Evidence suggests that the woman writing as Carrie L. May was Caroline Louisa Davis, born in Massachusetts on April 24, 1832, to George Davis (1803-1888) and Nancy (How/Howe) Davis (1811-1886). [1] Caroline may have been the eldest child, for the 1850 census shows that the household consisted of 18-year-old Caroline, her parents, and her four younger siblings (Augusta, 16; George, 14; Charles, 12; Eugene, 5). Her father, a lumber surveyor, owned real estate valued at $2500, and the family was living in Boston. [2]

On September 5, 1854, Caroline L. Davis of Boston married Samuel J. May (1827-1859). Samuel was a newspaper editor born in Connecticut; he apparently spent some time in Boston before moving to Sacramento in 1849. There, he worked for various local newspapers including the Californian, Democratic State Journal, and, later, the Tribune, the California American, and the Daily Bee. [3] Initially, the couple may have lived apart, for Caroline appears in the 1855 Massachusetts census in Boston with her parents. Samuel is not listed in that census and was, presumably, in California.

Carrie appears to have joined Samuel out west sometime thereafter, and, in Sacramento on July 3, 1856, the couple had a daughter, Carrie Augusta. Barely two months later, on September 12, the infant died on September 12, possibly of accidental poisoning. [4] More tragedy soon followed: Samuel had suffered from consumption for some time, and the Sacramento Daily Union reported that by December 1859, he was “wholly unable to attend to business, being confined to his room and a great part of the time to his bed.” He died December 28, 1859, leaving Carrie alone in Sacramento. [5]

By mid 1860, Carrie May had apparently returned to Boston and was again living with her parents, for “Caroline L” appears in the Davis home (albeit without May as a surname). [6] The 1865 and 1870s Massachusetts censuses record her as still residing in her parents’ home (under the names Caroline May and Carrie L. May, respectively), with no occupation shown. The household included her youngest brother Eugene, who, by 1869, was working as a printer. [7] That occupation suggests that perhaps he -- or one of the Davis’s neighbors with a similar livelihood -- might have helped Carrie find a publisher as an outlet for her creative efforts and a way of earning income.

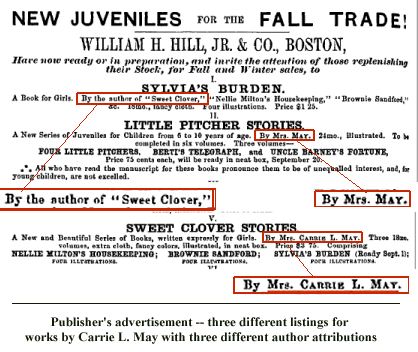

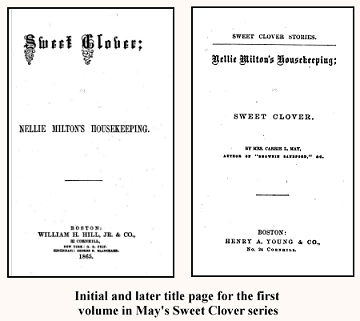

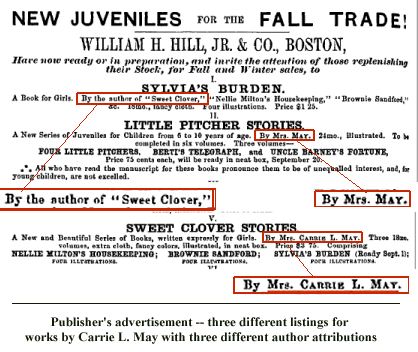

All of the books published under the names “Mrs. May” and “Carrie L. May” were originally handled by a Boston firm, William H. Hill, Jr., & Co., and all appeared between the years 1865 and 1869. The first book, Nellie Milton's Housekeeping; or, Sweet Clover was initially issued anonymously in 1865 under the title Sweet Clover; or, Nellie Milton's Housekeeping. and advertised as the start of the "Clover Series." Subsequently, the title and subtitle were reversed and minor formatting changes introduced: May's name (as "Mrs. Carrie L. May") was added, and the series title "Sweet Clover Stories" appeared at the top of the page. The second volume, Brownie Sandford; or, The Recovered Pearl was issued in 1866 and appears to have employed the new format and series title.

In 1867, along with the third volume of the Sweet Clover series, Hill issued a boxed set of three more books by May as the start of a new series, Little Pitcher. Rather than using May's full name, the Little Pitcher books showed only "Mrs. May" as author, both in advertisements and on their title pages. The publisher may have viewed the different names as a way to distinguish between the two series or a way to make it less obvious that the same person was behind both sets of books. The following year, however, when Ruth Lovell; or, Holidays at Home, the final installment in the Sweet Clover Stories, was published, the title page acknowledged that May was also the author of the Little Pitcher Stories.

