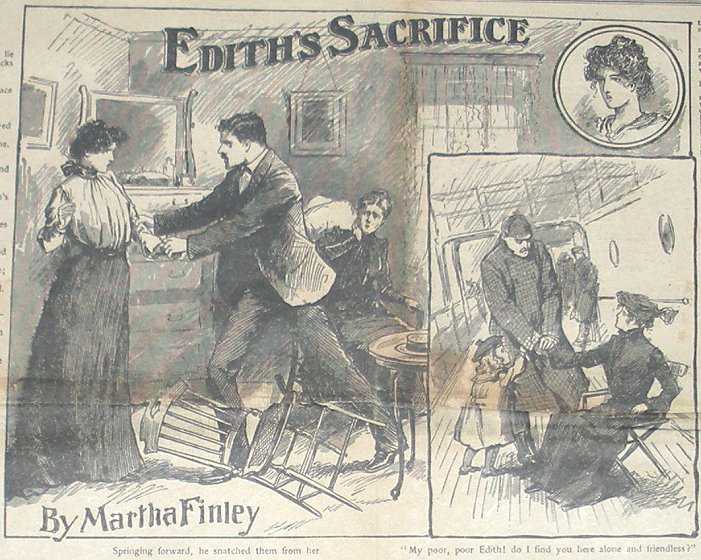

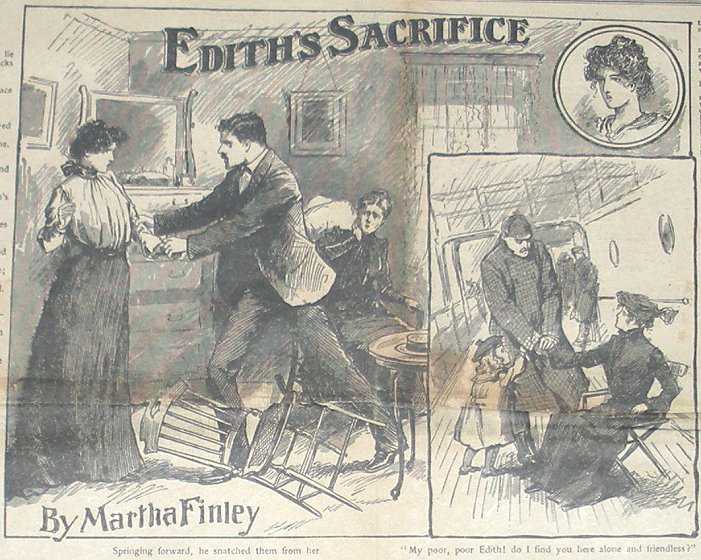

Edith's Sacrifice

----

By Martha Finley

----

CHAPTER I.

THE WAYWARD SON

One other minor similarity perhaps merits quick mention. Grandmother Elsie, volume 8 of the Elsie Dinsmore series, introduced two major characters, the widower Captain Raymond (formerly in the navy) and his daughter, Lulu. "Edith's Sacrifice" also includes a young girl named Lulu and her widowed father, Mr. Randolph ("a good hand at managing a boat"), who play important roles in the last section of the story.

----

By Martha Finley

----

CHAPTER I.

THE WAYWARD SON

The dwelling -- a substantial farmhouse, large, roomy, and wearing both without and within an appearance of comfort and opulence -- stood on the share of Delaware Bay, the grounds sloping down to the water's edge.

It was a summer's afternoon, the sun nearing the west. On a balcony overlooking the bay two ladies were standing. The older was a woman of middle age, tall, well formed, and with a face that was not unpleasing, albeit sadly wanting in firmness and decision. In this latter respect it differed greatly from that of the other -- a girl of eighteen; yet the likeness between the two was sufficiently striking to proclaim their relationship.

Edith was not beautiful, but there was calm strength in the outlines of her well-shaped mouth and chin, and the full, dark eyes were liquid and sweet in expression; she had a clear, brunette complexion, and an abundance of soft, glossy black hair tastefully arranged in braids and bands. In person she was like her mother, and her attitude at this moment was full of grace.

A ship could be seen in the offing, standing out to sea, every bit of canvas spread to catch a light breeze from the northwest. Onward she sped over the dark waves like a giant bird with snowy wings, her sails looking very white and pure in the brilliant sunlight. The eyes of both ladies were fixed upon her, following her movements with absorbing interest. A few moments more and she had disappeared, the very topmost part of her masts having sunk below the horizon.

