Copyright 2017 by Deidre Johnson . Please do not reproduce without permission

Like many of her counterparts, series author Catharine (sometimes spelled Catherine) Lydia Hilliard Burnham came from an educated, book-oriented, and religious family. Her father, Francis Hilliard (1806-1878), was a lawyer and jurist who wrote several then-popular legal works including The American Law of Real Property (1838), which reached a fourth edition by 1869, and The Law of Mortgages (1852) which went into a third edition a dozen years after its first publication. [1] Her paternal grandfather, William Hilliard (1778-1836), was a bookseller and publisher, first in 1812 as a partner in Hilliard and Cummings, printing and publishing textbooks for Harvard students, then expanding his business (and, at one point "help[ing Thomas] Jefferson build the library of the University of Virginia"). In 1827, his firm was renamed Hilliard, Gray, & Co., and subsequently, under the leadership of Catharine’s uncle Charles Coffin Little (1799-1869), became Little, Brown & Co. [2] On the religious front, her paternal great-grandfather, Timothy Hilliard (1746-90) was a clergyman; her father, a member of the Episcopal church; both of her brothers became Episcopal priests. All these male relatives were also Harvard graduates. [3]

On her mother’s side, her great-grandfather, Jason Haven (1733-1803), was a minister; her grandfather, Samuel Haven (1771-1847), a judge and register of probate; her uncle, Samuel Foster Haven (1806-81), Librarian of the American Antiquarian Society. As on her father’s side, they were also all educated at Harvard. [4] Her maternal grandmother, Elizabeth (Betsey) Foster (1770-1851), was apparently musically inclined; one relative mentions visiting the family in Boston in 1787 when she played "the Piano Forte with ... delicacy and skill" with "the French Consul and several [others] . . . attending to her music with much delight while her brother accompanied her with the violin." Her mother, Catharine Dexter Haven (1802-1888), enjoyed reading and was "lifelong" friends with Oliver Wendell Holmes’s sister Mary as well as maintaining a regular correspondence with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s wife Sophia [5]

Catharine, born May 17, 1836, was the third of five children -- Francis William (1832-1910), Elizabeth Craigie (1833-79), Samuel Haven (1838-1918), and Sarah McKean (1840-97) . [6] The 1850 census records the entire family together in Roxbury, along with Catharine’s maternal grandmother (Elizabeth Haven) and her aunt (Elizabeth Hilliard). Also in the household were two Irish servants and a nurse. The 1850 census gives her father Francis’s occupation as "lawyer"; by 1855, he had become a "police judge." [7]

In the 1850s, Catharine’s brother Francis William Hilliard spent time in Scuppernong, North Carolina, as a tutor to a Harvard classmate’s siblings. After study at a seminary in New York, he settled for a time in Edenton, North Carolina, serving in his future father-in-law’s church (St. Paul’s). In 1857, he married Maria Nash Johnston and remained at various parishes in North Carolina during and after the Civil War. (His entry in Annals of the Harvard Class of 1852 remarks that because of his time as a tutor on a Southern plantation "his sympathies were . . . always with the Southern cause.") [8]

On April 27, 1859, Catharine married Frederick Gordon Burnham (June 29, 1831 - August 7, 1918). Like Catharine’s father, Frederick was also a Harvard graduate and attorney; at the time of the marriage, he was practicing in New York in a partnership with John Van Buren. [9] He was also a founding member of the Church of the Covenant, and one of the three men selected as elders in its first years. [10] The church membership is noteworthy not just as a sign of character but also because the pastor was George L. Prentiss, husband of series book author Elizabeth Prentiss, who pseudonymously published her three-volume Little Suzy series (1853-56) with Anson D. F. Randolph's firm only a few years before Catharine began writing for children.

In 1862, Catherine published her first children’s book anonymously. One review described Ernest: A True Story, issued by Prentiss's publisher Anson D. F. Randolph, as "a memorial of a bright little boy, twelve years of age, who, full of life and promise, was smitten with disease, and in a few days was laid in the grave. Three months before his death he gave his heart to Christ," adding that the work "has been prepared to show children how happy and blessed a thing it is to be a child-Christian." [11] Another review cryptically remarks, "We assure our readers, from a personal knowledge of many of the facts stated, that it is a true story. The persons and scenes described are familiar to us; and the scene referred to on p. 131 will never fade from our memory." [12] Among those who praised the work was Elizabeth Prentiss, who wrote to author Anna Warner (sister of yet another series author, Susan Warner), saying "If you come across a little book called ‘Ernest,’ published by Randolph, do read it. It is one of the few real books and ought to do good." [13]

