by Virginia F. Townsend

Paul Hines stopped suddenly and drew his breath hard. It was the sight of that little girl's face before the great toiling loom, with the bright cotton threads of scarlet and black dancing around, which made the boy -- at fourteen he really was no more -- forget everything else for the moment.

Perhaps you would have thought it a pretty face, perhaps not. It did not show to good advantage certainly in that dress of faded blue alpaca, with the soiled cotton lace about the neck. It was clouded with weariness after the long morning's work, and the delicate temples were a little grimed with the dust which had settled among them.

Paul Hines, at least, never once thought of its prettiness, yet that little pale face, under its cropped brown hair, with its eyes just the blue shade of a May sky at noon, had a meaning and charm for him which probably no other face in the world would have possessed.

It brought up another face to Paul Hines. The roses of that very June were blossoming over its sleep. it had sparkled and dimpled all about his young boyhood. It had faded into the dark and silence only the year before. There was a difference between the two faces. This one might stand for a portrait, pale and unfinished, of Paul's sister. In her cheeks the rose-pink bloomed steadily; in these it hovered faintly. There was no cloud in Edith Hines' blue eyes, no patient weariness about her little dimpled mouth. She was a flower that soft rains and tender sunshine had nursed into fairest bloom. This one was like a half wilted lily, with no rich soil at the roots and only gray skies over it; yet, for all, how like the two were -- how wonderfully like!

All around them was the deafening noise of the machinery, the whirl of the great wheels steady and relentless as fate, the jarring overhead, the rumbling underfoot; the close, hot air, the greasy smells of oils and dyes, and the lines of blank, tired faces at the looms -- faces of spinners and weavers, young women, middle-aged, and sometimes an old face and sometimes a child's.

It made one's heart ache to think of the contrast of the June day outside, all alive with sunshine, the cool green meadows starred with daisies, the orchards with their pink clouds of bloom, the sweet-throated robins and orioles brimful of song, and the blue, clear air through which floated the breath of wile roses, the languid scent of the lilacs, the faint sweetness of the apple-blossoms.

All this was outside, while inside the walls of the vast cotton factory was the steady roar of the machinery, the rush of the wheels, the clouds of dust, and the endless toil.

The eyes of Paul Hines met those of the tired little spinner as she looked up from her cotton threads. She saw that he was standing quite still, staring at her, while the rest of his party went on laughing and chatting so gayly that you could hear their voices over the roar of the wheels.

A faint flush came into the sallow cheeks as the girl's gaze met the spirited face, the dark, handsome eyes bent on her.

Paul saw that. It made him long to bring some fresh light into those blue, weary-looking eyes, and a smile (with a little dimple just outside of it) about the pale, silent mouth, so he drew near to the small spinner, and asked, in the kindest possible manner:

"Won't you tell me your name?"

The answer came promptly enough, though a shy, startled look accompanied it:

"Elsie Palmer."

Elsie and Edith! Each of the pretty names seemed to match the other, Paul thought.

He went on:

"How many hours do you work here?"

"From seven in the morning until twelve; then we have an hour for rest and dinner; and then we work again until six."

"Is the work very hard?"

The girl drew a long, long breath.

"Not very hard," she said: "only it seems as though six o'clock was a long while coming most days."

Elsie Palmer did not know that the weary waiting for the factory-bell -- the slow pain at her heart -- the tired ache through all her poor little limbs, while her strained ears listened and hungered for the welcome peal -- had crept into her voice. She did not know it; but Paul had heard all that in her tones, and it touched his heart.

"How long have you worked here?" he asked, wondering within himself what possessed him, and how much longer he would stand here questioning the little spinner.

"I came in March" she said. "It was very soon after my mother died. Edith's mother had died, too; but she never had to go into a factory to work, thank Heaven!" [sic]

Paul had never thanked Heaven for that, before.

"And who takes care of you now?"

