Another series author whose life clearly influenced her work was Mary Bradford

Crowninshield. Born in New York in April 1844 (not Maine, 1854, as erroneously

listed in several reference works), she was the daughter of author Sarah Elizabeth

Bradford (nee Sarah Elizabeth Hopkins, 1818-??) and attorney (later, judge) John

Melancthon Bradford, Jr. (1813-1860). [1] The eldest

daughter and the third of six children, she grew up in a household that included her

maternal grandmother (and, at one point, paternal grandmother) and regular exposure to

books. [2]

Mary's mother began her writing career with children's fiction and later moved to works for adults, a pattern Mary would also follow. Sarah Bradford's first publications, the six-volume Silver Lake Series, were issued under the pseudonym "Cousin Cicely" and appeared in 1852, when Mary was eight. [3] Later, Mary recalled that the Silver Lake Series influenced her decision to write. At age seventeen, she decided to try her hand with the popular sensational fiction of the day and once told an interviewer, "'I wrote [my first] story in one evening and copied it the next day, tried it on the family, who laughed me to scorn' (for indeed it was [a sensational tale] full of chloroform, murder, cliffs, and mystery.) 'but I sent it to the paper and they . . . sent me $15.'" [4]

The first success, however, was followed by the publisher's rejection of her second story, [5] and Mary abandoned the field for twenty-five years. During that time, she may have travelled in Europe with her mother, who went abroad in 1862. [6] In 1870, she was definitely in Germany, for she married naval officer Lt. Cmdr. Arent Schuyler Crowninshield in Dresden on July 27. [7] So far, she has not been located in the 1880 census, which may indicate she was still in Europe. By 1884, at least, she had apparently returned to the United States, for "The Valentine," a song written for her son Caspar, was published then.

In 1886, Mary Crowninshield wrote All among the Lighthouses; or, The Cruise of the Goldenrod, the first volume in her Lighthouse Children series (3 vols., 1886-1889). The story follows several children and their families touring the coast of Maine. One review noted that "The author's husband was for some years a lighthouse inspector, so there can be no question as to the accuracy of the information about buoys, diving-apparatus, etc." The book earned praise not just for the information but also the quality of the writing; the reviewer felt " the chief attraction of the book is the sympathetic sketching of different types of character, and the picturesque description not only of the scenery but also of the life on the Maine coast." [8]

The second volume, The Ignoramuses, A Travel Story

was published the following year, this time taking the characters through Switzerland.

Again it earned praise; one reviewer called it "vastly superior to compilations like the

Knox or Champney books." [9] The book's

dedication suggests Crowninshield based it on her own experiences, for it is addressed to

"those whose joyous voices have gaily answered mine as together on early frosty autumn

mornings we climbed the pathway which led us to the summit of the Uetliberg" and "those

in whose dear company I have passed the quiet weeks among the upper alms,

or crossed the glacier crevasses."

The second volume, The Ignoramuses, A Travel Story

was published the following year, this time taking the characters through Switzerland.

Again it earned praise; one reviewer called it "vastly superior to compilations like the

Knox or Champney books." [9] The book's

dedication suggests Crowninshield based it on her own experiences, for it is addressed to

"those whose joyous voices have gaily answered mine as together on early frosty autumn

mornings we climbed the pathway which led us to the summit of the Uetliberg" and "those

in whose dear company I have passed the quiet weeks among the upper alms,

or crossed the glacier crevasses."

By the time the dedication was written, Crowninshield was in New York; her husband, now with the rank of Commander, was stationed on the school ship St Mary. The third and final volume, The Light-House Children Abroad; or, The Ignoramuses in Europe, was published in 1889.

Travel stories continued to be popular with readers, and Crowninshield remained

with the genre, but shifted audience and region, writing several that probably gained

added sales because of interest generated by the Spanish-American War. In 1898, she

published Latitude 19 Degrees, A Romance of the West Indies in the Year of Our Lord

Eighteen Hundred and Twenty; Being a Faithful Account and True, of the Painful Adventures

of the Skipper, the Bo's'n, the Smith, the Mate, and Cynthia and Where the Trade Wind

Blows: West Indian Tales. One reviewer observed "It is a curious coincidence that

aptain Schuyler Crowninshield should have been the former commander of the Maine [a command

that ended before the war], and that his wife should have written what is perhaps the most

life-like account of the plain people of Cuba. . . . her recent book, 'Where the Trade Winds

Blow' . . . . can hardly fail to be of interest to all Americans at the present time.

The homes of the characters of her book are those which have since been laid in ashes by

the Spaniards."[10]

Travel stories continued to be popular with readers, and Crowninshield remained

with the genre, but shifted audience and region, writing several that probably gained

added sales because of interest generated by the Spanish-American War. In 1898, she

published Latitude 19 Degrees, A Romance of the West Indies in the Year of Our Lord

Eighteen Hundred and Twenty; Being a Faithful Account and True, of the Painful Adventures

of the Skipper, the Bo's'n, the Smith, the Mate, and Cynthia and Where the Trade Wind

Blows: West Indian Tales. One reviewer observed "It is a curious coincidence that

aptain Schuyler Crowninshield should have been the former commander of the Maine [a command

that ended before the war], and that his wife should have written what is perhaps the most

life-like account of the plain people of Cuba. . . . her recent book, 'Where the Trade Winds

Blow' . . . . can hardly fail to be of interest to all Americans at the present time.