"There, she is gone!" exclaimed the girl. Then turning to her companion: "Mamma, you are tired; you have stood too long. Will you go in now.?"

"No, Edith, this breeze is delightful. I shall stay here for the present."

"Then you must have a comfortable seat." She stepped in at the open-sitting room door, and returned in a moment, bringing a light, cane-seated rocking-chair. "There, sit down in this, mamma. How glad I am that you are well enough again to enjoy being out here."

"Indeed, Edith, I can't enjoy anything very much while your father gives me no peace of my life for scolding about poor Nelson," answered the mother, in querulous tones.

Edith sighed.

"I wish Nelson would do better; it is a great shame he should be such a worry to you both."

"I don't blame my poor boy -- at least, not entirely; it's more the fault of your father's over-strictness; he's not willing to allow him any pleasure."

"What sort of pleasure does Nelson want that papa refuses him?" asked Edith, who was privately in the opinion that her father was altogether in the right.

"Dear me, Edith," answered her mother, petulantly, "what a disagreeable way you have of pinning one down to particulars. Of course I didn't mean that some of the things your father complains of were not wrong in Nelson; but the boy wouldn't act in that way if he wasn't just driven to it by being held in with too tight a rein. Think of your father scolding because he -- a young man within a few days of his majority -- has been away since yesterday morning without letting us know where he is."

"But, mother, it is so nearly all the time of late; and often not for one day and night only, but for three or four. And you know father said he had been wasting money, and -- "

"There, that will do, Edith. I hear enough of that kind from your father. What is that yonder, coming up the bay?"

"A skiff -- ours, I think -- with Nelson in it and Cecil Randolph," and a charming blush suffused Edith's cheek.

They watched the tiny vessel as she drew nearer and nearer till she had reached a little pier at the food of the garden, where the young men made her fast. Then springing out, they came up the path to the house. Nelson bounded up the steps into the balcony, while Randolph, standing below, lifted his hat to the ladies, and with a persuasive smile invited Edith to a row with him upon the bay.

"If mamma is willing," she answered, returning the smile, while again the color deepened on her cheek.

"It's dangerous; I'm always uneasy," began the older lady.

But Randolph answered:

"Not to-night, Mrs. Delano; the water is unusually calm. And I leave it to Nelson if I am not a good hand at managing a boat."

"Capital!" replied the person appealed to: "he'll bring her back safe, I'll warrant you, mother." He had gone behind her chair, and leaning down so as to bring his lips close to her ear. "Let her go," he whispered; "there isn't a bit of danger; and I want you to myself for a while."

"Well, Mr. Randolph, I'll trust you; but don't keep her out too long. Edith, I shall be uneasy if you are not here before dark."

"Yes, mamma, I will remember. We will come home in good season. In one moment, Cecil; I must get a hat and jacket."

She was running into the house, but turned back again to say:

"But, Nelson, you have had no supper. And Cecil -- he has not been to tea either, has he?"

"Don't keep him waiting," answered her brother, a little impatiently. "We had a late dinner; and you can get us something when you come home."

Randolph, declining Mrs. Delano's invitation to take a seat upon the balcony, stood where he was till Edith joined him. But that was not long; scarcely ten minutes had elapsed from the landing of the two young men ere the exchange of passengers had been made, and the skiff was again gliding over the water.

"There, they are fairly off! And now where's father? out of earshot, at least, I hope."

It was Nelson who spoke, and there was something of sullen anger in the tone of the last words.

"Quite, Nelson; he went out directly after tea, saying he should be gone for an hour or so."

"Well, mother, what have you for me?"

"Nothing, my son. I wish I had all you want; but I can't coax so much as a dollar out of your father. He says you are dreadfully extravagant and wasteful."

"The old song!" cried the young man, fiercely; "but I tell you I must and will have some money. I don't owe very much -- a mere trifle of ten dollars here, and twenty or thirty there -- but some of the fellows are growing quite insolent and I must find a way to stop their mouths. Besides, I have a splendid chance to make my fortune, if I only had a few thousands to invest just now. And, mamma, you can help me to them, if you will."