The next moment Paul felt as though he could have bitten his tongue out for asking that question, when he saw the sudden quiver on the girl's lip. But it grew still in a moment, and then she answered in the same grave, quiet voice, lacking somehow in the spring and hope of a child's tones:

"I board with the factory girls now. Some of them are kind to me."

Paul broke out then. He was an outspoken, hot-tempered boy, not apt to remember that discretion is sometimes the better part of valor.

"It is a burning shame to shut up such a mite of a girl as you all day in a dark old factory, and keep her at work like a slave! You ought to be out this very minute, running in the grass, and having a good time, with the sunshine, and birds and flowers. If I could have my way you'd be hustled out of this old prison double-quick!"

At that speech a sudden light of surprise and pleasure broke into the girl's blue eyes, the pale cheeks flushed the rosiest pink, and a smile, half arch, half pathetic, came about the mouth.

"I wish you could have your way, oh, I wish it very much!" said Elsie Palmer.

At that moment Paul heard voices calling him. There was no more time to spare. Yet he went off reluctantly to join his party, and the light talk, and the merry jests while they were passing from one room to another in the great building jarred on Paul Hines' soul. The face of the tired little spinner before her loom, with the bright cotton threads whirling around her, haunted the boy. There was a dreadful pathos in it, doubly dreadful to Paul because of the resemblance to that other face, lying under the fresh grass and the fragrant roses of that June morning. But Paul thought he would rather it should lie there, sweet and still, forever, than be doomed to pass ten hours of each day in the darkness of that old factory, with the deafening noise, the sickening heat, and the endless rush of the great wheels.

But Paul Hines was a boy of fourteen, full of elastic spirits, of joyous health, of bright, eager life, his mind too was at this time full of one all absorbing topic, for he was to sail for Europe the next week with the son of an old friend of his father, and the boys were to spend the next two years in a German university. Paul's young companion had been very ill, and the doctors had sent him abroad to regain his health, and as the two had been playmates from their infancy it had been settled that they should go together.

"A boy who had brains could keep up his studies on one side of the sea as well as another," Paul's guardian had said when the matter of his going abroad at this juncture had been under discussion.

With so much on hand to engross his thoughts it is probable that the boy would soon have forgotten the incident of the morning, and the face of the little cotton-spinner would have faded out of his remembrance had not a fresh incident occurred to engrave it on his memory.

The great bells suddenly rung the hour of noon. In an instant, as though by magic, the huge machinery, the revolving wheels, the flashing pulleys, the great iron arms, strong and tireless as those of Hercules, stood still. The huge monster of the mill, with its three hundred hands, stopped to take breath as the sun touched the zenith.

At that moment the party of visitors had commenced the descent of the fifth story. Paul's uncle, who was one of the principal mill-owners, had been resolved that his guests should see the building thoroughly, and especially the new machines they had just put in on the upper floor and that were a miracle of power and innovative skill.

On the third flight Paul came suddenly upon Elsie Palmer. She was tired and had dropped down on the stairs to eat her dinner, as somebody had been before her that day and taken her favorite window ledge. She had a small tin pail out of which she took a soiled napkin just as the party -- half a dozen people -- turned the curve in the landing and came suddenly upon her.

The child looked up with a scared glance, but it was too late to run. She drew herself close to the stair railing and into as small a heap as possible; and they passed her by, hardly noticing her with a glance. They were not hard-hearted people; but Elsie was simply to them one among three hundred factory hands, most of whom were more or less coarse, ignorant, unkempt -- or appeared so.

But the yellow napkin lay half opened in Elsie's lap, and Paul Hines, glancing down, took in the whole contents, the slices of half-baked, soggy bread with the melted, rancid butter, the piece of cold fat meat, the little withered last year's apples. Such a dinner for that delicate child, after that long morning's toil! Why, Pilot, Paul's handsome greyhound, would have turned up his dainty nose at such a repast. It almost made the boy's heart sick to think of that meager, unsavory meal. It actually half spoiled his own luxurious one as he sat at his uncle's table and wished he could pile a plate for the poor little spinner with the juicy meats, the fresh vegetables, the delicious fruits.

