Copyright 2019 by Deidre Johnson . Please do not reproduce without permission

One of a handful of mother-daughter combinations for series authorship was that of Sarah Leaming Barrow Holly and her mother, Fanny Barrow, better known under her pseudonym "Aunt Fanny." Theirs was a relationship instrumental to Sarah's success: she initially broke into publishing via inclusion in her mother's books, then under the pseudonym "Aunt Fanny's Daughter," before writing briefly under her own name.

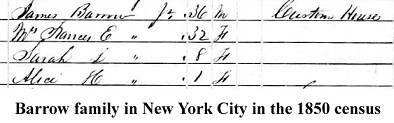

Sarah was born on November 25, 1842, in New York City, the daughter of author Frances Mease Barrow (1817-1894) and James Barrow, Jr. (1813-1868). [1] Her younger sister, Alice Isabel, was born seven years later. Sarah's parents appear to have faced some financial challenges during her childhood (which may have motivated her mother's decision to write).

Fanny sometimes included autobiographical material in her books and drew on her children for inspiration; consequently, Sarah appears in several of her stories. She may have made her first appearance in Fanny's earliest identified publication, Aunt Fanny's Christmas Stories (D. Appleton and Co., 1848). Its first story, "The Christmas Party," is essentially an account of a family Christmas, focusing heavily on a young child named Sarah. [2]

Sarah's publishing debut -- albeit an uncredited one – came in 1858, in her mother's Life Among the Children (sometimes erroneously attributed to Frances Dana Gage, another author who wrote as Aunt Fanny), issued by the short-lived firm Stanford & Delisser. The book contained a collection of stories, and Sarah's is one of the few displaying recognizable autobiographical elements. Aunt Mary: A Sketch by a Girl of Fifteen" is a description of Sarah's great-aunt, Mary Sheldon Graham (1783-1867); its most noteworthy element is a scene depicting Sarah's cousin, little "Stanny" -- Stanford White (1853-1906) - at about age three. Fanny was apparently charmed by the piece, for she included it in another collection several years later, this time with a note acknowledging it was by her (unnamed) daughter. [3]

Even when Sarah was not contributing to her mother's books, she was still sometimes providing material for stories. Fanny's other title for 1858, Nightcaps, served to launch her first series, Nightcaps (6 vols., 1858-60). Like most of Fanny's books, it was a collection of short, generally unrelated stories. The second tale in the book, "The Doctor," tells of Sarah and her younger sister Alice: Alice borrows her mother's scissors and operates on one of her dolls, cutting off its nose -- much to Sarah and Fanny's amusement as they watch silently. [4] Subsequent volumes in the series continued to include occasional tales about, alluding to, or even by, Fanny's own children. In those accounts, Alice was often depicted as an innocent child, while Sarah was portrayed as much older, more of a companion or confidante for her mother. [5]

The Nightcaps series' fifth volume, Big Nightcap Letters, featured more of Sarah's work, though she did not receive credit on the title page. The introductory frame story noted that Sarah, "now a young lady," had "written a story on purpose," and her "The Little White Angel" led off the collection. Fanny's introductory comments described Sarah's technique as "endeavor[ing] to imitate the beautiful German style," a rather different tone from the usual Nightcap stories. Big Nightcap Letters also contained a second story by Sarah, "The Rose Crown." Again, Fanny provided an introduction for the tale, stating, "I have asked Sarah . . . to write me another story after the German fashion," adding that it "was suggested by reading about Christmas in Germany, in Bayard Taylor's 'Views Afoot.'"