"I don't know how you can say that, Nelson," she answered, peevishly, "when you know perfectly well that I haven't a dollar at my command."

"I know you had ten thousand when you married father, that the farm was bought with it, and a mortgage on it to that amount given you."

"And what of that?"

"Just this, that you can foreclose that mortgage whenever you choose, get the money and give me a share of it," he replied, boldly.

His mother looked startled.

"Nelson, I can't; your father would be dreadfully angry; and it wouldn't be treating him well."

"Is he treating me well? Come, now, mother, you know he isn't, and can you refuse to help me?"

"But to sell the farm, our home, Nelson. Where could we go, and I so feeble, too?"

"Why, don't you see, it wouldn't be giving up the farm, but only making father own it instead of you, while you get your money back into your hands to do what you please with."

"Is that so?"

"Of course, it is. And by the time the thing's all arranged I'll be of age, and can do as I please. And if you'll give me a couple of thousands, I'll make them twenty or thirty in less than a year. Come, mamma, say you will give me a note to Perkins directing him to foreclose at once, and I'll see to it; you shan't have any more trouble about it."

"Oh, Nelson, don't ask it; you know I don't like to refuse you, but I can't bear to make your father so angry with me."

"He'll get over it again, and you'll feel well paid when you see me a rich man. Come, mother, I know you're very fond of your only boy, and can't be so selfish as to refuse to help him on the sure road to fortune."

Mrs. Delano was a second wife. There were several sons and daughters by the first -- all married now, and in homes of their own -- but Nelson and Edith were the only children of their mother. From his very birth this, her first born, her only son, had been Mrs. Delano's heart's idol, in whom she could see no wrong.

The spoiled child had matured into the "fast" young man, with little or no principle, and utterly selfish. He was deceiving his mother in regard to his plans and wishes. Thinking solely of his own advantage, caring for nothing else, and believing that his father, though by no means poor, would not be able to raise the ten thousand dollars on so short a notice, Nelson hoped by the sudden purchasing of the mortgage, to compel the sale of the farm, and to buy it in himself for a mere trifle.

Mrs. Delano had always found it a difficult matter to refuse anything to this darling of her heart. She was but a weak woman by nature, and a stroke of paralysis the year before had left her with less than her original strength of character. Nelson's arguments and persuasions prevailed at length; she yielded to his request, and he went away fully empowered to carry out the desired measure. Little cared he that he left his mother in a sad state of nervous trepidation at the thought of her husband's anger when the blow should fall.

Meanwhile the lovers -- for such they were -- had greatly enjoyed their row upon the bay. The boat was now headed toward home, for the sun had set, and though the western sky was still gorgeous with crimson, purple and gold, twilight would ere long deepen into night. Cecil was speaking, in low earnest tones:

"Edith, my darling, I don't know how to wait. Your mother is much better now; why must my happiness be longer delayed?"

"She is still far from strong, Cecil, and not yet willing to give me up."

"I'm afraid it's dreadfully selfish in me, but I can't help remembering that she has your father and brother, and that I am all alone."

"Yes, just now; but you can stand it for a while; we are both young, and can afford to wait."

"But I need a good wife to keep me straight; you don't know what mischief I may get into if you don't come and look after me," he said, half seriously, half in jest.

Edith smiled.

"I am not afraid to trust you, Cecil."

"I wish you loved me too well to let me go on roughing it alone."

"You know I do care for you, perhaps quite as -- as much as you deserve," she answered, with an arch look and smile, blushing, too, as she spoke; "but you must be content to wait a while. I hope to see mamma better soon, enough so to be no longer so dependent upon me, and then -- "

"Then you must, you will be mine?"

"We shall see. There, don't frown, for you know it is duty, and not inclination, that keeps me from letting you have your own way altogether. Which -- now I think of it -- might not be at all good for you." And again that pretty, arch expression flitted over her face.

"Ah, I seem in no danger of being injured in that way just at present," he remarked, as the boat touched the pier. Then helping her out: "And now, do you intend to send me away with only this slight taste of your company?" he asked.

"No, come in and spend the evening with us."

"I want to spend it with you, and no one else; can't we have a stroll together?"

"If mamma does not need me. Wait one moment while I run up to the house and see how she is."

Edith found her mother in a state of nervous agitation and excitement that threatened hysteria; evidently in no condition to be left alone.