And all the while the shadowy face haunted him, and sometimes it was the little spinner's, and sometimes it was his dead sister's, and often he could not distinguish, because both had melted into one.

That very evening Paul and his aunt happened to be left alone for an hour or two. It was a mere chance. The guests of the day had left, with the exception of one gentleman, who was to pass the night and whom his host had taken out to drive in the early evening.

Paul was very fond of his aunt. She was a lovely woman, tall and graceful, with blonde skin, and golden hair, and eyes of hazel-gray. Paul had not known her a long time, for she was his uncle's second wife, and was a good many years younger than her husband, who was himself in his prime.

But Mrs. Terry -- that was his aunt's name -- had taken a liking to her new nephew from the beginning, for Paul had come now, as he had done before her marriage, to pass his school vacation with his uncle. He had no home of his own, for his father and mother had died some time before his sister, and left Paul the last of his household.

The two sat together that night in Mrs. Terry's own room. It was a pleasant place in which to linger at any hour, but especially pleasant at evening, with its shaded lights, its luxurious chairs and lounges, its graceful brackets and choice pictures. Paul always liked to come in here, and have some half-gay, half-serious talk with his aunt. The woman and the boy were often as merry as two children together.

The house stood in the center of ample grounds, a little outside the busy, manufacturing town. The soft wind of the sumer evening stirred the lace curtains, and brought into the room the sweetness of the flowers outside, which were making the grounds a very Garden of Eden at this time.

While the two sat together there fell an unusual silence between them. They had been talking over the incidents of the day, and matters of that sort.

Mrs. Terry turned suddenly and looked at Paul. His great, bright eyes were regarding her with a kind of solemn questioning earnestness.

"Paul," she said, "you are thinking something about me. What is it?"

If he had stopped a moment to think how the words sounded, perhaps he would not have answered just as he did, only Paul Hines was not apt to think twice.

"I was wondering, Aunt Agnes, if you really have a heart."

"Why, Paul," said Mrs. Terry, a good deal surprised, possibly a little hurt, "have you known me so long, and doubt that?"

"Forgive me, Aunt Agnes," said Paul, very earnestly. "I don't mean, you know, a heart for me -- for anybody you love. I know just how sweet and tender you are there, but I mean a heart for anything poor, and lonely, and helpless, and so far beneath you that it seems as though you did not live in the same world with it."

"Well, Paul," said Mrs. Terry, leaning forward with her lovely face and looking in the eyes with her sweet smile, "there is only one way for you to find out about my heart, and that is to try me and see."

"A boy doesn't like to be laughed at, Aunt Agnes -- there's the rub."

"But I will promise not to laugh at you, dear."

"A boy or a man would be sure to do it," continued Paul, half to himself. "I wouldn't tell one of the fellows at school -- I wouldn't even tell Uncle John for -- for a piece of solid gold as large as that great moon that is shining in at the window."

"Well, Paul," said Mrs. Terry, growing more and more curious. "I am not one of the fellows at school, nor even Uncle John, you know; and as for gold, I don't happen to have a piece as big as the moon up there."

"If you were not a woman, Aunt Agnes -- if you did not seem to me the best, and dearest woman in the world, I should not have courage to tell you."

At these words Mrs. Terry leaned over and placed her small, soft hand in Paul's. She did not utter a syllable. There was no need.

He told her about the little, sorrowful face which he had seen that day before the loom; he repeated the brief talk which had passed between him and Elsie Palmer, and he related also how he had found her afterward crouched on the stairs, with the tin pail beside her, and the dinner which his own dog would have spurned lying in her lap.

"If her face had been without that curious likeness to poor little Edith's," he said, "I might not have thought so much about it. But now I cannot get rid of it; it seems almost as though she were there weaving those endless threads before that great loom in that dark, noisy, dreadful place. I want to do something to get her away from there. Does all this seem very absurd to you, Aunt Agnes? You know you promised not to laugh."

