Like many of the 19th-century women who wrote series for children, Katherine Kent Child Walker (Mrs. Edward Ashley Walker) came from a religious background. And, like several of her counterparts, she drew on her own life for some of her publications, especially after her marriage. In contrast with many married series authors, however, Walker wrote her juvenile series when she was single. After her marriage, most of her publications were in periodicals. Whether writing articles for adults or relating anecdotes about her daughter for children's magazines, Walker often adopted a light-hearted tone, and her best-known piece is the humorous "The Total Depravity of Inanimate Things" (1864).

Katherine Kent Child was born February 8, 1833, in Pittsford, Vermont. Her father, Rev. Willard Child (1796-1877), was a graduate of Yale College and Andover Seminary (locations that would be mentioned in Walker's fiction). Her mother, Katherine Griswold Kent (1805-1851), was born in Benson, Vermont, and was also the daughter of a minister (Dan Kent). [1] Katherine's birthplace was Rev. Child's first parish, and he and his wife remained there long enough to have five children (Katherine was the third) and to bury three of them in infancy or early childhood.

Katherine thus grew up with one older brother, Willard Augustus (1828-78), who would later become a doctor, perhaps with the knowledge that another brother, Cephas (1830-31) had died eighteen months before she was born, and with childhood memories of her other siblings' deaths. Her sister Fannie F. (1838-43) was born when she was five; her brother Charles H. (1840-43), when she was seven. They died within two weeks of each other when Katherine was ten. Three years later, another sister, Emma Juliette (1846-47), was born -- but lived only eighteen months. This pattern was, perhaps, a tragic foreshadowing of Katherine's future life, for she was destined to outlive all of her family.

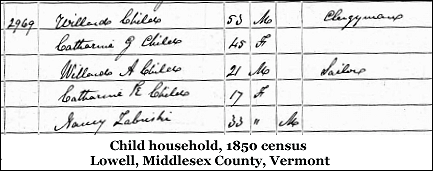

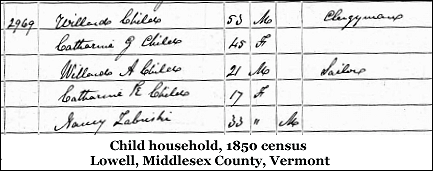

The family also weathered several moves during Katherine's childhood: in 1842, Rev. Child served in Norwich, and in 1845, in Lowell. The 1850 census shows the four surviving Childs at home together in Lowell, with Katherine's brother listed as a sailor, and her father as a clergyman. The following year, the family suffered another loss -- Katherine's mother. Four years later, on February 14, 1855, Rev. Child was installed as pastor of the Congregational church in Castleton, Vermont, where he would remain for the next nine years. During most of that time, Katherine appears to have lived with him.

Katherine Kent Child's first two books, A Little Leaven, and What It Wrought at Mrs. Blake's School and Our Little Girls, [2] were published in 1858 by Anson D. F. Randolph, a firm that specialized in religious juveniles. Leaven appears to have some autobiographical elements: the protagonist is a minister's daughter, the family's surname is Griswold (her maternal grandmother's surname), and the school appears to be located near or in New Haven ("Quinnipiac").

Both books were issued anonymously: A Little Leaven was credited to "the author of [the as yet unpublished] 'Our Little Girls'"; Our Little Girls, to "the author of 'A Little Leaven.'" Given this history, it's possible Child was also contributing unsigned articles to magazines or newspapers during this period, though none have been identified. She is, however, listed with the occupation "authoress" in the 1860 census -- an apt designation, for Watson's Woods; or, Margaret Huntington's Experiment, the sequel to A Little Leaven, was published in 1859, and The Two Heaps and What Miss Brown's Sunday-School Class Did about Them in 1860.

The 1860 census records "Kate K. Child" and her father in Castleton, Rutland County, Vermont. They were living with 61-year-old Chester Spencer, an express agent; his 60-year-old wife Elizabeth; 32-year-old George Spencer, a merchant; and three servants. Whether the Childs were boarding with the Spencers or had a family connection is unclear. The spaces in the census record for "Value of Real Estate" and "Value of Personal Property" are blank for both Childs, suggesting a limited income. Comments by Katherine in Leaven and "The Depravity of Inanimate Things" allude to the financial constraints found in ministers' households.