Three years later, Randolph published a second title by Catherine, again anonymously -- Don’t Wait; or The Story of Maggie. It received less notice than Ernest, though the reviewer in Hours at Home, after referencing Ernest as "one of the best and most charming books for the young that we remember to have read of late," called Don't Wait "a companion volume . . . which well illustrates the evil of . . . procrastination in everyday life." [14]

During the period between Catharine's books, Frederick left his New York law practice for health reasons and the couple moved to Morristown, New Jersey, where Frederick's family had resided since 1840. He returned to practicing law after a time and in 1868 was admitted to the New Jersey bar. [15]

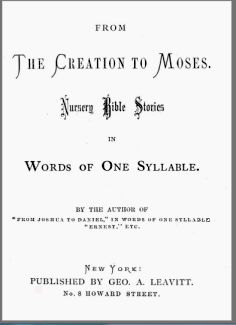

The following year, Catharine published two additional books, this time with the firm of George A. Leavitt. Leavitt issued the volumes as the last half of a four-book publisher’s series featuring (as its title proclaimed) Nursery Bible Books in Words of One Syllable. The first two Nursery Bible Books were the work of another author of girls’ series, Katherine Kent Child Walker (Mrs. Edward Ashley Walker). Walker’s contributions, a simplified version of Pilgrim’s Progress and a life of Christ titled From the Crib to the Cross (both 1869), were followed by Burnham’s retellings of Old Testament Bible stories in From the Creation to Moses and From Joshua to David (both 1869).

Although the series’ title implies very simple language, the prefaces explained that "the language of the Bible has been adhered to as closely as possible," resulting in complex sentence structures and somewhat archaic language. The following example, from "Jacob on His Way Home," the tenth chapter of From the Creation to Moses, offers an example of the style:

Jacob had now been with Laban twenty years, but at the end of that time, God spake to him in a dream, and said, ‘I am the God of Bethel, where thou didst set up the stones for a sign, and where thou didst vow to serve me; now rise, get thee out from this land, and go back to thine own home.’

Then Jacob sent for Rachel and Leah to the field where he was with his flock, and said to them; ‘I see that your father’s face is not as kind to me as it was; but the God of my father hath been with me. Ye know that with all my might I have done my work for your father; he hath not done right to me; but God would not let him hurt me, and hath blest me, and made me rich.’

The series initially received little attention in periodicals, and the reviews seen deal only with Walker's two volumes (which earned mixed responses). [16] In 1886, Catharine's former publisher, A. D. F. Randolph, issued a revised edition of the series, which attracted slightly more notice, albeit primarily in religious publications. The New York Evangelist lumped the entire series into one review, which reads, in its entirety, "These four volumes have been prepared in the monosyllable style for children. Without endorsing the doctrine of one-syllabled words for children, we endorse these books as very engaging and excellent." [17] The Christian Union had a more favorable response when reviewing the three titles retelling Bible stories (Walker's From the Crib and Burnham's two volumes). The reviewer felt they would be "eagerly welcomed by the children" since "Bible stories never fail to secure absorbed listeners; and when told in simple monosyllables, as here, with the Scripture language retained as far as possible, they have a double interest." [18]

Circumstances suggest that Catharine and Frederick cared deeply about children but were unable to have their own. Perhaps adding to their desire for a family was their awareness of their siblings’ growing households. By 1870, Catharine’s brother Francis had six children (a seventh had died in infancy), and Frederick’s sister Julia Burnham Sherman (1828-1915), three (a fourth had died in childhood) plus a stepson. [19] The 1870 census shows that two of Catherine’s nieces from North Carolina -- 12-year-old Maggy and 14-year-old Catherine -- were staying at her home that year. It also indicates that Frederick continued to prosper: the household contained two servants, and Frederick’s real estate was valued at $10,000, while his personal estate was estimated at another $5,000. [20]

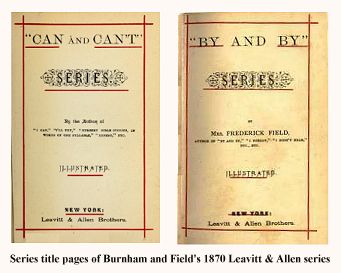

The presence of her nieces may have influenced Catharine Burnham's next books, the three-volume Can and Can’t series, published by Leavitt & Allen Brothers (the next iteration of her previous publisher, George A. Leavitt) in 1870. The series dealt with a family, and each volume focused on a different sibling. The protagonist of volume two, I’ll Try; or, Sensible Daisy, is actually named Margaret, as was one of the resident nieces; in the course of the story, Daisy marries and moves to a plantation in the South. Passages in the third book, I Can’t; or, Nelly and Lucy, also allude to Daisy spending time in the South, though the book is set in the North and Daisy has returned to that region.