"Even if I had not promised, I should not laugh, Paul, at any feeling which certainly does you honor."

"There now; that's the sort of talk a fellow likes to hear. That girl's face will come back to me -- I know it will -- when I get away off tumbling about on the great ocean, and I shall think of her tired face before that great loom, and of her sitting there and listening for the factory bell, and for the dinner that my dog wouldn't eat, and then I shall think of Edith. If the faces had not been so alike for all the difference! I wish I could do something for that girl, Aunt Agnes."

"But what would you like to do, Paul, dear?" asked Mrs. Terry, more and more interested.

"I should like to take her out of that horrid old mill and give her a chance in the world. I should like to have her go to school and play outdoors and get some color in her poor little famished cheeks. I should like to have her placed in some family where she would have wholesome food and kindly care. I've got money enough to do that. It would not cost a great deal, would it, Aunt Agnes?"

"Oh no; only a few hundred dollars, I should think."

"Well, I could easily save so much out of my allowance. I always get from my guardian all the money that I want, and even if I had to screw and pinch a little to pay the bills, it wouldn't do me any harm. But I'm only a boy. If I should mention the thing to him or Uncle John, it would look so ridiculous and moonshiny to both."

"Yes, it certainly would, Paul," said Mrs. Terry; and now they both laughed together.

"Aunt Agnes, can't you help me?" asked Paul, growing grave in a minute.

"What do you want me to do, Paul?"

"If you could only find some comfortable boarding-house for this girl, and send her to the district school, and see that she had some clothes like other schoolgirls. Would that be such a very great thing to do, Aunt Agnes?"

"No. Certainly, I would do all that cheerfully to oblige you, Paul," answered the lady, a good deal touched. "But I cannot think just now of any place such as you describe. Then, too, your Uncle John is a generous man, but not a sentimental one. What a couple of geese he would think we were making of ourselves."

"But that would not prove we were. Besides the folly would be all on my side."

"Hardly, if I aided and abetted you in it."

"But, Aunt Agnes, it is my secret. Uncle John is not to know."

"I understand all that, Paul. But I shouldn't mind him."

"You would, perhaps, if you were a boy, Aunt Agnes. Can't you think of some place?"

Mrs. Terry sat still a few moments, with a half-amused, half-serious smile on her face. At last she said, half to herself:

"Mrs. Burchard, our old gardener's wife, is a kind, motherly soul. She lost her own little girl about two years ago. This little protegee of yours, Paul, would have the best of homes if she were once under the low, comfortable roof. I might see her and prevail on her to take the girl."

"Will you do it, Aunt Agnes?" asked Paul, with his dark, handsome eyes pleading eagerly with the lady. "When I am out at sea next week, and that little girl's face comes up to me, the face like Edith's, it will comfort me to think it sits no longer sad and weary before that old loom. In that case I shall feel, too, that I have done one good deed before I left my native shores."

Mrs. Terry was deeply touched now. She leaned forward and kissed the smooth, boyish forehead.

"Well, Paul, my dear boy, I will try," she answered.

It was all settled between the two, with nobody to listen but that great, yellow, far-off moon, that filled the June night with her silver light. Mrs. Terry was to manage the whole thing, and Paul was to pay all Elsie Delmer's [sic] expenses out of his own allowance. He would send the money to his aunt as it became due; and "it was all his own," he said; "he had a right to do with it as he pleased."

When Paul's uncle returned with his guest, he little suspected that his wife and his nephew had a plan all cut and dried between them -- a plan of which he was to know nothing. But Paul was right. His Uncle John was a man of excellent common sense and great business shrewdness; but he would have thought this whole matter dreadfully "moonshiny."

* * * * * * * *

"I don't like the sound of the factory bell," said the lady, with a little shudder, and a little shadow came into the brightness of her face.

"Had I known that, I should never have called your attention to it," said the gentleman. "It was a soft, far-away sound at best, but it came musically across the fields and over the river."