The homes of the characters of her book are those which have since been laid in ashes by

the Spaniards."[10]

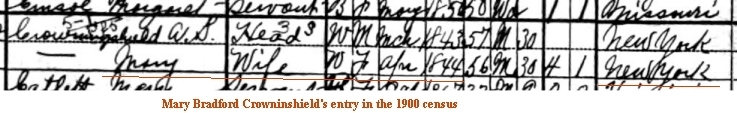

By 1900, the couple were living in Washington, D.C., at 820 18th St NW. The census indicates they had had four children, only one of whom was still living, and that the household included a butler, cook, and servant. Mary continued to write, and that year's novel, The Archbishop and the Lady, went through several editions.[ 11] Her husband was now a Rear-Admiral and Chief of the Bureau of Navigation. After his retirement in 1903, the couple kept their home in Washington, D.C., but also spent time traveling abroad. They went to Italy in December 1905 to visit their son Caspar, who was United States Consul in Castlemari (causing Mary to miss the performance of her first play, "Between Two Fires," at the Lyceum in New York). Mary was still in Castlemari in April 1906 when Vesuvius erupted, and she described the scenes at length for the New York Times. [12]

Rear Admiral Crowninshield died May 27, 1908, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Some time afterward, Mary relocated to Rochester, New York, where her mother was living. [13] She was in the New England Sanatorium in Melrose, Massachusetts, when she died on October 14, 1913. She is also buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

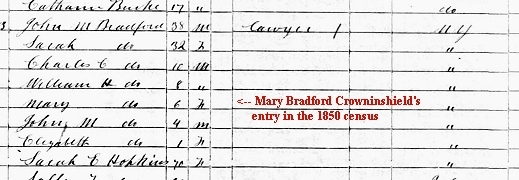

1. The Dictionary of North American Authors Deceased before 1950 gives Mary Crowninshield's birthdate and place as 1854, Maine; American Authors and Book, 1640 to the Present Day repeats the 1854 date. The 1850 census, however, already includes Mary, age 6, and she is shown as being 16 in the 1860 census; moreover, the 1900 census gives April 1844 as the month and year of her birth. All three records show New York as her birthplace.

Information about Mary's parents is from Benjamin Woodbridge Dwight, The Descendants of John Wright, of Dedham, Mass. J. F. Trow & Son, 1874: 1096-97, and from James A. McGowan's "Harriet Tubman According to Sarah Bradford," Harriet Tubman Journal (April 2004). McGowan's essay includes not only biographical information about Bradford but also a detailed criticism of both editions of her biography of Tubman, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman and Harriet Tubman, the Moses of her People The latter is also online at Documenting the American South.

2. The 1850 census shows six-year-old Mary had two older brothers, Charles, age 10, and William, age 8, as well as a younger brother John (age 4) and baby sister Elizabeth (age 1); the youngest child, Louisa, was born five years after Elizabeth. Mary's maternal grandmother, Sarah Elizabeth Hopkins, is part of the household in the census records for 1850 and 1860, suggesting she was a permanent resident. The 1850 census also lists 20-year-old Sally Taylor and 17-year-old Thresa Gustine [?], whose role in the household was not recorded, but who may have been servants; the family had two servants for the 1860 census. At that point, the family appears to have been living with Mary's paternal grandmother, Mary Bradford.

3. Although called a series, the books are actually collections of short stories and poems, rather than material linked by continuing characters or situations. Three of them, The Old Portfolio: a Collection of Pieces in Prose and Rhyme, for the Silver Lake Stories (volume 2), Green Satchel: a Collection of Pieces in Prose and Rhyme, for the Silver Lake stories (volume 3), and Aunt Patty's Mirror: a Collection of Pieces in Prose and Rhyme, for the Silver Lake stories (volume 6) are online at the State University System of Florida's PALMM Project.

4. "Books and Authors," New York Times March 30, 1901: BR2. p> 5. Ibid.

6. McGowan.

7. "Burial in Washington" [obituary for Mary Crowninshield], Boston Daily Globe, Oct 17, 1913: 11, gives the wedding date; the sheet music for "Valentine" is online at the Library of Congress's American Memory website.

8. Griswold, W. M. A Descriptive List of Books for the Young. Cambridge Mass.: W. M. Griswold, 1895: 92.

9. Ibid.

10. Daily Picayune [New Orleans], Apr 27, 1898: 4.

11. The Archbishop and the Lady is also available online via Google Books.

12. "Heard in the Foyer," New York Times, Dec. 24, 1905; Mrs. Schulyer Crowninshield, "The Last Days of Bosco Tre Case," New York Times, April 29, 1906.

13. Sarah Elizabeth Hopkins Bradford's date of death is not known, but she appears in the 1900 and 1910 census in Rochester, New York (in both, boarding at 37 S. Washington St.).

14. Arent S. Crowninshield, Arlington National Cemetery Website.