In design and title concept, the series resembled another three-volume Leavitt & Allen series from 1870, By and By, written by Mrs. Frederick Field. Indeed, one review, in The Ladies' Repository, even covered both series in one brief, somewhat generic (albeit favorable) review, calling them "very beautiful and very excellent books for children . . . [which] illustrate very happily some of the faults and some of the excellencies of the principles and conduct of child-life," concluding they were "safe books for the family and for Sabbath-schools." Only a few reviewers singled out Burnham's books for particular notice, but those that did were generally favorable. The Sunday-School Times felt the stories were "freshly told" (and also appreciated the "lessons" as "always needed"). According to the reviewer, I Can "shows how the confident enthusiasm and even the reckless daring of an adventurous boy-spirit may be so moulded by grace as to become the basis of a Christian character in after life," while I'll Try offered "a good lesson on the power of a humble, quiet persistency in duty"; only the third volume was less effective in "teach[ing] its lesson." The Christian Union found "the books . . . very pretty in their external and internal appearance and . . . the stories which they contain well told and entertaining." [21]

About 1873, the Burnhams' family situation changed when they adopted a child, Anna Dyke Washburn, subsequently Anna Washburn Burnham. [22] Anna may have been enough to occupy Catharine’s attention fully, for the Can and Can’t volumes were her last children’s books and her last identified publications until the next century. The 1880 census shows the family -- Frederick, Catharine, Anna, and four others (the latter all identified as servants) -- in Morristown, New Jersey. Frederick’s occupation was still "lawyer." [23]

In 1886, the Burnhams further demonstrated their affection for children and dedication to religious principles by donating 580 acres of land and buildings in Columbia County, New York, worth between $150,000-$200,000 (over $5 million in 2016 dollars) to found The Burnham Industrial Farm (now Berkshire Farm Center). The institution was designed to help truants, boys whose parents felt they were unmanageable, and lads who might otherwise have been sent to (or were already in) reformatories by providing them with a more healthful and instructional environment than their current situation. At the Farm, the boys would receive "an elementary English education, and . . . industrial and manual training as will fit them to support themselves . . . in [agrarian pursuits and] a variety of trades." [24] An additional motivation for the Burnhams was the lack of Protestant facilities for such youths; one appeal for funds after the Farm's establishment explained that the current overcrowding of reformatories meant Protestant children were being sent to Catholic institutions for housing and consequently being educated in another faith. [25] By 1887, the Farm already housed 26 boys, seven "committed by magistrates, and nineteen entrusted by parents or guardians." [26] Four years later, the number had increased to 65. [27]

Although Catharine is not mentioned in news accounts of the Farm (which, instead, frequently highlight the dedication of its Resident Director from 1890-93, W. M. F. Round), one internal history credits Catharine "with suggesting the initial idea for the Farm," adding that "[t]he idea that the Farm represented a family, rather than an institution, was a major factor in its success and its powerful influence on the boys’ lives." It states that Mrs. Burnham "got to know the boys well and often corresponded with them after they had left the farm." [28]

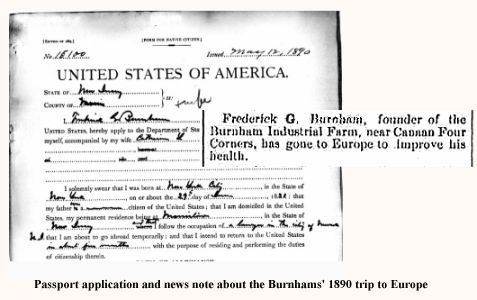

Several changes in Catharine's life occurred during the years after the foundation of the Farm and the turn of the century. She may have been doing some writing during this period, for an 1895 work on Morristown writers lists her both as a poet (without identifying any publications that printed her poems) and an author, stating that "In addition to [her children's books], Mrs. Burnham has, for many years been an occasional contributor to the Churchman, Christian Union and other important papers." [29] (None of these articles have been found.) Her mother died in 1888, having spent her later years with the Burnhams. [30] Frederick appears to have had intermittent health problems, and in 1890, the three Burnhams traveled to Europe on his account. [31] The other major change occurred in October 1897, when the Burnhams' daughter Anna married Samuel Carter, Jr., the son of Rev. Samuel Carter (who performed the ceremony at the South Street Presbyterian Church in Morristown). [32]

During these years, Frederick (and, presumably, Catharine) continued engaging in charitable works and public service as well as social activities. In 1899, Frederick was serving on the New Jersey State Board of Children's Guardians and on the Advisory Council for the New Jersey Legal Aid Association [33] The Burnhams have not been located in the 1900 census, and it is possible they were traveling at the time: an assortment of local news notes in regional papers mention the Burnhams' trips, sometimes to a cabin in the Adirondacks and, on at least one occasion, to California. [34] During the 1890s or 1900s (and probably earlier) Catharine was also a member of several organizations, including the Women’s Committee of Home Missions and the New Jersey Society of Colonial Dames. [35]