The lady smiled now. Her smile was very sweet, and her face, without being precisely handsome, was very attractive. She had fine eyes, whose shade varied a good deal with her mood, and brown hair, and a lovely peach-bloom color in her cheeks.

"I doubt whether the bell was soft and musical to the ears of the operatives," she said -- "to the droves of tired men, and women, and little children, to whom that loud, clanging bell is a terrible fate, ringing them out of their beds in the morning to the day's long, hard, dreary toil. It would not have a 'soft, musical sound' to you, Mr. Hines, even out here in the sunshine, amid these blessed green fields, if you had ever worked in a factory."

"Probably not; but as you have never done that, Miss Burchard, I am quite at a loss to understand why you should hear more than I did in the ringing of that old bell."

The lady did not speak. She turned and looked at her companion with something in her eyes which he could not understand; but it brought up the old shadowy likeness which had struck him when he first met Miss Burchard three months ago, and which had made him seek an introduction to her.

He was so absorbed in thinking of that, that he did not remark her silence; indeed he quite forgot what they had been talking about, as he said:

"I cannot tell you how strangely you remind me at times, Miss Burchard, of one who was very dear to me, and who was laid away under the daisies, on a June day like this, sixteen years ago. It seems only yesterday."

"You must have been a boy then," said the lady.

"Yes; not fourteen; and the little girl -- she was my only sister -- was two years younger. It is only at times you remind me of poor little Edith, but every now and then the curious haunting likeness comes into your face and startles me. I have never seen anything like it except once, long ago."

"And when was that?" asked the lady.

"It was in a factory, the year after Edith died. I saw a little girl spinning cotton-threads before an old loom -- "

The lady gave a sudden start, a swift, bright scarlet came into her cheeks.

"Oh, Mr. Hines, I wish you would tell me all about that!" she exclaimed, with a kind of breathless eagerness.

He looked at her a little doubtfully.

"It happened long ago," he said. "I have not thought of it for years. It was about one of those factory operatives you were speaking of, Miss Burchard."

And again her flushed cheeks, her eager eyes, her parted lips through which shone the soft pearls of teeth, begged him to tell her.

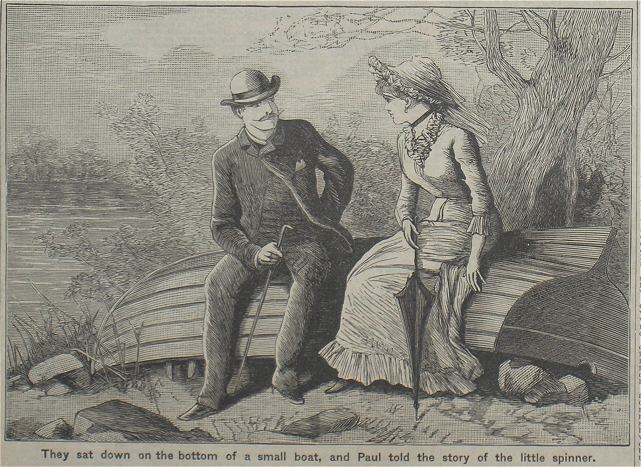

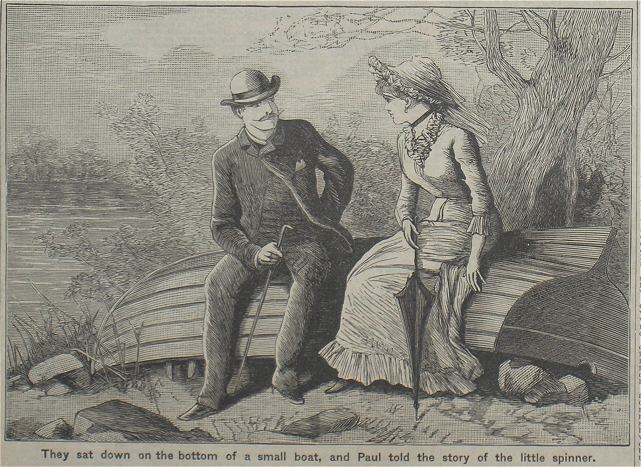

They sat down there on the bank of the narrow river, where they had unexpectedly encountered each other -- sat down on the bottom of a small-boat, which had been turned over, freshly painted in bright stripes of white and red, and left there to dry. The June morning sunshine, and blossoms, and singing robins were all around them.