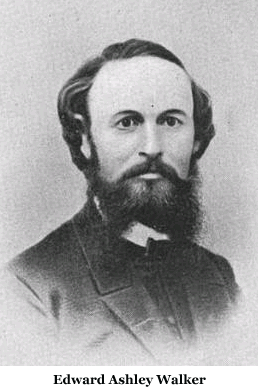

The Childs' situation contrasts with that of Katie's future in-laws. The Walkers appear in the 1860 census in New Haven: her future father-in-law, Alfred Walker, is a merchant with $33,000 in real estate and another $20,000 in personal property. The family includes Eunice (Alfred's wife); her future husband, Edward Ashley, age 25, listed as a Congregational clergyman; his younger siblings, 18-year-old Alfred and 16-year-old Fanny; and two servants. Edward had barely returned to the United States in time to be listed in the census, having spent the previous two years studying abroad in Paris, Berlin, and Heidelberg.

When and how the couple met are unknown. In 1861, the American Tract Society published The Cross-Bearer: A Vision, a collection of Child's poems supplemented with "other poetical selections and sketches in prose" selected by the editor, Rev. Kirk. Katie's preface (dated October 1861) mentions that the work was inspired by "seven pictures (French in origin)" which she had received "some months ago . . . through the kindness of a friend," which raises the slim possibility that Edward's time in France may have had some connection with those illustrations.

As with Katherine's earlier work, The Cross-Bearer was published anonymously. Her next known publication, from 1862, appeared under the pseudonym K. K. Kind, and marks her transition into writing about her own experiences for adult periodicals. "St. Luke's Hospital," her first known piece for Harper's, describes her visit to the children's ward of the New York City hospital in the company of an unidentified doctor (possibly her brother).

Edward, too, was starting to publish religious material, but of a different tenor: his 30-page "The Present Attitude of the Church toward Critical and Scientific Inquiry" appeared in the April 1861 issue of The New Englander, and his much longer essay, "The First Document of Genesis: A Review of C. W. Goodwin's Essay on the Mosaic Cosmogony" ran in the July issue.

Edward was ordained in June 1861, in New Haven. He had enlisted in May and thereafter served as a chaplain for the Connecticut Volunteers 1st Regiment Heavy Artillery, concluding his time in the military in July 1862. In November, he published Our First Year of Army Life: An Anniversary Address, Delivered to the First Regiment of Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery, at Their Camp near Gaines' Mills, Va., June, 1862, recording his memories of his time with the regiment. The preface noted that publication had been delayed by illness, and other accounts of Edward's life attribute that illness to conditions he encountered while serving.

Katie (as she was called) and Edward were married in Castleton, Vermont, on March 25, 1863, with her father performing the ceremony. The next day, her brother Willard, now an M.D. (and serving as an army surgeon), married his sweetheart, Emma M. Knapp, in Mooers, New York -- with Rev. Child again officiating. [3] Katie also had two more children's books, Zoe's Story; or, Old Friends and Foes in Masks and Pet Dayton, published in 1863, both again anonymously and by A. D. F. Randolph.

For a brief time, all went well. Several months after the marriage, Edward accepted a parish at the First Congregational Church in Worcester, Massachusetts, and was installed on July 2, 1863. Once again, Katie's father performed the ceremony. The couple's only child, Ethel Childe Walker, was born on February 24 or 25, 1864. Katie had submitted several more pieces to Harper's and her most famous article, The Total Depravity of Inanimate Things, was published in the Atlantic Monthly that September. The article, a butter-side-down piece, contains a number of anecdotes, including the following long one relating her own experience with a limited dress budget:

So also every wielder of the needle is familiar with the propensity of the several parts of a garment in the process of manufacture to turn themselves wrong side out, and down side up; and the same viciousness cleaves like leprosy to the completed garment so long as a thread remains.

My blood still tingles with a horrible memory illustrative of this truth.