May's Sweet Clover series received a fair amount of attention from reviewers, almost all positive. A few mentions were perfunctory, suggesting limited perusal of the book. ("What Sylvia's Burden really was, the young readers will not thank us to inform them when so pretty a book will do it so much more agreeably," read the notice in Banner of Light, an observation that might have been more apt had it actually appeared amid reviews intended to be read by children.) Other reviews, more detailed, spoke favorably of story and moral tone. Arthur's Home Magazine (edited by T. S. Arthur, whose Ten Nights in a Barroom had been published in 1854 ) paid particular attention to Sylvia's Burden, providing an extended summary: "The story [tells] of a poor crippled girl whose deformity has roused the hatred of a drunken father, and the knowledge of this hatred is Sylvia's burden. But God raises her up many kind friends, and she learns the power of redeeming love . . . and finally, by her consistent Christian life, wins a place even in his wicked heart." The review concluded with the observation that the book "will please the majority of our young readers." Godey's Lady's Book offered a more succinct but still favorable review, remarking, "The story is a someone sad one in its progress, yet the ending is bright and cheerful." [8]

In contrast, May's Little Pitcher series attracted barely any notice. The Round Table, the only periodical found that reviewed the series, addressed the first three volumes as a unit, observing only that they were "pleasant little chronicles of the every-day life of four little cousins -- styled, by the old allusion, Four Little Pitchers -- and without any offensively obtrusive moralizings" and suggested that they would "benefit as well as amuse children under twelve years." [9]The Little Pitcher series concluded in 1869, with the three new volumes added that year. No other publications by Carrie L. May appeared after the two series ended, perhaps indicating the author had found other outlets for her energies. [10]

Although May was still in Boston and living with her parents when data for the 1870 census was collected, she returned to California sometime thereafter. On May 8, 1873, Caroline L. May married Enos Hine Smith (1825 - 1888) in Sacramento. [11] Born in Connecticut, Enos moved to California in 1849, and, for several years thereafter, conducted business in Sacramento as part of the firm Scranton & Smith. (His years in Sacramento thus overlap with Carrie's first husband, Samuel J. May.) Enos later moved to “a large ranch at San Pedro Point, San Mateo County.” [12] The 1880 census records "E. H." and “Carrie” on a farm in that region, along with three farmhands. Eight years later, on October 12, 1888, Enos died in San Francisco. [13] After Enos's death, Carrie appears to have remained in San Francisco, where she died July 29, 1894. She was buried in the Sacramento City Cemetery alongside both of her husbands and her daughter. [14]

[1] Several factors can make it difficult to compile biographical information about an author. A lack of specific information (such as birthdate or names of relatives) in biographical dictionaries coupled with a common name and lack of identifying information in published works (such as relatives' names in dedications) and an absence of documentary evidence in archives, makes it difficult to move beyond speculation in tying names in historical records to names on published books. Such is the case with Carrie L. May: There are no entries on Carrie L. May in works such as American Authors and Books, North American Authors Deceased Before 1950, or similar sources. Her books contain no dedications. That said, a study of census records uncovers one woman regularly listed as Carrie L. May whose demographic data correlate with the dates of the series books published by Mrs. May as well as demographic patters of series authors and whose circumstances strongly suggest that she could be the author of these works. The biographical sketch here outlines that Carrie L. May's life.

[2] 1850 U. S. Federal Census, Boston Ward 11, Suffolk, Massachusetts; Roll: M432_338; Page: 208B, Ancestry.com. Caroline's father's occupation in the 1850 census is “surveyor”; later city directories identify him as a “lumber surveyor.”

The family has not been located in the 1840 census, so Caroline may have had older siblings who had moved out by 1850. An additional complication in tracing the family is that there was apparently a second George Davis ( -1875), a blacksmith, also married to a Nancy H (1813-1856), in Massachusetts, so birth records for children born to George and Nancy Davis do not necessarily identify Caroline's siblings. For the other Davis family, see Almira Larkin White, Genealogy of the Descendants of John White, vol. 2 (Chase Brothers, 1900): 539-40.

[3] Massachusetts Vital Records 1840-1911; Dr Samuel J. May Find a Grave. He is, inexplicably, referred to as Dr, though there is no indication May practiced medicine or had attained a doctorate. See also note 5.

[4] Carrie Augusta May Find a Grave. The website reports that Carrie “died of accidental poisoning”; the information appears to be from Victoria Marsh, comp., "Sacramento Historic City Cemetery Burial Index for the years 1849-2000," Old City Cemetery Committee. The child’s obituary in the September 13, 1856, Sacramento Daily Union, accessible online at the California Digital Newspaper Collection, gives her age but no cause of death.

