Copyright 2010 by Deidre Johnson . Please do not reproduce without permission

CHAPTER V

IT is needless to open this chapter by saying that Robby was delighted with his skates. He tried them, and found them to fit well, and to answer his purpose excellently. Of course he was very happy in the possession of them, but the joy did not make him a worse, but a better boy. He thoroughly resolved that he would give but two evenings in a week to skating, and that in the remaining four he would continue his work on the shoes, and help Nellie all that he could about the Christmas-tree.

So, the second evening after the skates came, he surprised Nellie by sitting down quietly to his work after tea, instead of going out to the skating-pond, as she expected that he would do.

"Why, Robby," she said, "you have not put the new skates away to rust so quick, have you?"

" Oh, no; the skates are not going to spoil, neither is the boy that wears them," Robby replied, with a laugh. "I shall use them again when the time is right for it."

"Why, what do you mean, Robby? there was never a more beautiful evening than this for skating."

"Agreed," said Robby. "It is a lovely evening, too, for binding shoes."

"But don't you think Mr. Brown would be disappointed if he thought you cared so little for his gift as to put it away after one night's sport? "

"I think he would be more disappointed if he thought I was growing into a wickedly selfish boy."

"But are you not going skating anymore?"

"Yes, I told you, when the time comes right for it. But I am resolved that I will give myself only two evenings in a week for skating, and the other evenings I will work with you."

"Shall you be satisfied with only two evenings out, Robby, when all your playmates are taking six?"

"Yes. I will take more comfort than all of them, for the evenings in will be pleasant, when you and I are sewing together, and planning our Christmas work; arid in those two evenings that I am out I will feel so well, that I can crowd more fun into them than the other boys will into six."

This resolution of Robby's was really a delight to Nellie; for, while she had unselfishly told him to go and take his pleasure with the boys out of doors, she was yet very happy to have his company at home, and very, very glad to have the work done which was to bring the money for the' Christmas-tree.

Robby began to be intensely interested in this work for the coming Christmas. He had a large, kind heart, and when it was enlisted in doing good, it moved him to most generous giving, he really enjoyed the work-evenings as much as the play-evenings, for there were so many pleasant plans to make, that it seemed like life in a fairy world. The work progressed rapidly, and the children bound as many pairs of shoes the first week after the new skates came, as they had done any week of the winter, in spite of Robby's taking his two evenings out.

He was unable to understand how that could possibly have been done. But the next week he made the discovery that Nellie had taken to getting up an hour earlier in the morning, and working before he was out of bed.

"What a girl you are, Nellie," he said, as he crept down the staircase one cold morning to find her sitting comfortably by the fire with her little fingers flying back and forth at the work as if her life depended upon their speed. "I guess you are trying to follow tricky Tim's example, ain't you? "

"If you call beginning work early in the morning following Tim's example, I am. But I hope I am not making as bad a use of the morning hours as he did."

"No; I'll warrant you will never be doing any thing as mean. as he did. But I don't consider it quite the fair thing for me to take play hours off while you are putting work hours on to the week.

"What difference does it make, so that the work gets done? "

"I should think it makes a good deal of difference, as you will see from this time on, when I shall be up an hour before day, and at work as well as you."

"Very well, if you like it. I shall be very happy of your company."

"Isn't this the day that we are to pick out the children in the alley that are to be allowed to come to the Christmas-tree ? "

"Yes. I thought that we would go with our finished work to-day, and ask Mr. Dixon, at the factory, to tell us what children in the alley really needed our little gifts most of all.""

"How many children are you going to invite, Nellie ?"

"I don't think I will try more than six. That will be as many as we can manage, I think, with what money we shall have."

"What are you going to buy for their presents? "

"I think we will buy shoes and mittens and comforters, and such things as are really most needed, and will make them remember Christmas longest with gratitude. "We might spend part of our money in toys and candies, and ornaments for the tree, that would make the children very happy on that night. But these things would be soon gone, and the children would be no better off. I remember hearing our minister say once, in a sermon, that every thing that Christ did when he was on the earth was a real blessing to those for whom he labored. Now, I think, if we are going to celebrate Christmas, we ought to do on that day, just as nearly as we can, what Christ would himself be doing if he were on the earth to-day."

"You are always thinking such nice things, Nellie."

"And you are always ready to help me do the nice things that I wish to be doing."