Dressing hurriedly and in darkness for a concert one evening, I appealed to the Dominie, as we passed under the hall-lamp, for a toilet-inspection.

"How do I look, father?"

After a sweeping glance came the candid statement,-

"Beau-tifully!"

Oh, the blessed glamor which invests a child whose father views her "with a critic's eye"!

"Yes, of course; but look carefully, please; how is my dress?"

Another examination of apparently severest scrutiny.

"All right, dear! That 's the new cloak, is it? Never saw you look better. Come, we shall be late."

Confidingly I went to the hall; confidingly I entered; since the concert-room was crowded with rapt listeners to the Fifth Symphony, I, gingerly, but still confidingly, followed the author of my days, and the critic of my toilet, to the very uppermost seat, which I entered, barely nodding to my finically fastidious friend, Guy Livingston, who was seated near us with a stylish-looking stranger, who bent eyebrows and glass upon me superciliously.

Seated, the Dominie was at once lifted into the midst of the massive harmonies of the Adagio; I lingered outside a moment, in order to settle my garments and--that woman's look. What! was that a partially suppressed titter near me? Ah! she has no soul for music! How such ill-timed merriment will jar upon my friend's exquisite sensibilities!

Shade of Beethoven! A hybrid cough and laugh, smothered decorously, but still recognizable, from the courtly Guy himself! What can it mean?

In my perturbation, my eyes fell and rested upon the sack, whose newness and glorifying effect had been already noticed by my lynx-eyed parent.

I here pause to remark that I had intended to request the compositor to "set up" the coming sentence in explosive capitals, by way of emphasis, but forbear, realizing that it already staggers under the weight of its own significance.

That sack was wrong side out!

Stern necessity, proverbially known as "the mother of invention" and practically the stepmother of ministers' daughters, had made me eke out the silken facings of the front with cambric linings for the back and sleeves. Accordingly, in the full blaze of the concert-room, there sat I, "accoutred as I was," in motley attire, - my homely little economies patent to admiring spectators: on either shoulder, budding wings composed of unequal parts of sarcenet-cambric and cotton-batting; and in my heart -- parricide I had almost said, but it was rather the more filial sentiment of desire to operate for cataract upon my father's eyes. But a moment's reflection sufficed to transfer my indignation to its proper object, -- the sinful sack itself, which, concerting with its kindred darkness, had planned this cruel assault upon my innocent pride.

By the time "Total Depravity" appeared, however, Katherine's life may not have been as light-hearted as her tone in the article suggests. Edward's health was still poor, and his time in the Worcester parish was short. One biography notes that he "spent the winter of 1864-1865 in Southern Europe, hoping to restore his health," but found himself "still too feeble for active duty." [4]

Katherine traveled with him to Europe, chronicling their journeys in several articles for Harper's, most published under the name Katherine C. Walker: "A Nice Time" [Nice, France], "Seeing Naples," "Pozzuoli and Vesuvius," and "All Roads Lead to Rome" appeared from August 1865 through January 1866; additional articles based on their time in Rome ran in summer 1866.

It may have been while traveling abroad that the Walkers discovered a work by Franz Hoffman that they thought suitable for an American audience, for in 1865 A. D. F. Randolph published Katherine's translation of Climbing the Glacier, another work for children.

At some point in 1865 -- probably May -- the Walkers returned to the United States. They may have spent the next few months in New Haven, but Edward's health was still poor and he officially resigned his position in Worcester in September 1865. From there, they moved to Marquette, Michigan, where he died April 10, 1866.

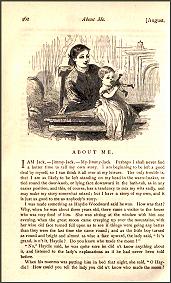

Katherine continued to write. She had begun sending material to the children's periodical Our Young Folks in 1866, and, in 1867 and 1868, published a series of stories that were essentially accounts of her daughter Ethel's activities. "About Me," from August 1867, was ostensibly about a toy given to Ethel,  and describes the baby's time with her grandparents (Edward's parents) "because her own papa and mamma had been forced to leave her behind while they went over the seas in search of a blessing which they were not to find"; it includes excerpts from family letters and a description of Ethel's reunion with her parents. "About Me and the Big Sea Water," from May 1868, covers the family's time in Michigan -- presumably their last Christmas together before Edward's death, though the article maintains a lighthearted tone. [5] "About Me on My Travels," from July 1868, describes a trip to visit (unidentified) relatives.