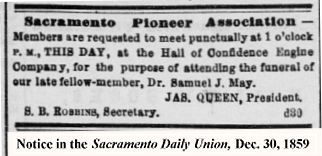

[5] "Death of Samuel J. May," Sacramento Daily Union, Dec. 29, 1859 To add to Carrie's loss, there appears to have been some confusion about Samuel's burial. On January 9, 1860, a section in the Sacramento Daily Union's "City Intelligence" column titled "Violation of Cemetery Ordinance" charged that May's body and several others had been buried without the proper permits (in large part because of city politics and the election of a new Superintendent of the City Cemetery late in December). The "Sacramento Historic City Cemetery Burial Index" lists him twice -- or, more accurately, assigns him two plots, with a note that he was reinterred. The second plot locates him next to his daughter Carrie. Perplexingly the burial index lists Samuel J. May as "Dr." and his occupation is shown as a "druggist"; the entry referencing the reinterment includes a different occupation, "news editor." Several of the news stories about Samuel's death also refer to him as "Dr. S. J. May"; since they clearly refer to the S. J. May buried in Sacramento on December 30, it is the same person and the use of "Dr." remains unexplained. (See for example, "Sacramento Pioneer Association," Sacramento Daily Union, Dec. 30, 1859, and "City Intelligence," Sacramento Daily Union, Jan. 2, 1860.)

[6] 1860 U. S. Federal Census, Boston Ward 11, Suffolk, Massachusetts; Roll: M653_524, Ancestry.com. The page in the 1860 federal census; the page listing her is dated July 31, 1860 -- although she appears as Caroline L Davis, rather than Caroline May. Her entry for 1865 in the Massachusetts census is as Caroline May, widowed.

[7] The first record of Eugene’s employment located is the 1869 Boston City Directory, which calls him a printer; the 1870 census also identifies his occupation as printer. A number of the Davis's neighbors were connected with bookselling, publishing, or printing, at least judging by the census entries: in 1855: Edward Clark, 16, bookseller, and George L. Hall, 35, bookbinder; in 1860; Henry A Gane, 41, bookbinder; in 1865, George Lenard, Jr, 32, book dealer; in 1870; Marvin Theophilus, 74, printer.

[8] "New Publications," Banner of Light, Nov. 16, 1867: 4; Untitled review, Arthur's Home Magazine 31 (Jan. 1868): 68; "Literary Notices," Godey's Lady's Book 76 (Jan. 1868): 98.

[9] "Children's Books," Round Table, Nov. 30, 1867: 358.

[10] Prior to the publication of the series, several short stories and poems by a "Carrie May" had appeared in magazines in the late 1850s. Several from 1857-58 identified the author's location as "Saratoga Springs" or "Saratoga Water Cure"; another, a short story titled "Just My Luck" from 1859, may originally have been published in Ohio Farmer. Whether any of these were the work of Mrs. Carrie L. May remains undetermined. It is perhaps worth noting that one of the stories, "Leisure Moments," from the December 4, 1858, issue of Life Illustrated is primarily a conversation between two women, "Aunt Mary" and "Mrs. Lee"; the children in the Little Pitchers stories belong to two families, that of John Lee and his sister Mary Waters. ("Leisure Moments," written for an adult audience, advocates for women improving their minds rather than devoting too much time to creating elaborate attire for themselves or their children.)

[11] "Married," Sacramento Daily Union, May 9, 1873. That the Carrie May who married E. H. Smith was the widow of Samuel J. May is confirmed by their gravesite. It has a common marker: on one side, E. H. and C. L. Smith (thus, Enos and Carrie); on the other, Samuel J. May and baby Carrie Augusta (thus, her first husband and child). See also note 14.

[12] "Death of Enos H. Smith," Sacramento Daily Union, 13 Oct. 1888: 5. Enos's whereabouts in 1870 are uncertain. It is probable that he is the Enos H. Smith, age 45, born in Connecticut, listed as a farmer in San Joaquin Township, Sacramento County; there is also, however, an E. H. Smith, mail carrier, also age 45 and also born in Connecticut, in Mariposa.

[13] U. S. Federal Census 1880, Township 1, San Mateo, California; Enumeration District: 236; " Death of Enos H. Smith."

Judging by the 1880 census, Carrie's life in California may have been quite solitary. Most of the neighbors on either side of her were from Italy, and a number of those household members are simply listed as "Italian No. 1," "d[itt]o No. 2," "d[itt]o No. 3," etc., with a note from the census taker that he "was unable to get [most of] the names." Smith's name appears on page 19 of the census. All the families after his are listed as "Italian no [#]"; the household immediately preceding his consists of four Chinese farmers or farmhands; others in the immediate area include a solitary woman from Pennsylvania (sharing her household with an Italian farmhand), and another large Italian home, most of whose inhabitants are again identified only as "Italian no [#]."

[14] Obituary, San Francisco Call, July 31, 1894: 8. The obituary identifies her as the "widow of the late Enos H. Smith" as well as the "sister of George H. and Charles H. Davis of Boston," which makes it evident that it is Caroline Louisa Davis. The July 30 obituary in the same paper misidentifies her husband as " the late Ehenos H. Smith of Roston [sic]."

[15} "Caroline L. Smith," Find a Grave; the top photo on the page shows one (more recent) larger marker with all four names. See also note 11.