"Hand me the smelling-salts, Edith, and come and fan me," she said, heaving a long-drawn, sobbing sigh. "You are very thoughtless to leave me alone so long."

"Mamma, dear, you seemed so much better, and Nelson was with you when I went. But I shall stay with you for the rest of the evening. What has happened to make you so much worse?"

"Nothing has happened, and you know I can't bear to be questioned when I am ill. But you will never learn consideration."

Waiting a few moments till the remedies began to have their desired effect, Edith ran out for a word of explanation and regret with Cecil -- who refused to come in, and went away half vexed with her, and wholly so with her mother -- then returned to her port, to pass the next three hours in patient, untiring efforts to soothe and calm the perturbed spirit of the invalid, and relieve her bodily suffering.

The next morning, and for several days afterward, Mrs. Delano was so much worse that the hope of satisfying Cecil seemed to Edith to be receding farther and farther into the dim future.

Mr. Delano was not an unkind husband, but like most men, he could bear but little of the confinement of a sick room, and had small patience with nerves. So the heavy end of the nursing fell upon Edith, as it had always done since she was old enough to take it up. The girl was devotedly attached to both parents. She could hardly have told which was the nearer and dearer; and her father was very proud and fond of her.

---

CHAPTER II.

THE SEPARATION

It was a bright, sweet morning, the air was delicious with the soft freshness of the sea, and the scent of roses and heliotrope coming in from the garden. Breakfast was over, Mr. Delano had gone out, and Edith, having made her mother comfortable in her easy-chair, which she had drawn up to a window overlooking the bay, sat down to her sewing, trying at the same time to entertain the invalid with cheerful talk.

Mrs. Delano listened absently, and gave a sudden start as her husband's step was heard in the den without.

"Your father has returned very soon," she remarked, with a tremble of apprehension in her voice.

Ere Edith could answer her father strode into the room, and catching sight of his face, the girl sprang up with an affrighted cry:

"Father, father, what -- what has happened?"

He put her aside -- not roughly, but with determination -- and stood before his wife. She lifted one glance to the white, stern, almost rigid face, and dropping hers into her hands, burst into tears, wailing out:

"You needn't look at me like that, Robert Delano! What have I done to deserve it?"

"What, woman? That which puts an impassable gulf between you and me. You are no longer wife of mine. I will have a divorce as soon as it can possibly be procured. You would ruin your husband to provide a spendthrift the means for living in drunkenness and debauchery. Well, you have chosen, and you may abide by your choice. I wash my hands of you now and forever. I shall return you every cent you were worth when I married you, and then you may go your way, and I will go mine."

"Father, father! oh, what are you saying?" and Edith's arms were around his neck, her pale, terrified face upturned to his.

"What I will stand to, Edith. Your mother and I must part; but -- "

Mrs. Delano was in violent hysterics, and Edith ran to her relief, while the husband and father turned and left the room, utterly heedless of her condition.

An hour later Edith sought him in the library, where he was pacing to and fro in silence and solitude. There was keen anguish in the eyes she lifted to his, questioning, too, though no sound came from the pale, quivering lips.

He took her in his arms, and held her close.

"Edith, my child, you will not forsake me?"

She clung to him, hiding her face on his breast.

"You love me, Edith?"

"Dearly, dearly! but -- not better than I love my mother. Oh, what is this dreadful thing that has come between you?"

"Something that proves her to be utterly destitute of affection or even respect for me. She has foreclosed that mortgage without having given me so much as a hint that she contemplated such a measure; that is, I was notified this morning that it will be foreclosed within a few days unless paid off. Ah, I see you know nothing about it." And he went into an explanation.

Edith listened in silence, but with close attention. She, too, was indignant, yet pleaded for her mother.

"Have I been well treated?" he asked.

"No, oh, no, it is shameful! But it is Nelson's work. You know mamma never could refuse him anything. And I -- I am sure her ill health has affected her mind. Oh, father, be forgiving!"

"No; she knew well enough what she was doing. She has made her choice, and let her abide by it," he answered, in a tone of bitter resentment.

Still Edith pleaded, but in vain; he was not to be persuaded, and at length, nearly heartbroken, she left him and went back to her mother, who was again in need of her attention.