and describes the baby's time with her grandparents (Edward's parents) "because her own papa and mamma had been forced to leave her behind while they went over the seas in search of a blessing which they were not to find"; it includes excerpts from family letters and a description of Ethel's reunion with her parents. "About Me and the Big Sea Water," from May 1868, covers the family's time in Michigan -- presumably their last Christmas together before Edward's death, though the article maintains a lighthearted tone. [5] "About Me on My Travels," from July 1868, describes a trip to visit (unidentified) relatives.

Walker also sent occasional articles to The Advance in late 1867 and early 1868; by mid-1868, her short pieces were appearing semi-monthly or monthly on its first page. Again, some drew on her travels or home life ("The Dead of Rome," parts I and II, and "Not about the Dead of Rome" -- the latter, a humorous account of trying to write another piece, with an active child playing outside and calling for attention).

1869 saw a more unusual project -- two works for children, each in one-syllable words, both published by the New York firm of George A. Leavitt. From the Crib to the Cross was, as the subtitle explained, A Life of Christ in Words of One Syllable (except for proper names). The other was one of several attempts by various authors to retell Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress for children. Both received largely favorable reviews. One of the few dissenters was The Universalist (a periodical associated with the era's most lauded attempt to assess the quality and content of books for Sunday School use, and thus staffed with reviewers conversant with the genre), which rightly pointed out that in some cases longer words would have better served the purpose and been more familiar to the readers. Or, as the reviewer put it:

Both the thought and the clearness of expression are sometimes sacrificed . . . What advantage, for instance, has "priest" over "minister," and "fiend" over "demon"? To miss such words as "spirit," "heaven," "angel," "mother," "father," "children," "Bible," in a book which professes to give the story of Jesus, is almost to miss the whole fragrance of the narrative. [6]

Even that review,  however, while also acknowledging doctrinal differences with the texts, concluded, "These volumes are so beautiful and in many respects so admirable, that we find the greater regret that we are unable to commend them unqualifiedly."

however, while also acknowledging doctrinal differences with the texts, concluded, "These volumes are so beautiful and in many respects so admirable, that we find the greater regret that we are unable to commend them unqualifiedly."

By 1870 -- probably several years earlier -- Katherine and Ethel had moved to Crown Point, New York. The 1870 census shows them sharing a home with her 74-year-old father. Her brother Willard and his family were in Mooers, about eighty miles north.

Walker also continued to send the occasional article to The Advance and, in 1870, to Christian Union as well. She appears to have been writing fewer pieces for children, but did pen an occasional item, such as "Little Noble's Sermon" for Hearth and Home. Several articles from 1871 and 1872 suggest she was also working with children either in Sunday Schools or on philanthropic projects: "The Willing Hearts" in the December 1872 issue of the mission magazine Life and Light for Heathen Women describes one such organization.

During the mid-1870s, Walker sent most of her material to several different periodicals -- religious and autobiographical fare to Illustrated Christian Weekly and Christial Union, an occasional juvenile to Youth's Companion or Oliver Optic's Magazine, and one or two items to Scribner's or Atlantic Monthly.

More changes to the family and household occurred near the end of the decade. Katherine's father died in November 1877, the day before what would have been his 81st birthday. Three months later, her brother died. At some point prior to the 1880 census, Katherine and her daughter Ethel moved to New Haven. The 1880 census includes Katherine as part of her in-laws' household, living with her father-in-law and mother-in-law, her sister-in-law Frances (presumably the "Aunt Fanny" mentioned in several of her stories), Ethel, and two other relatives -- Mary A, another widowed daughter-in-law, and Alfred E, probably Mary's child. Katherine and Ethel may have been in New Haven because of the Yale Art School, for Ethel enrolled there about 1880 or 1881.