"Shall we have money enough to give some substantial present to each of the six poor children?"

"Yes, I think we shall."

"And to buy the tree, too? "

"Yes; I hope so. We haven't got a very big pile of dollars, it is true, but I think we can make them go a good ways, if we try."

" You wouldn't like to ask Mr. and Mrs. Brown to help us a little, would you? You know that they would be delighted to spare a little for such a work."

" Oh no, Robby. I have no doubt they have a great many plans for spending money on Christmas, and we must not lean upon them any more than we are doing. It wouldn't be half as well for us, either, as it will be to do our work in our own way and with our own means."

"Well, just as you say, Nellie. You always see things clearer than I do when right and wrong are in question."

"I don't know about that. But I do know, .that if we are to do any good to others, and got any for ourselves at the same time, it can only be by working hard and making some sacrifice, in order to make others happy. There wouldn't be much accomplished, if you and I were simply to go and ask Mr. and Mrs. Brown to give some Christmas presents to the poor."

"Why, the poor children would be just as warm in their now mittens and stockings as if you and I had earned every dollar that bought them."

"That's true in one sense, and not true in another. But our own hearts would not be nearly as warm, if we saw some one else give clothing to the poor, as if we gave it ourselves, and gave it as the fruit of our own exertion."

"I know it will do us good, as it always does any one good to act unselfishly. But what do you mean, Nellie, by saying that in one sense the mittens and stockings would not be as good for the poor if they were bought with Mr. Brown's money as if they were bought with ours?"

"I will tell you, Robby. You may laugh at me or not, as you please, for what I am going to say to you; but I believe in 'the laying on of hands.'"

"You are full of mysteries, Nellie. What do you mean by ' the laying on of hands'?"

"I mean that you and I are going to do something more in our Christmas giving than simply earn some money for presents, and go to a shop and buy them after the money is earned."

"I thought that was all that you proposed. What can we do more than that? "

"We will work on the presents ourselves make them with our own hands."

"How can we, Nellie ? "

"I know how to knit mittens and stockings, and I shall teach you."

"Why," said Robby, laughing, "that is a comical idea. I guess the mittens and stockings that I should knit wouldn't compete with those in the market."

"They would, Robby. If they are ever so rough in their construction, they will be the best mittens in the world if yon knit your heart into them."

"How can I do that, Nellie?"

"We shall see. I told you that I believed in the 'laying on of hands.' Christ did that. When He was going to do any good to the poor or the sick, he didn't send some one else to do it. He went himself, and when he had sought these needy ones and found them, he laid his hands on them, and healed and blessed them, as if nothing could be so much to them as the influence of his touch."

"Yes, Nellie, I know. But that seems to me a very different thing. He laid His hands on the people themselves, when he wished, to give them the blessing. It was not on the mittens and stockings that they were to wear."

"I expected you would say that. The world has been saying it for so long, that it has really almost forgotten the teachings of the New Testament about ministering to the poor and needy. People very good Christian people, too give to the poor very much as they would throw a bone to a dog. They have set, fixed, cold plans for charity, and lay by a certain amount of money to give away, just as they would heap up a pile of rocks with which they were to build a tower. I tell you, Robby, that is no way to give to the poor. It is very little blessing we give to them, and very little that we get for ourselves in this way. We must go back to the teaching of the New Testament. In those days they tools handkerchiefs and aprons that had been about the persons of the Apostles, and carried them to the sick. What does that mean, if it be not true that Christians can bless more by giving what has been done by their own hands, than they can by merely handing over some other person's work to the poor?"

"Well, this is really a new idea to me. But I see something in it, and I am quite willing to be taught to knit. I will help your Christmas plan with my whole heart, and as well as I can with my clumsy fingers."

" I love you for the willingness you show in accepting my plans, Robby, and we shall see how happy we will all be when the blessed Christmas time is here."

CHAPTER VI.

WE need not stop to tell of all the happy hours that Nellie and Robby spent in preparation for their Christmas giving.

They selected their six children from Baker's Alley, and though the invitation was not given until a few days before Christmas, according to Mr. Dixon's advice, they yet felt a personal interest in these little waifs, and passed through the alley many more times than was necessary, in order to see the little hands and feet, and judge whether they were the size of the mittens and stockings that were growing in their pleasant room at home.