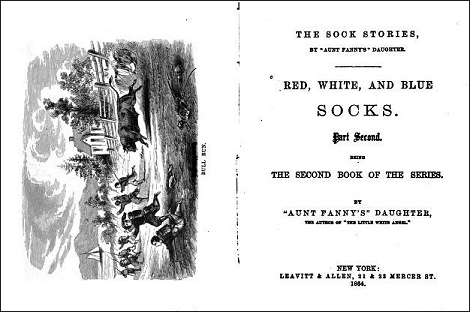

Two years later, capitalizing not only on her mother's name but also on her mother's most recent series, Mittens (6 vols., 1862-63), Sarah started her own series, Socks (6 vols., 1862), under the pseudonym "Aunt Fanny's Daughter." Fanny helped initiate the series by writing the introduction to the first volume, reminding readers that they had met Sarah in the story "The Doctor" in Nightcaps, and the title pages heralded Sarah as "The author of 'The Little White Angel'." ("Angel" had gained additional circulation when it was published -- anonymously -- in both The Independent and Youth's Companion in 1861.) [6]

Fanny's Mittens series had incorporated stories about the Civil War (in which her brother was fighting), and, like her mother, Sarah also acknowledged the ongoing conflict. The series' first two volumes, Red, White, and Blue Socks, Part First and Red, White, and Blue Socks, Part Second, were actually one long story about a group of boys, the Dashahed Zouaves, playing war games. In the third volume, German Socks, Sarah returned to a favorite form with a collection of short stories in a style similar to that of "Little White Angel"; the remaining three volumes were also story collections, with the last set in New York City and containing some autobiographical elements

Sarah's book dedications give a few glimpses of her life and personality. Like her mother, depicts her sister Alice as "little": the series' third volume was dedicated "to my little sister's friend" -- even though the adjective was unnecessary since Sarah had only one sister. If the fourth volume's dedication is to Alice, it further infantilizes her as "darling little Allie Baby." The first volume briefly alluded to Sarah's past: it was dedicated to (the unidentified) "little Cooley and George" with the added note, "I am afraid your pretty curly heads will hardly retain a recollection of a little personage who once lived close to your beautiful home on Staten Island." The series' final volume, Neighbor Nelly Socks, was dedicated to her father; she refers to his "kindly and charming ways with the 'little folk'," noting that they were reflected in "the character of 'Neighbor Oldbird'" in the book. (Oldbird, who occasionally serves as narrator, befriends the local children, buying them candy and toys.) None of the volumes are dedicated to Fanny -- or even acknowledge her role in the publication process.

After the Socks series, Sarah, ceased publishing for a time, turning her attention to family matters. On June 6, 1865, she married architect and author Henry Hudson Holly (1834-92). Born in New York as the son of a "prosperous merchant," Hudson had studied architecture at home and in England, opening an office in New York in 1857; [7] the following year he was "unanimously elected" to the American Institute of Architects. [8] His first book, Holly's Country Seats, was published in 1863; the introduction noted the work had been "fully prepared for the press some two years since" but was postponed by the outbreak of the war. [9] After her marriage, Sarah may have spent more time away from the city and her mother: city directories indicate that while Holly maintained an office in New York at 111 Broadway, he also had a home in Connecticut. The couple's first son, Norman, was born in New York on April 7, 1868. [10] That same year Sarah's parents and sister traveled to Europe, and where her father, suffering from consumption, died in Pau that November. [11]

For the last half of the 1860s, Sarah may have been occupied with her growing family. Only one or two additional publications of hers have been identified from those years: "Forgotten" by "Aunt Fanny’s Daughter" ran in Demorest's Monthly Magazine in 1868; "The Flowers on the Grave," another story in the German style, appeared in Demorest's Young America in 1869.

On October 23, 1870, Sarah gave birth to her second son, John Arthur (sometimes shown as Arthur John), and on September 21, 1872, to a daughter, her own little Alice. [12] About this time, Sarah abandoned the pseudonym Aunt Fanny's Daughter, publishing instead as Mrs. H. Hudson Holly or as Mrs. S. B. Holly. In 1873, two of her children's stories ran in Christian Union (which was also publishing her mother's work) under the name Mrs. H. Hudson Holly; both featured little girls as protagonists. Two more stories, this time about mischief-making children -- one tale purportedly autobiographical -- appeared in Christian Union and St. Nicholas in 1875, and one of her last identified publications, the poem "You and I," ran in Christian Union on May 10, 1876. [13]