Edith's love for both parents was so deep and tender that it was agony to think of resigning either; yet now she must choose between them -- choose to forsake the one for the time being at least, perhaps forever -- if she would cleave to the other.

Those were soul-trying days which followed. Mr. Delano refused to see his offending wife, and having -- by the assistance of his older sons -- paid off the mortgage in season to prevent its foreclosure, he signified his pleasure that she should leave his house at the earliest possible moment.

It was Mr. Perkins, the trustee of Mrs. Delano's property, who delivered this message, when paying over the money into her hands.

"Oh, I can't take it! I can't! I won't have it!" she cried, bursting into sobs and tears. "Edith, carry it to your father, and tell him to keep it and the farm, too, if he will only be friends with me again."

Edith waited for no second bidding, but most joyfully hastened to obey. She would not delay a moment; thus giving her mother time to change her mind or herself to consider whether there was the smallest hope that her father would relent, and glad was she that Nelson was not there to exert a baleful influence over Mrs. Delano's weak mind, take possession of the money and prevent the hoped for reconciliation. The young man had not ventured into the house since the serving of the notice upon his father.

Mr. Delano was in the library, and thither Edith flew, carrying the money with her. She laid it down before him, delivered her mother's message, and made an earnest, passionate appeal in her behalf.

"No, it is too late," he said, with stern decision; "your mother has made her bed, and she must lie in it."

"Father," urged Edith, desperately, "the Bible gives, our Lord acknowledges, but one just and righteous cause for divorce, and my mother is guiltless of that."

"I do not insist upon divorce," he answered, turning moodily away; "but I must and will have an entire separation."

"Oh, father, for my sake!" cried Edith, sinking on her knees before him, and lifting her clasped hands and streaming eyes to his face; "have you no pity for me? Father, I love you so dearly, how can I bear to part from you?"

"You, my darling, I am not sending you away," he said, taking her in his arms and caressing her tenderly. "No, Edith, my pet, you must stay with your father."

She made no answer, but clung, weeping, about his neck.

"You must not leave me," he said, repeating his caresses; "tell me you will not."

"Oh, father!" she sobbed, "you are tearing my heart in two! I don't know which of you I love best; but my mother needs me most. You are well and strong, but she is feeble and ill; you have other sons and daughters, while she has but Nelson and me; he would not care for and nurse her as I do."

"True enough, he cares for nobody but himself. He'll waste all his mother's substance, and then leave her to perish with want."

"No, no," she shuddered. "I must go with her and save her from such a dreadful fate."

"You will have a hard time of it; I don't like to think how hard. Better stay with your old father, my little girl," he said, fondly, stroking her hair.

"Oh! papa, I wish -- I wish I could without leaving mamma; but she cannot do without me."

"And Cecil?"

Edith's cheek grew deadly pale, and for a moment she seemed unable to speak; then low and tremulously came the words;

"I cannot forsake my weak, suffering mother -- even for him."

"You will think better of it, I hope," he said, releasing her. "Think well before you decide a matter that may affect your whole future life. Here, take this back to your mother; I will have none of it," he added, putting the money into her hands again.

Edith received it in silence, turned away weeping bitterly, and left the room.

Nelson was with her mother, striding up and down the room, looking flushed and angry, while Mrs. Delano lay back sobbing among the cushions of her easy-chair.

"It is very hard to have you talk so after bringing me into all this trouble," she was saying as Edith opened the door.

"But it was such nonsense, such absurd folly to go and send that money right back to him after all the bother we've had getting it," Nelson answered, impatiently. "I wouldn't have believed you could be such a confounded simpleton."

"Nelson, how dare you speak so to your mother!" cried Edith, her eyes flashing with indignation.

But he had caught sight of the roll of notes in her hand, and springing forward, snatched them from her, paying no heed to her words.

"So he has rejected the overtures of peace and sent the money back. Good! capital! Now, mother, we'll go away somewhere and set up for ourselves, you and I. I'm delighted to get hold of so much of the needful, though unfortunately, it comes too late for the investment I spoke of."

"Mrs. Delano did not seem to hear. Turning to her daughter:

"What does your father say?" she asked, with white and trembling lips.

Edith leaned over her and delivered her father's message, softening it as much as she could.

Mrs. Delano clasped her hands with a gesture of grief and despair.

"Edith! Edith! what shall I do?"