Robby couldn't quite get over the idea that boughten mittens would be quite as useful to the poor as the ones he was able to knit; especially was this his opinion of those first ones, the thumbs of which looked more like the neck of a squash than they did like a proper encasement of part of a child's hand. But, like a wise boy, he kept saying to himself: "Nellie knows better than I, and I will not bother my head about it if she says it is right. I will accept the praise that she gives me for trying to knit as well as I can, and let the effort go as far as it will toward bringing the blessing."

Christmas came at last, and the array of pretty things that were gathered in the Quinby house, it was really a delight to see. The children had found their money to hold out remarkably in the using. The skill of one's fingers, added to the use of one's pennies, makes a great difference at such a time. Nellie had knit four pairs of stockings and three pairs and a half of mittens; and Robby had knit two pairs of stockings and two pairs and a half of mittens. Of course he did not expect that he could knit as fast as she. Her muscles had been trained to this work from the time they were little fingers, just growing out of babyhood; while his were just taking their first experience in this kind of deft handling of inanimate things.

Yet his delight at looking on the finished work was fully as great, if not greater, than hers. It is such a satisfaction to have accomplished any thing that we had before thought was impossible to us! Robby was tasting this delight to the full. He went, scores of times every day, into the bedroom where these treasures were spread out upon the bed, that he might count them again and again, and think which ones he had knit. He really had the worth of the money many times over in the heart-warmth these articles gave to him.

After the six pairs of stockings and mittens were done, the children found that they had money enough left to pay for the tree, and also to buy some calico for aprons; and, afterward, some toys, candies and candles for the tree's adornment.

Oh, how happy they were when it was brought the day before Christmas, and they had the whole day in which to prepare it for its evening-uses.

Robby was ingenious, and he devised a way to set the tree so that it would bear all its load of gifts without trembling".

Nellie was skilled in all little matters of taste, and she arranged the tree, after it was set, so beautifully that both Mr. and Mrs. Quinby, who were good judges in these matters, thought there could never have been. any thing much more lovely than this work of their children's hands.

The evening came at last, not slowly as it might have done if the children had not been so closely occupied, but tardily enough to have given them time for full preparation before their invited guests arrived,as these guests had been especially told that they were not to come till dark.

Robby had been anxious to invite Mr. and Mrs. Brown to come and see the tree and the poor children; but Nellie had thought it not best. She was afraid that it would seem like boasting of their good works if they told any one what they were doing. So, when the evening came, no one came with it but the. six little dirty, ragged children, for whom the work had all been done.

Nellie had thought about the dirt beforehand, and provided for it. She had plenty of warm water and soap ready, and the first treat that she gave her guests on their arrival was a good thorough washing of hands and face, which was, perhaps, as good a Christmas blessing as she could have given them.

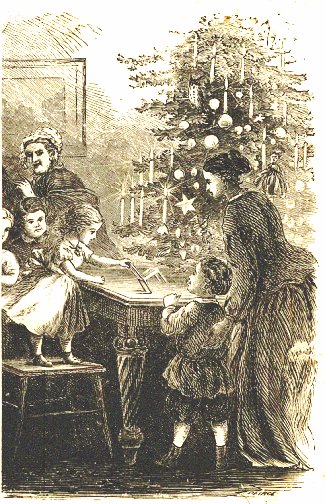

After this process of cleaning was over, they were taken to the room where the loaded and lighted tree stood ready to receive them, and the delight of the hour that followed, it would be difficult to describe. The poor little creatures were really wild with their joy; they danced, and sang, and shouted, and made the house ring with their merry laughter. Then and there they put on the new articles of dress, and a comical sight it was, to witness this process of dressing.

Some of them had never had a stocking on their feet before. Little Tommy Gould put both his feet into one. stocking, and Ellen, his sister, covered her chubby little toes with a mitten.

Peter Prink was determined to try climbing the tree, to reach a large bag of candy that hung near the top, and Robby had to threaten sending him home before he could be quieted.

Mary Grundy tried to eat one of the lighted candles, which she slyly stole from the tree, and, burning her mouth, cried for a moment with the pain.

But these little mishaps were not serious trouble, and really bore no proportion to the joy of the hour.

Every little girl had a new, bright calico tier, and these made them look very neat and pretty.

The candies and oranges did not last as long as Nellie and Robby had intended they should, as it seemed not possible for the little ones to keep them an instant in their hands before they vanished down their eager throats. They had never in all their lives had as much candy before, and it is not to be wondered at that it would not stay outside their little hungry mouths.