The 1880 census records Sarah and Hudson, Sarah's younger sister Alice and Alice's husband Theodore Connoly (1846-1913), all sharing Fanny's home at 30 East 35th Street, along with six boarders and three servants. [14]

Sarah's last series was co-authored with her mother. The Twelve Sisters or Twelve Little Sisters series was issued in 1881 by D. & J. Sadlier, a publisher who specialized in Catholic literature. [15] The series title reflected the number of volumes in the set, each of which bore a girl's name -- Agnes Book, Teresa's Book, Mary's Book, etc. One of the few reviews of the series appeared in the New York Times (which by then regularly recognized Fanny's activities); although the tone is apparently intended to be favorable, it's doubtful the remarks encouraged many sales. After praising the books' old-fashioned look with "rough but good woodcuts," the reviewer made one vague comment about their content -- "big type, poetical extracts, and play-room stories" -- and concluded with the rather odd observation, "Each of the 12 small volumes is dedicated to some little girl with a not unusual name, so that each can be given as a present to a different child." [16] Although the series was published in the United States and England, no copies appear to have been preserved in American libraries and only one set in England, suggesting very limited circulation.

While not a commercial success, the Twelve Little Sisters series is significant in signaling changes in Sarah's life and showing Fanny's support for her daughter. Although Fanny enjoyed increased media attention after the mid1870s, Sarah appears to have avoided it or been overlooked, and one of the only sources of information about her life is a family history that is not completely reliable. That account states Sarah converted to Catholicism in 1878 and (presumably some time thereafter) "[o]wing to her husband's lack of sympathy, the family was broken up." [17] Norman and Alice stayed with Sarah; Arthur, with Hudson. The Twelve Sisters series, Sarah's last known publication, verifies her commitment to Catholicism by 1880, though it remains difficult to pinpoint the date at which the couple separated. The 1880 census lists Hudson twice -- once with the rest of Fanny's family in New York and again as a solitary boarder (marital status single) in Orange, New Jersey. Arthur is with Hudson's relatives in Stamford, Connecticut, and the other two children have not been located. [18] By 1882, New York City directories indicate Hudson had given up his Connecticut home in favor of one in New Jersey, but it is not until 1888 that Sarah acquires her own listing in the directory, a clear indication that the couple had separated by that point. It is possible the division had occurred earlier: family histories indicate that Norman converted to Catholicism in 1886, and other sources note that Alice (who would later enter a convent) had "cherished the intention of a monastic life since her childhood." [19]

Sarah stopped writing after the Twelve Sisters series. She was still apparently living with her mother, who began experiencing problems with her health in the 1890s. On March 4, 1894, a report in the New York Times on the "fashionable audience gathered in Mrs. James Barrow's drawing room" for a guest lecture in a series on "The Old Masters" noted that "Mrs. Theodore M. Connelly [sic] and Mrs. Holly received in the place of their mother . . . who was ill." [20] Two months later, on May 7, 1894, Frances Barrow died. Her obituary noted in passing that one of her daughters, Mrs. S. L. Holly, was "living in England." [21]

That brief statement masked much of Sarah and her children's history in the intervening years. When Fanny died, Sarah was apparently not only living in England but also in a convent, a fervent devotion to Catholicism mirrored by two of her children. The rift in the family caused by her religion appears to have been complete -- and acrimonious. In summer 1891, Harper's Bazaar and the New York papers reported that Sarah's youngest daughter Alice had "entered upon her novitiate as a nun in the Order of St. Dominic, in the monastery of Corpus Christi, at Hunts Point." [22] Alice's father Hudson is never mentioned in the articles. In September 1892, when Hudson died from injuries incurred in a fall three years earlier, his New York Times obituary stated that "[h]e leaves one son" -- thus erasing Sarah and the two siblings who had remained with her. [23]

Both of the children who stayed with Sarah took holy orders, though Sarah apparently did not. A family history asserts that "she entered the novitiate at St. Dominic's Priory . . . at Stone, Staffordshire, England, but left it six weeks later on hearing of her mother's death . . . and returned" to New York. [24] (If that is accurate, Sarah had sailed for England very soon after hostessing the March 4 event at Fanny's.)