"Mother, I don't know; but we must go away to some cheap place, and try to live on this money. I will work to support you, if necessary, and wait on and nurse you as tenderly as I can."

Nelson was standing by a table, counting the notes.

"I think we can do very well without you, Edith," he said gruffly; "you'd better stay where you are, and take care of the old man."

"Nelson, I will not have you speak so of my father. You seem to have no respect for either of your parents," she answered, in indignant anger. "And that money is not yours, but mamma's, and she, not you, is the proper person to decide our future course."

"I think you'll find she'll do about as I say, however," he answered, with a sneer.

This was no idle boast, as Edith feared even while she heard it. Finding there was no hope of reconciliation with her husband, Mrs. Delano gave herself up to her son's direction and control. He decided that they would go to Europe; the voyage would probably benefit his mother's health, and he wanted to see something of the world. Edith objected on the score of expense, but was overruled. There were places in Germany and Switzerland where the cost of living was small, Nelson said, and to one of them they would go. All this was determined upon ere he left his mother and sister that same afternoon.

It was night. Edith had assisted her mother's preparations for retiring, had seen her safely to bed, and now with a heavy heart went to seek her father.

The full moon was sending down floods of silvery light over sea and land, and as the young girl stood for a moment in the open doorway, she could see Mr. Delano's tall, manly form pacing slowly to and fro across the garden. He saw her, also, and beckoned her to his side.

"You were looking for me, daughter?"

She bowed a silent assent laid her head on his breast, and clung to him with bitter weeping.

He folded her close with a tender caress, then sighing, asked when and where she would go. She found voice to answer his questions, and to ask what he would do.

"Since I am to lose you," he said, in tones of deep sadness. "I shall have to find some stranger to be my housekeeper, for, as you are well aware, your sisters have families of their own to attend to, and neither of them can come to me. You will sometimes think of your poor old father in his lonely home, Edith, my pet?"

She could not speak; she could only answer with her kisses and her tears. Oh, why must she part with either of the parents she so dearly loved? Why had they so forgotten their vows to love and cherish each other to life's end? Why could they not bear and forbear, forgive and forget?

But another step was heard approaching, and the girl started, flushed and trembled at the sound. Her father released her, and moved away; then she found Cecil's arm around her waist, her hand held fast in his.

"Edith, Edith, what is this I hear? Your father and mother separating, and you going with your mother and brother to seek a home in a foreign land? No, no, you are mine; you have promised; you must stay and become my wife at once."

"I cannot, Cecil, my mother needs me; she is feeble and ill, and there is no one else to attend to her wants."

"Nelson must provide some one, since he has seen fit to make all this mischief. You are mine, and I shall not give you up."

"Cecil, I give you up," she answered, in a voice of agony; "you are free."

"And why, pray? What have I done to merit dismissal?" he asked, with some hauteur.

"Nothing, nothing; but -- but I must cleave to my poor, suffering mother; and -- "

"She may be better soon; or she may -- be taken away. Edith, I will wait."

"No, Cecil, I release you; she may live for many years, and I -- shall grow old; perhaps die first. No, you must be free. I shall consider you so whether you agree to it or not."

"Edith, I will not accept my freedom. I cannot and will not give you up. I don't release you."

"I do not ask. I do not want it, Cecil. You know I can never care for anyone else."

"Then why give me up, as if you were tired of me?"

She made no answer; her heart seemed like to break.

He lingered at her side till a late hour. Then they parted in bitter grief, not unmingled with anger on his part, in deep sorrow on hers.

A week later there was another and sadder farewell between them on the deck of the vessel that was to carry Mrs. Delano and her son and daughter to Europe. Called to resign father, lover and native land, what wonder if Edith's brave, true heart almost fainted within her?

CHAPTER III.

SUNSHINE AT LAST.

For the last few years Edith's portion was all their living, Nelson having dissipated the rest at the gaming table and kindred places of resort. What years of trial those were to the poor girl! Nelson would have taken the last cent from her and her mother -- whose weakened mind made her a mere tool in his hands -- but for that mother's sake, to keep her from want and supply her with comforts, Edith set her face like a flint, and refused to lay a finger upon that which was rightfully her own. In vain he tried persuasions, promises, threats and abuse -- even going so far as to strike her, and influencing their mother to do likewise. Edith bore it all with the heroism of a martyr, nor once faltered in her filial love and devotion till death came to give her a sad release.