Nellie had prepared a nice supper for them, and, after they had seen the last bag of candy, the last present and the last candle off from the tree, they all sat down to the table to eat.

Here they made a very pretty sight. It was a comical sight, as well as pretty, for some of the children could not be persuaded to take their mittens off, and some of them could not keep the feet with the new stockings under the table, but persisted in sticking the little feet up where they could sec them. Every one had the toys belonging to them piled up beside their plates, so that the table was quite loaded down with treasures.

Just as they were seated at table, a knock came at the door, and Robby opened it to find, standing there, a very good-natured looking Santa Claus, with an immense pack on his back.

"Why! why!" said he. "Here is an unexpected visitor."

Without giving him time for farther remarks, Santa Claus sprang through the doorway, and was in the midst of the little group within.

Some of the children were frightened, and cried; but the fright was soon over when they found that the strange-looking old man had more candy, and nuts, and cakes, and oranges, than they could all eat or carry home.

"What? what?" said old Santa. "What does all this mean? I came to this house to give gifts to two children, and here are eight." He opened his pack and took from it some very nice presents for Nellie and Robby. There was the very dress for Nellie that she had seen in a shop window in the town, and wished for very much, but had no thought of sparing the money to buy it. Robby had the fur cap that he had coveted, but had not dreamed that he could possess this winter, and a pair of fur gloves in addition. Then Santa Claus had presents for Mr. and Mrs. Quinby, and numberless little things for the house, which, he said, belonged in common to the family.

While these gifts were being pulled out from the big sack and distributed, they were all so excited over their presents as not to have noticed that

Mr. and Mrs. Brown had quietly followed Santa Claus into the room, and were standing in the shadow of the chimney, watching the merry group.

CHAPTER VII.

THE coming of Mr. and Mrs. Brown to the Christmas festival had been quite without suspicion, on their part, of what was going on in the Quinby house. They had planned their own little surprise for Nellie and Robby, not knowing that other children would be present to help them in the enjoyment of it. But when they came, and found how unselfishly their own dear little adopted boy and girl were spending the Christmas eve, their hearts grew very warm toward them.

After they returned to their own beautiful home, Mrs. Brown said:

"What a lesson I have learned from those children to-night. Who would ever have thought that they, with as little means as they have, could have planned and carried out such a project? "

"It was really very beautiful," Mr. Brown replied; "if they can do so much good with their circumstances, what ought we not to do with ours? "

"I have thought of that," said Mrs. Brown; " and I am sure the best of their good works to-night has not yet been accomplished. It is to live as an example, and we, with every one else that shall know of it, ought to be moved to more earnest, benevolent living, because we have had this opportunity of seeing how much may be done by two children, with no money save what they have earned with their own active brains and willing fingers."

"That is the beauty of their offering on the Lord's altar. It came all from the impulse of their own good hearts. The memory of it should be precious, and should bless and make better all lives connected with it."

"That is the best of all good work, it does not die with the doing. It helps the world by inciting others to go and do likewise," said Mrs. Brown.

"I wonder where they got all those presents. Why, there must have been a tree-full, for every child seemed to have an abundance, both of clothing and toys."

"They earned the money to buy the material for the clothing, and then made all of it with their own hands."

"How do you know?"

"I asked Nellie, and she told me."

"Why, it does not seem as if she could have done as much sewing and knitting as that in a whole year."

"She did not do it all, Robby helped her. He had already learned to sew in binding shoes, and Nellie has taught him to knit since this Christmas work began."

"Well, really they are most remarkable children. Last summer she was doing boy's work out-of-doors, and this winter he is doing girl's work in-doors. I wonder if he did really knit some of those stockings and mittens."

"Yes; Nellie said that he knit nearly half of them."

"Well, that is a boy worth having. That must be the reason that he has not been out more with the boys skating. I asked him the other day if he went out all these moonlight evenings on the ice, and he replied: 'No, sir; not all of them, for I am sometimes busy at home; but I enjoy so much when I do go, that I think I get as much pleasure, on the whole, as those boys do that skate every night.' "

"It has been very noble of these children to give up so much for other children. I love them clearly for it. We must try and cherish them the more, because we see these beautiful traits of character, that may be developed into really helpful service for the world, if God should spare them to grow to manhood and womanhood."