According to her son Norman, Sarah "was never a professed nun," only "a devout tertiary of St. Dominic"; he explained that from about the time Alice entered Corpus Christi, Sarah "recited the Dominican Breviary office in Latin every day." [25] At some point, Sarah also appears to have added Catherine to her name, for she filed a passport application as Sarah Catherine Holly. [26] In July 1896, she left New York for Fribourg, Switzerland, where Norman was "study[ing] for the priesthood," and, he told a relative, "thenceforth we lived together or near one another." [27] During the next few years, Sarah and Norman spent time in Italy, France and England, but Sarah "gradually lost her health and developed a sort of paralysis." She probably returned to the United States about 1904, for family histories indicate that Norman "obtained a curacy in New York" in May 1904, for "about a year," and an account of St. Joseph's Seminary, Dunwoodie, New York, notes that he was Director of Liturgical Music there for the academic year 1905-06. [28] During that year, Norman published his only book, Elementary Grammar of Gregorian Chant (1905). Sarah lived long enough to see it in print, and "died in a private hospital in Summit, N. J." on July 8, 1906. [29] No obituaries have been located in the New York or New Jersey papers. [30]

Sarah's start in publishing was atypical for girls' series authors: although some of her nineteenth-century counterparts had relatives who were also established authors, Sarah appears to be the only one whose initial publications and series books were so closely tied to her mother's work. The relative obscurity in which Sarah spent her later years, however, was all too typical of others like her, who wrote briefly for children and then disappeared.

For a longer version of this paper combining Sarah and Frances Barrows' biographies, see Deidre A. Johnson, "Everything is Relative: Frances Elizabeth Mease Barrow (Aunt Fanny) and Sarah Leaming Barrow Holly (Aunt Fanny's Daughter)," Digital Commons@West Chester University.

1. Helen Graham Carpenter, The Reverend John Graham of Woodbury, Connecticut and His Descendants (Chicago: The Monastery Hill Press, 1942): 285, HeritageQuest, gives Sarah's birthdate date as August 15, 1842 (286); the November date appears in church records (Trinity Church [Parish] Registers: Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials from 1750, [Sarah Catherine Holly]) and on Sarah's passport application (U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, Emergency Passport Applications (Passports Issued Abroad), 1877-1907; Microfilm Serial: M1834;Roll #54, [1897-1899 > Volume 106: Switzerland > 574], Ancestry.com).

2. The book is often given a later publication date, but a notice of its publication appears in the Alexandria [VA] Gazette, Dec 18, 1848: 2, America's Historical Newspapers. About 1850, D. Appleton and Co. reissued the book with a less seasonal title, Aunt Fanny's Story Book for Little Boys and Girls.

In the story, Sarah is the only child of the youngest of three siblings, all of whom have gathered at their parents' home for the holiday. Although information is sparse, genealogical records suggest that James Barrow was one of three children. His older sister had at least two children, William and Frances; in the story, two of the children of the daughter of the family are named Willy and Franny.

3. Information about Sarah's great-aunt is from Graham 279. The story appears on pages 109-114 of Life Among the Children and again on pages 69-74 of More Mittens (which, as Fanny implies in the introduction, reprints most of the material from Children). Fanny also included "Aunt Mary: A Sketch, By a Girl of Fifteen" as part of her novel The Wife's Stratagem (Appleton, 1862), adding in a footnote that "it was written by [the author's] daughter at the age mentioned above" (169-74).

4. The story title actually refers to Sarah; in the first half of the tale she acts as doctor for Alice's dolls.

5. Even when Alice and Sarah were not identified as such, the characterization of a childish younger sister and mature older sibling persisted, as in the fourth volume, Little Nightcap Letters (Appleton, 1860). Dedicated "to my daughter, 'Little Alice,'" Letters features two girls, "little Bella" and "Edith, her elder sister," whose mother must travel to the South for several months to regain her health. Throughout the tale, Edith serves as a surrogate parent, even reading their mother's letters aloud to Bella (so that she is essentially speaking in her mother's voice).