So Paul told the story of the little spinner whom he had found fifteen years ago in his uncle's factory, and how his heart had been touched at the sight of her pale, tired face when he saw it at the loom and afterward on the stairs; and how that night he and his Aunt Agnes had concocted a plan between them to lift the little girl out of her hard life, find her a new, comfortable home, and send her to school.

Paul went abroad the following week; he knew that his aunt had faithfully and secretly carried out his wishes. For about three years he had transmitted the small sums which were required to defray the bills of his protegee. "Her expenses only taught him a few wholesome lessons in economy," he said, lightly enough.

At the end of three years Mr. and Mrs. Terry suddenly went to South America. Before his uncle left, he sold out his share of the factory. Paul only knew that the kindly, childless old couple -- he had forgotten their names -- with whom Elsie boarded became very fond of her, and had adopted her as their own.

He believed that some good fortune had fallen to them about the time Mr. and Mrs. Terry left Deerville. Some relative in England had died and left the old man his property.

What became of the little girl the young man had never been able to learn. All traces of her and her adopted parents had vanished when, a few years ago, Paul visited Deerville.

"I don't know what has brought this old story up to me," said Paul, turning at last toward his companion. "I hope you will not imagine, Miss Burchard, that I intend to make myself the hero of a boyish romance. I did not think when I began that I should figure so largely in the story."

"How could you help it and tell the truth, Mr. Hines?" said the lady; and she turned her blue eyes, with a wonderful light in them, full on the man by her side.

He wondered why his heart beat so fast as he gazed into their radiant depths.

"Yes; my story has that poor merit, Miss Burchard. It is the truth," said Paul Hines.

The lady had listened silently, as though she were turned to stone, only her face had a hungry wonder and eagerness in it, which led Paul on, almost against his will, through the whole story. If he had looked at her face, instead of gazing at the blue river that went singing and glancing between its green banks to the sea, Paul would have seen that his companion's cheeks grew white while he talked, and then suddenly flamed into scarlet.

"I suppose you would be glad to know the fate of your little factory spinner, Mr. Hines?" she said at last, in a low, quiet voice. "If any good had come to her, any lasting happiness to that poor, starved life through your young help and kindness, it would be a pleasure to you to know it?"

"A real pleasure, Miss Burchard," answered Paul, fervently. "But it is singular how completely I have lost sight of the girl. I can only hope that my boyish effort to rescue her succeeded. If I had more things of that sort to look back upon -- well, I suppose I should be a happier man sitting here to-day."

Miss Burchard sat quite still a few moments. Perhaps she did not hear that last sentence. At all events, she turned suddenly, and said:

"I believe you told me, Mr. Hines, you should be in Deerville next week?"

"Yes; I shall stop over there one or two days on my way to New York. My Aunt Agnes, who is still in South America, wishes me to send her some tidings of her old Deerfield [sic] friends."

"I, too, shall probably be in Deerville at that time," said Miss Burchard in a rapid, decided voice. "I have some business which will take me there. I shall stay at the quiet family hotel of which you must have heard. It is just outside the town. I have a curious fancy, Mr. Hines, that I should like to go over to that old factory where you found the little girl spinning threads so long ago."

"I shall be most happy to accommodate you," answered the young man, a good deal surprised, yet pleased at the desire she had expressed. "The buildings were all standing when I was last at Deerville; but I presume the interior of the factory has greatly changed in fifteen years."

And so their talk that June morning by the river came to an end. Paul Hines knew next to nothing of Miss Burchard's history. He believed that all her nearest relatives were dead.