"What can we do more for them than we are doing? "

"I think we ought to show our appreciation of all these beautiful deeds that their kind natures prompt them to do."

"Well, how? "

"By seconding their work every time that we find them engaged in any thing of which we can so wholly approve as we can of this. I have a plan that will help us say in deed what our hearts are saying about this Christmas-tree."

"What is it?"

"We will give them a little surprise at the New Year's time. Let us invite Robby and Nellie here to spend the evening with us, saying nothing in our invitation of any thing more than a quiet evening with us alone. Then let us invite the same little group from Baker's Alley that we met at their house, and have a tree, from which we shall give them presents all round again."

"That will be delightful," said Mr. Brown; " only "

"Well, only what? "

"I hesitate a little about taking such a tribe of little wild Arabs into our house. You know there are so many delicate precious things here, that they can break and destroy. You saw how they acted there to-night."

"Of course you consider, my dear, that these children have never had an hour's teaching, and they cannot help doing what they do until they are taught better. As for the damage that they might do if they were allowed here for an evening, I will try and prevent it as much as possible, by putting away out of their reach all the articles that they could most easily destroy, and for the rest, we must be patient with the mischievous fingers, and put a small bill for repairs into our calculation of the expenses to be incurred by the party."

"Very well. I see that you are quite right in wishing to encourage Robby and Nellie in this way, and I will try, as far as it is possible for me, to help you in the preparation. You are also quite right in saying that we can, and ought to be willing to spare a little money for repairs, in order to help these poor children. It would be a poor use of the luxuries God has given us, to let them make us selfish, so that we should serve Him less, rather than more faithfully because of them."

"I think it would, and so we are to consider it decided that we give the New Year's party? "

"Yes, we will give it, and we will try to make the children as happy as possible."

"This will be a busy week, if we do all that we ought to do to make it a success."

"I don't know about that. The holiday gifts are plenty in the market, and I will furnish you all the money you wish to buy with."

"But, my dear," said Mrs. Brown, "I don't think that the end will be accomplished if we get and give the presents in that way. We certainly should not, in that way, be following the children's example. What touched me most deeply of all, was what Robby told me about their making the presents."

"Ah! what was that? "

"I asked him why they didn't tell us that they wanted money to buy clothing for the poor, and ho said that Nellie would not let him, for two reasons. First, she did not wish to ask us to do more than we are doing for them. But he said, more than that, if Nellie had a hundred dollars to spend in Christmas presents, she would yet urge that they should be made with their own hands."

"Why? I am sure I don't see any sense in that."

"I didn't at first; 'but when he told me what she said, I understood it, and it seemed very beautiful. Nellie says that the New Testament teaching about laying on of hands means something, and that Christ and all his apostles, when they wished to do good, did it with their own hands."

"Well, really ; I never thought of that before. Isn't she a singular girl? She doesn't seem to be trying to do things in other people's ways, but to have ways of her own about every thing."

"It seems to me that in this case she is not trying ways of her own, but is very decidedly following the New Testament ways."

"Yes, she is imitating the Christ. But she certainly has a very original way of doing that."

"I like her way."

"So do I, most decidedly, but her example will not be so very easily fol- lowed. You surely don't propose to teach me to knit and sew in the way she has taught Robby, in order that I may give the Baker-Alley children presents made with my own hands."

"No, we have not time for that between now and New Year's day. But there are some things that you already know how to do, that may be done, and I propose that we each of us resolve that, in addition to the gifts we buy, which I do not intend shall be few or meagre, we shall each, in this coming week, make eight presents for the eight children with our own hands."

Mr. Brown laughed heartily at this suggestion, and said:

"Well, my dear, where will you have me begin? Shall I try making bonnets or dresses or shoes or felt-hats, first? "

"None of these; but you used to be very skillful with your jack-knife, and I think your hand cannot have forgotten all its cunning. You can whittle some toys that will answer Nellie's requirement of work done with your own hands, and I will find something to do with mine for each of the children, and so we. will test, by actual experience, the wisdom and worth of her plan."