6. The story appeared in Youth's Companion 35 (May 9, 1861): 73, and The Independent 13 (Oct. 3, 1861): 6. Several months later The Independent carried a note stating "The beautiful story called the Little White Angel, published some time ago in our columns, was written by Miss Sarah Barrow of this city" (The Independent14 [Feb. 16, 1862]: 4, American Periodicals Series).

7. George B. Tatum, "Introduction to the Dover Edition," Holly's Picturesque Country Seats: A Complete Reprint of the 1863 Classic (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1993): x-xi, and Michael Tomlan, "Introduction," Country Seats and Modern Dwellings: Two Victorian Domestic Architectural Stylebooks by Henry Hudson Holly (Watkins Glen, NY: Library of Victorian Culture, 1976): n.p. Though some genealogies suggest Hudson's birthplace was in Connecticut, Tatum notes Holly's Modern Dwellings states he was a native of New York (Tatum, iii, xiv n2). Holly describes himself as "born and bred in New York" (H. Hudson Holly, Modern Dwellings in Town and Country [New York: Harper & Brothers, 1878]: 152, Google Books).

8. Tomlan, n.p. , Tomlan also notes that Hudson "was probably its youngest member at that time."

9. Henry Hudson Holly, Holly's Country Seats (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1863): v, Google Books.

10 [Norman Holly passport application, September 25, 1895], Passport Applications, 1795-1905, Roll 454 - 01 Sep 1895-30 Sep 1895; [Norman Holly passport application, 1909], National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington D.C.; Passport Applications, Jan. 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925; Microfilm Serial: M1490;Roll #90, Certificates: 9958-10921, 25 Jun 1909-07 Jul 1909 > 506; both U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, Ancestry.com.

11. "Died," [obituary James Barrow], New York Times, Dec. 4, 1868: 5, ProQuest Historical Newspapers. "Barrow, Frances Elizabeth," The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, vol 4 (New York: James T. White, 1902): 556; Carpenter 286. James may be buried in "the Protestant Cemetery, Pau, "though the source of that information also erroneously dates the trip to Europe as 1869 and James' death to 1871 (Carpenter 286).

Interestingly, one of the pieces Fanny wrote for Galaxy while she was abroad was a sketch of Monsignore Capel. Perhaps presciently, much of it centers on Capel's "almost irresistible personal magnetism" which he used to "[convert] a number of English and American women of rank, wealth, and fashion" to Catholicism. (Fanny Barrow, "Monsignore Capel," The Galaxy 10 (1870): 677-78, American Periodicals Series.) During the next decade. Sarah's marriage would fracture on just such an issue.

12. Carpenter 287. The name of Sarah's younger son appears as Arthur John in Carpenter, but it may actually be John Arthur. Unless he changed it prior to entering college, it appears as John Arthur in his fraternity records (Seventy-Five Years of IKA, 1829-1904 [New York: N.p., 1905]: 34, Google Books); in Columbia College's Register of Officers and Students 1892-93 ([New York: 1893]: 92, Google Books), and again (as John Arthur Holley) on a ship's passenger list from 1927 (New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, Year: 1927; Microfilm Serial: T715; Microfilm Roll: T715_4036; Line: 7; Page Number: 158.[1927 > April > 12 > Essequibo > 17] , Ancestry.com.)

13. The publications were Mrs. H. Hudson Holly, "The End of the Rainbow," Christian Union 7 (Jan. 22, 1873): 76ff; Mrs. H. Hudson Holly, "Polly," Christian Union 7 (April 30, 1873): 356ff; Mrs. S. B. Holly, "A Dreadful Darling," Christian Union 11 (March 10, 1875): 213; Mrs. H. Hudson Holly, "Tom's Deluge," St. Nicholas 2 (July 1875): 556ff; Mrs. S. B. Holly, "You and I," Christian Union 13 (May 10, 1876): 381, all American Periodicals Series.

