on Max's corns.

After the singing everybody repeated a hymn or a Bible verse. Trotty listened with bright eyes. His turn came last. They all wondered what he would say.

" Come, Trotty," said mamma. Trotty stood up with his hands in his pockets, and slowly and solemnly said: -

" I had a little hobby-horse,

His name was Dapple Gray,

His head was made of peel-straw,

His tail was made of bay."

O, how they all laughed !

" I don't see what 's the matter with me," said Trotty, almost ready to cry. " Besides, if Lill knew how ugly she looks a laughin' she 'd stop."

" That was n't exactly a hymn, you know," said his mother, trying to be sober. " You come and stand by me, and say ' Dear Jesus,' and let Lill see how well you know it."

And it was so pretty to hear him that I think I must copy the words just as he pronounced them.

" Dear Zhesus ever at my side,

How loving you must be,

To leave vy home in heaven to guide

A little shild like me.

" I cannot feel ve touch my hand

Wiv pwessure light and mild,

To sheck me as my mover does

Her little wayward shild.

" But I have felt ve in my foughts

Rebukin' sin for me,

And when my heart loves God, I know

Ve sweetness is from ve.

" And when, dear Saviour, I kneel down

Mornin' and night to prayer,

Sumfin vere is wivin my heart,

Vat tells me Vou art vere."

Back to main page

NE Sunday it rained. Not that it never rained on any other of Trotty's Sundays, but that it did rain that especial Sunday.

NE Sunday it rained. Not that it never rained on any other of Trotty's Sundays, but that it did rain that especial Sunday.