"I am agreed," said Mr. 'Brown, laughing merrily; " I think I shall feel quite like a boy again, when I get at work with a jack-knife and a stick."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Now that the plan was laid, both Mr. and Mrs. Brown went into the work heartily, and they both agreed at the end of the week that the last week of the year had been the happiest of all the fifty-two. When New Year's eve came, the array of presents at Mr. Brown's house was worth the seeing, and Mr. and Mrs. Brown were fully as much pleased with them as Robby and Nellie had been with theirs at the Christmas time. Mr. Brown had counted his tops and reels and whirligigs fully as many times as Robby did the stockings and mittens; and Mrs. Brown had felt as proud of the hoods and dresses she had made as if they were the only ones that were ever made with human hands.

They were really impatient for the hour to arrive when the children should come to see and enjoy their presents. They had bought many things to add to the precious gifts made with their own hands. Mrs. Brown had visited Baker's Alley again and again, and she had learned that the new Christmas stockings were in danger of soon vanishing if new shoes were not provided. Six pairs of shoes were therefore added to the list of articles to be bought, and complete suits of under-clothing, warm flannels and all things necessary to make six children thoroughly comfortable for winter found their way also to the corner where the treasures were laid up.

CHAPTER VIII.

WHEN the morning of December 31 came, it was as fine a winter day as ever was seen. Mr. and Mrs. Brown were awake early, and he said:

"I think, wife, we will give the children a little sleigh-ride before we bring them to the house to-night. What do you say to that?"

"I like it. It would be delightful for them to have a ride, as I dare say some, or perhaps all of them, would be in a sleigh for the first time."

"I thought of that," said Mr. Brown, "and, as the sleighing is excellent, I am sure we can make them have a splendid time. I will get one of the best barges, and have every thing in the finest style, and we will see what those poor little creatures, who have known nothing but the hardship of winter up to this time, will think of its pleasures."

"Won't a barge be too large for our little company? It seems to me that they will be almost lost, with only eight of them in one of those great barges."

"I will get one of the smaller barges, and as, of course, you and I are to make part of the party, I don't think ten of us will feel lost in it."

"Very well; we can fill up the vacant spaces with warm robes, and the children will perhaps enjoy it the better if they have room to move round a little. But don't you think it would be better to have the ride after the supper and the presents, rather than before? It seems to me . that it would."

"Why? "

"Because they would be better prepared to enjoy the ride after they have on their new, warm garments, and after they have been fed well, than they can be if they go half clad and hungry.'"

"Do you suppose that those children really go hungry, wife?"

"I do not suppose; I know that they do. I have been in some of those houses this week, and found children crying for bread.'"

"'Tis too bad, too bad," said Mr. Brown.

"Let us see if we cannot give them a full taste of physical happiness, for once. I will have a nice warm, hearty supper ready for them, and they shall eat their fill, and then we will try them into the new flannels."

"Are you going to put the new clothing onto them here?"

"Yes, certainly. I am going to have every one of them in the bathtub, with plenty of hot water and soap, and, when they are thoroughly clean, I will dress them in the new garments. Don"t you think that it will be a good sensation to them to be really clean, through and through ? "

"I do; but, if this is going to be done, it must be done before they have their supper, and not afterward."

"Why?"

" Because it would be really dangerous to put them into a bath after they have eaten as heartily as I know they will eat. And, again, another danger will be in putting these children into warm water, and thoroughly opening the pores of the skin, and then taking them out for a long ride in the cold afterward. This danger will, of course, be less if the bath is given an hour or two before the ride, rather than immediately before it."

"In short," said Mrs. Brown, laughing, ""I suppose you think that my making these children clean, may be the death of 'em."

"I don't 'know that it will be that. But you, yourself, will see that there is great danger of your making them sick; and I am sure the poor little things have enough to suffer now, without our adding to their misery."

"Yes; there you are quite right. We will not undertake to make these children happy, and by this very attempt make them miserable. So the arrangement shall be: bath, first thing on arrival; new clothing and comforts, next; and these to be followed with slipper, and a sleigh-ride. I think we shall, all enjoy this plan better, as it gives us the children in much sweeter condition all of the time they are with us in the house."

"Very good," said Mr. Brown; "and now that we have settled all the details, let us see how well we can carry them out, and how happy we can make the children and our- selves."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The evening came, and the guests came with it,Robby and Nellie an hour before the children from Baker's Alley, as Mr. and Mrs. Brown had. arranged, and no suspicion of the pleasure in store for them had entered their minds. They were very happy playing a new game which had been provided for their amusement, during the time that Mrs. Brown was getting the children washed and dressed, and they knew nothing of their being in the house until Mr. and Mrs. Brown came and invited them into the dining-room; and there was the little merry group, all as clean and bright as possible, waiting to receive them.