1880 saw two of Katherine's articles published in the Atlantic Monthly, "The Bible in the Nursery" and "Some Intimations of Early Childhood." She also published several pieces in Sunday Afternoon during this period. After 1880, her publications either dropped sharply or have not been located: only two items, one from 1882 and one from 1899, have been identified.

In February 1885, Walker suffered another tragic loss. While at school, Ethel caught a cold which turned to pneumonia, and she died the morning of February 13. A special service was held the following week. Katherine arranged for a memorial booklet comprised of the services and letters of condolence to be published; its frontispiece was a drawing by Ethel found in her portfolio. Katherine also donated $200 to the Yale Art School to establish the Ethel Childe Walker Prize "for deserving pupils"; the award is still given to an outstanding art student.

Katherine appears to have remained with her in-laws for several years after Ethel's death. She is with them in the New Haven City Directory in 1888; about 1889, she begins boarding with Miss Susan E. Daggett and Miss Mary Daggett, at 77 Grove. A notice in the November 14, 1899, New Haven Register refers to a reception that "Mrs. Edward A. Walker and the Missess Daggett" held "at their home" at that address (with the house "most beautifully decorated for the occasion with palms and cut flowers, many of which were the gifts of the guests"). Katherine's exact relationship to the Daggetts is unknown, though Walker and Susan Daggett were both members of the same church (Center Church). Susan Daggett was also involved in religious and philanthropic activities, [7] in which Katherine may have participated. Katherine remained at Grove Street at least through 1913, as did Susan Daggett.

Katherine Kent Child Walker died November 17, 1916. Among her final bequests were two to Yale: $500 to the School of Fine Arts, in memory of her daughter, the income to be used for library books; $1220 for the Katherine K. Walker Prize, its income to be awarded to a student "judged by competent authority to have promoted, by deed or by creditable writing on the subject, that patriotism to which Chaplain Edward Ashley Walker, of the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery, devoted his young life in willing sacrifice." [8] She is buried in Grove Street Cemetery, New Haven, Connecticut, with her husband and daughter. [9]

Content notes only; additional information on sources for Walker's biography provided on request.

1. A biography of Rev. Dan Kent, transcribed from "The Kent family history, a family genealogy," and a family tree are at his Find a Grave entry. See also Loyal C. Kellogg, "Benson," Vermont Historical Gazetteer, vol. 3 (Claremont, NH: Claremont Manufacturing, 1877): 410-11, Google Books.

2. See "Katherine Kent Child Walker -- Publications Checklist" for a chronological list of Walker's publications and links to online versions of the texts.

3. Several dates have been seen for the two marriages; those used are from the 1 April 1863 New Haven Daily Palladium and the 5 May 1863 Vermont Chronicle. Both of those sources give March 25 and March 26 for the services.

See "John Gibson Collection," Vermont in the Civil War (online) for a photograph of Katherine's brother Willard and a summary of his service record. Katherine's 1864 magazine article "One of the 'Dogs of War'" from Scribner's also talks about him -- and a "dog of war."

4. History of the Academic Class of 1856, Yale University, to 1896. (Boston, 1897): 183-84. This work is also the source of the photograph of Edward Ashley Walker.

5. Although the narrator usually refers to the

child as "Queenie," in "About Me and the Big Sea Water," after Queenie has referred to "Uncle Willy" (Katherine's brother) and "Aunt Fanny" (Edward's sister), the narrator mentions that "Queenie's real name was Ethel" (284).

6. "Literary," The Universalist, November 27, 1869, msg. pg. The next quote is also from this source.

7. A detailed biography of Susan Daggett reprinted from The Quilt Digest is online at "Old Maid, New Woman," Shelly Zegart Quilts, Inc. See also the description of the Oliver Ellsworth Daggett Scholarship Prize at Yale University's Divinity School, which suggests that, like Katherine, Susan had ties to Yale.

Internet Archive's A History of the Doggett-Daggett Family (1894) includes brief mention of Susan and a biography of her father Oliver Ellsworth Daggett.

8. Report of the Treasurer of Yale University (New Haven: Yale, 1920): 255.

9. See

Katherine Kent Childe [sic] Walker, Find a Grave, for a photograph of the gravestone.