She was in mourning now for her uncle, who had died only the year before in the quiet little inland village where Paul had first met her. The uncle and niece had boarded here for several summers in a farm-house. Miss Burchard was very fond of the quiet little picturesque town. So was Paul, who was now practicing law in New York, and often ran up here in the summer heats, [sic] to tramp the woods, to row and fish on the river.

Paul Hines was almost thirty now. Culture and travel and fine opportunities of every sort had done much for him, but there had been in him fine and generous qualities from the beginning. They would have made themselves felt in any sphere where fate had placed him.

He had first been attracted to Miss Burchard by some shadowy resemblance which he saw in her to his long dead Edith. The more he saw of her the more he felt the subtle, nameless charm of her presence, and the more he felt assured the heart and mind of no ordinary woman were behind that young, sweet face.

Paul was right. The cotton factory had undergone vast changes since that morning, when, a gay, light-hearted boy, he had gone over it with his friends. The old looms had been replaced by modern machinery, old walls had been torn away, new partitions had been run up at various points -- changing the aspect of many rooms.

Yet the huge frame stood intact. There were the same small, dingy panes of window glass, through which the hot summer sunlight poured as Paul Hines and Miss Burchard went over the cotton factory.

They were a handsome couple, the operatives thought -- men and women who stopped their work a moment to stare with vague wondering curiosity after the pair who belonged to a world so far outside their own.

There were the same noise and heat and dust as of old. Miss Burchard said very little. She gazed intent, breathless, on all that was going on around her, but it seemed to Paul that once or twice she shuddered a little as she leaned on his arm while they made their slow rounds.

"Does it tire you?" he asked.

"Ah, no, thank you, not in the least," she answered promptly.

At last they mounted the topmost flight and reached the highest room. There, too, everything was changed. The looms were all gone, but the roar and clang, the sweep and rush of wheels and gearing brought up the old morning out of his boyhood very vividly to Paul Hines.

"I am almost certain it was at this very window that the loom stood when I saw the little spinner," he said to Miss Burchard, and he stepped up to the window-panes and tried to look through the glass.

"Oh, no!" she answered, moving quickly to the next window, and she turned around, and stood very still, looking Paul straight in the eyes with her own, that fairly dazzled him. "It was at this very window that Elsie Palmer sat that day; it was here that her loom stood."

"But how do you know, Miss Burchard?" asked the young lawyer, amazed and bewildered.

"I will show you something else," she said, and she moved rapidly toward the door, and Paul followed her like one in a dream.

She stood still on the landing; she pointed to the third stair. "It was there on that third step," she said, in a voice that wavered a little, with all the memories that were crowding on heart and brain. "She sat there, with the little tin pail on one side, and the old napkin and the hard, tasteless food were in her lap. You came by and saw it all, Mr. Hines. Do I need to prove to you now that Elsie Palmer, the little spinner, stands before you?"

Before they left Deerville Paul Hines knew all there was to tell; knew how Elsie had taken the name of the people who had been to her in all things a father and mother.

The gardener's brother had died suddenly in England. he was a childless widower, and left all his property -- a small but comfortable fortune -- to his brother.

There had always been a mystery in Elsie Palmer's mind about her adoption by the Burchards. Mrs. Terry had kept Paul's secret well, and never told them what his part had been in the whole matter; and they always supposed that the warm-hearted lady had taken pity on the sweet, childish face of the little spinner, and so removed her from the family.

Elsie had only found out the truth when she sat that morning by the river-bank on the old upturned boat, and Paul Hines had told her his own story and hers.

And before the two left Deerville, he had told her another story, and that too was hers, for before the last moon of that summer had waned Elsie Palmer Burchard was the wife of Paul Hines.

-- New York Weekly, Sept. 8, 1884

Special thanks to Dr. Lydia C. Schurman for making this issue of The New York Weekly available for photographing and transcribing.

Please do not use on other pages without permission.