On the deck of an ocean steamer sat a lady dressed in deep mourning. She sat apart, alone in a crowd. Very lonely and sad was the mourner's heart, and a tear was slowly coursing its way down her cheek when a soft little hand laid itself upon hers, and a sweet baby voice asked:

"Why lady cry? Shall Lulu kiss you and make you well?"

A pleasant though sorrowful smile flitted over the lady's features; for the little face uplifted to hers was very winsome, with its fair, open brow, rosy cheeks, liquid blue eyes full of tender sympathy, and rich red lips held so temptingly near her own as she stooped to take and return the offered caress.

"Bless you, you little darling!" she murmured, lifting the child into her lap. "Ah, if you were mine I should not be so lonely and desolate!" and folding the little form in her arms, she kissed again and again the soft cheeks, ruby lips, and the beautiful ringlets of pale gold that adorned the pretty head.

The babe was full of sweet, childish prattle, and seemed in no haste to be gone; nor did the lady show any desire to part company with her.

"Papa!" cried the child, at length, while the same instant a pleasant, manly voice, close at hand, asked:

"Ah, has papa's pet found a new friend?"

The lady started at the sound, turned her face toward him, and as their eyes met there was a sudden, warm grasping of hands, and a simultaneous exclamation, "Edith!" "Cecil!"

Oh, what a rush of memories, both sweet and sorrowful, swept over Edith's heart as he stood there at her side, holding her hand as if he would never let it go. He still kept it fast in his while he made room for himself and sat down beside her.

"My poor, poor Edith! do I find you here alone and friendless?" he said, tenderly, pityingly.

"Yes, I have left my dear mother at rest in a strange land," she answered, struggling with her tears; "but she sleeps sweetly and will not miss my care."

"And Nelson?"

"I have not seen or heard of him for many months."

"You are going home?"

"To America? Yes."

"Ah, I remember: your father is not living."

"No, she replied, "and the old place passed out of his hands years ago. He sold it and went to live with one of my brothers; the one with whom I expect to find a home for the present."

"Edith, why did you never answer my letters?"

"I never received any -- though I wrote several to you."

"Is it possible? Why, I wrote again and again, but no answer ever came."

"Papa, take Lulu." The little one's hands were outstretched to him.

Releasing Edith, he lifted the child to his knee and folded her in his arms.

A look of pain was on Edith's features as he turned to her again.

"Do not blame me," he whispered; "I waited eight years, not hearing a word from you; then I married, and in little more that a year my wife died, leaving me alone but for this darling of my heart." And he pressed his lips softly to the baby's cheek.

"I could have no right to blame since I had released you," she answered, gently.

The vessel had scarce yet reached the open sea; the whole voyage lay before them, and every day and almost all day long those two were to be seen seated side by side or pacing the dock in company. The little child drew them together, yet still more the old love that had never died out of either heart.

They were nearing port; if all went well, the next day would find them treading their native soil. These two hearts were growing heavy at the thought of parting, though but for a time, and bound together by renewed vows.

"Edith," whispered Cecil, "let me take you at once to my -- our home. Why should I not? We have already waited twelve years."

His look was imploring; her answering one startled and inquiring.

"There are ministers on board; there is nothing to hinder," he continued, bending eagerly over her. "Oh, Edith, be good and merciful! I fear to lose sight of you; I want the right to care for and protect you."

One moment of silent struggling with herself, and Edith's hand was placed calmly and confidingly in his.

With a glad light shining in his eyes he arose, drew the hand within his arm and led her to the farther end of the saloon [sic] where a gray-haired clergyman sat quietly reading.

There must have been some secret understanding between the two gentlemen; for instantly closing his book, and merely exchanging a glance with Cecil, the minister arose, and at once began the marriage ceremony, to the no small astonishment of the lookers on.

"I pronounce you husband and wife." All the rest of that day these words were making sweet music in Edith's heart. She was no longer a solitary pilgrim on life's journey. Nor had her noble sacrifice failed of its reward; for the trials through which they had passed in those long years of separation, had exerted a refining and elevating influence upon both these souls, rendering them more worthy of each other than ever before. They were supremely happy in their union, and Edith's return to her native shores was a home-coming indeed.

Please do not use on other pages without permission.