"Well! well!" said Robby, "here is a New Year's party in real good earnest, and a great many other new things to keep it company. Every thing new about these children except their hands and faces, and they are so clean that they seem like new ones."

The next hour was an intensely happy one to all parties.

Robby and Nellie could not enough admire the clothing that Mrs. Brown had made; and the toys of Mr. Brown's workmanship pleased them all immensely. The supper was served, and never was a supper better complimented by eager appetites.

It was really a delight to Mr. and Mrs. Brown to see the happy children, and to feel that they had been able to bring so much joy to their hearts.

The children had learned by the experience of the Christmas party, and they behaved much more politely than they had done on their first party night.

Nellie, noticing this, said to Mrs. Brown:

"I think you know how to manage these children better than I did. They are not only a great deal prettier, but they are a great deal better behaved. than they were at our house."

"I am very happy to see them so," Mrs. Brown replied; " and all the happiness of our own hearts and of these children, we owe to you. If you had not had them in training at the Christmas party, they would not have behaved as well at this."'

"I don't know about that," said Nellie. "It seems to me that you would have managed them if they had never seen a party before, and I know they arc behaving a great deal better on account of the pretty new clothes which you have given them, and that, you know, I never could have done."

"If it had. not been for the example you and Robby set for us, we should never have found these children, and never have known how best to provide for them if we could have found thorny so that all their present happiness and well-being is owing to you."

While they were speaking, the merry jingle of sleigh bells was heard, and, when the sound ceased at the door, Mr. Brown sprang up, and said:

"Who wants a sleigh-ride?'" And the children cried:

"I," "and I," "and I," "and I," till all the merry voices had joined the chorus.

Then Mrs. Brown brought out the new shawls and hoods that she had provided for the girls, and the caps and furs Mr. Brown had bought for the boys; and the shout of joy that welcomed them was not to be forgotten by those who heard it. Of course the Christmas mittens made a part of the outfit. Never were happier children than those who dropped down among the warm robes of the barge to take their first sleigh-ride.

Mr. Brown and Robby sat at the head of the barge, and Mrs. Brown and Nellie at the foot, to keep the mischievous six in order. But the task was more than they were equal to, for such a fund of frolicsomeness was never equalled in six pairs of hands and feet before.

Peter Prink seized little Tommy Gould and tossed him far out into a snow-bank, and, of course, this involved the stopping of the barge and Mr. Brown's getting out into the snow to pick up the little white bundle, that was found to be entirely unharmed, and as merry about it as a kitten might be that had been tossed into a bed of down.

But this kind of rough play could not be allowed, lest another experiment of that kind might not prove as harmless in its results; and Mr. Brown therefore compelled Peter to sit beside him, and he held one of his hands close in his all the remainder of the ride.

Of course a boy with only one hand at liberty was quite disabled, and yet he contrived to pull Mary Grundy's hair, which, he said, he mistook for his handkerchief, when he was reproved for the act.

This made them all laugh, as Mary's hair was a dull flaxen, and really quite the color of the dirty handkerchief which Peter afterward pulled from his pocket. Not that the handkerchief had been dirty an hour before, when it had been given him among his presents; but in the hour it had served various purposes, such as wiping his shoes, rubbing the extra oil off his hair, with which he had anointed his head in Mrs. Brown's bath-room, and, finally, as the receptacle of some of the preserve that he had particularly liked at the supper and had thought he would like to carry home to lunch on the next day. Little Susie Monroe fell asleep and dropped off the seat into the bottom of the barge, and when Mrs. Brown gathered her into her motherly arms, she said:

" Oh, how nice; I never was hugged before."

This simple expression of contentment from the lips of the little neglected child brought the tears to Mrs. Brown's eyes, and she felt how very sad it was to have a little child living on through the troubles and dangers of childhood, without the compensations of mother-love and tenderness which soften the hard path to nearly all the little ones born into the world. After an hour of the merriest of all merry rides out in the open country, where the sleighing was at its best, the barge came again into the city streets, and drove to the head of Baker's Alley to discharge its freight, much to the amazement of all the people in the alley, who had never dreamed that such a gay cavalcade could come to their quarter of the city.

And so the happy New Year's party was ended as a present pleasure, and left as a beautiful memory in the hearts of all who had enjoyed it.