14. The inclusion of Hudson Holly in Fanny's household may be an error or the family's attempt to preserve the appearance that Sarah and Hudson were still together. It seems unlikely that he provided the information, since the information about his and his parents' birthplace is completely inaccurate (all are listed as having been born in Massachusetts); moreover, Hudson also appears in another census entry, as a boarder at a hotel in East Orange, New Jersey. The information there about birthplace is correct, though there is no listing for occupation -- and his marital status is shown as single (1880 United States Federal Census, Orange, Essex, New Jersey; Roll: 780; Family History Film: 1254780; Page: 90C; Enumeration District: 106; Image: 0636, Ancestry.com).

15. John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United States, vol. 1 (New York: R. R. Bowker, 1972): 526.

16. "New Books," New York Times, July 17, 1881: 10, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

17. Carpenter 286. Although Carpenter's The Reverend John Graham of Woodbury, Connecticut and His Descendants is invaluable in providing details about the family, it also contains a number of errors. (For example, dates for several events -- such as Sarah Barrow's birth or James Barrow's death -- conflict with those in official documents.) Sarah's son Norman appears to be the source of some information about the family, but is not specifically identified in relation to anything pertaining to Hudson or the marriage.

18. [Arthur Holly in Chas. A. Hawley household], 1880 United States Federal Census, Tenth Census of the United States, 1880, Stamford, Fairfield, Connecticut; Roll: 96; Family History Film: 1254096; Page: 299B; Enumeration District: 152; Image: 0599, Ancestry.com.

19. Carpenter 287; "Personal," Harper's Bazaar 24 (1891): 587, American Periodicals Series.

20. "The Social World," New York Times, March 4, 1894,: 13, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

21. "'Aunt Fanny' Dead: The Well-Known Juvenile Writer Expires from Old Age." [New York] Evening World, May 8, 1894: 5, Chronicling America.

22. Quoted material from "Personal," Harper's Bazaar. See also "Miss Holly Becomes a Nun," New York Times, July 3, 1891: 3, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

23. "Henry Hudson Holly" [obituary], New York Times, September 7, 1892: 5, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Hudson Holly's will shows his feelings even more clearly. Sarah is never mentioned. Everything is left to his son, John Arthur, and, in the event of his son's death, to nieces and nephews. Hudson even took the time to add, "My daughter Alice Louise never having been under my control and circumstances being that she has never been to me as a daughter I give her nothing." His initial will from March 1891 also included the statement, "My son Norman not having acted in accordance with my wishes I give him nothing." A later version from October 1891 adds a codicil with more detail (and perhaps an additional insight into Holly's thoughts about family): "My son Norman having been supported and educated by me until he arrived at the age of twenty-one years and having elected a position in which he can never expect to make any return to me should circumstances so direct, his own sense of honor would naturally suggest that he should not receive anything or very little from my estate, I therefore direct my executors to pay him one hundred dollars out of my estate. I do this from no want of love and affection which I bear to him, but simply for the reasons above stated." [Hudson Holly, New York Wills, Vol 0482-0484, 1892-1893, Ancestry.com]

24. Carpenter 286.

25. Ibid.

26. [Sarah Catherine Holly], U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925. The passport is dated 1896, but she may have adopted the name much earlier, for the 1888 city directory lists her as "Sarah C."

27. Carpenter 286. Norman's ordination was in 1898, in Rome. Material in the next sentence is also from this source.

28. Carpenter 286; Arthur J. Scanlan, St. Joseph's Seminary, Dunwoodie, New York 1896-1921 (New York: The United States Catholic Historical Society, 1922): 111, Google Books. Carpenter also states that "Shortly before [Sarah's] death [in July 1906], they traveled in Italy for her health," (286) but it is difficult to determine what period is meant by "shortly."

29. Carpenter 286.

30. The August 22, 1906, New York Times lists Sarah L. Holly's will among those for probate, and legal notices, such as the one from December 3, 1906, in the Times indicate that her brother-in-law, Theodore Connoly, was executor of her estate.