One of Catharine’s last identified publications was a short article from 1901 in The Evangelist, again evincing her interest in Burnham Industrial Farm. Titled "A Story of Berkshire Farm" (the farm's new name), it told of a hypothetical teen, recently abandoned by his mother and with his father in jail for burglary, wondering what to do with himself. Knowing that "he had not been a good son and had run away and stolen rides on the freight trains numberless times" and worried that "his strange faculty . . . for opening locks" would lead to his father’s fate, he happened across a notice about the farm. They took him in, trained him, and despite setbacks, helped him to find an occupation he enjoyed. [36]

The 1910 census shows the Burnhams’ continued prosperity; the household included a gardener and cook and their 2-yr-old son. Frederick owned their home, with no mortgage. The following year the Burnhams donated a 28 acres of land known as Burnham's Woods to be used for a public park in Morristown. [37]

Catharine's last known publication dates from 1913. Issued by the Presbyterian Board of Publication, Daily Treasures, "arranged by Catharine L Burnham," is described as a "little volume as an aid and incentive in the observance of family worship" with readings on Christ’s life. [38] Four years later, on March 10, 1917, after "a brief illness," she died in Morristown, New Jersey. [39] Frederick survived her by a year and both are buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Morristown. [40]

1. Biographical information about the Hilliards can be found in Hilliard-Pratt Family Papers 1834-1909 (finding aid) and "Francis Hilliard (1806-78), c. 1835,", both American Antiquarian Society, as well as "The Hilliard Line," Encyclopedia of Massachusetts (American Historical Society, 1916): 230-32. A portrait of Francis Hilliard circa 1835 is online at Portraits at the American Antiquarian Society . Additional information about the Hilliard family is from the John McCarten, Boye, Newell, and Powers family trees on Ancestry.com.

2. John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United States, vol. 1 (Bowker, 1972) : 442-43.

3. "Hilliard-Pratt Family"; "Francis Hilliard" (obituary), New York Tribune, Oct. 14, 1878: 2; "Francis Hilliard" (obituary), Boston Journal, Oct. 11, 1878.

4. Theodore F. Rodenbough, Autumn Leaves from Family Trees 1066-1891 (Privately printed, 1892): 59, 63-65;

5. Frederick Haven Pratt, "The Craigies," Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society 27 (1942): 52, 67.

6. Rodenbough, 63-64.

7. 1850 U. S. Federal Census, Roxbury, Norfolk, MA, Roll: M432_330; Page: 83A, Ancestry.com; 1855 Massachusetts State Census, Roxbury, Norfolk, Ancestry.com.

8. Grace Williamson Edes, Annals of the Harvard Class of 1852 (Privately printed, 1922): 101-02.

9. "Mr. Frederick G. Burnham" (obituary), New Jersey Law Journal 41 (Sept. 1918): 288; "Burnham, Frederick Gordon," Universities and Their Sons ( R. Herndon, 1900 ): 59-60. A newspaper article, "Developer of the East Side," discusses another aspect of Burnham's business career generally missing from biographies -- his activities as a land developer (Asbury Park [NJ] Press, April 18, 1971: 21.

10. "Eleven Years in the Church of the Covenant," New York Evangelist, Jan. 15, 1874: 2; George L. Prentiss, "The Mercer Street Presbyterian Church from 1835 to 1858," New York Evangelist Dec. 26, 1895: 13.

11. "Book Notices," Methodist, Aug. 20, 1864: 258.

12. "Literary and Critical Notices of Books," American Presbyterian & Theological Review, New Series, 1 (Jan. 1863): 172.

13. The Life and Letters of Elizabeth Prentiss (Anson D. F. Randolph, 1882): 211.

14. "Books of the Month," Hours at Home 5 (May 1867): 94.

15. "Burnham," New Jersey Law Journal.

16. An 1869 review of Walker's volumes states of the concept of simplifying the language "We think this is a great mistake," believing that "alter[ing] the scriptural account . . . materially deteriorates the value of the whole picture presented"; the reviewer also felt that Pilgrim's Progress was essentially unsuitable for "children who are so young as to require it to be set forth in words of one syllable" (Review of From the Crib to the Cross and Pilgrim's Progress, The Friend, Nov. 6, 1869: 11).

17. "Our Book Table," New York Evangelist, Dec. 16, 1886: 50.

18. Untitled review, Christian Union, Feb. 24, 1887: 8.

19. Edes 101-02; "Charles Pomeroy Sherman," Sherman Genealogy (Brooks & Idler, 1922): 39-40, 52-55.

20. 1870 U. S. Federal Census, Morristown, Morris, New Jersey; Roll: M593_877; Page: 288B, Ancestry.com.

21.

"Contemporary Literature," The Ladies' Repository 31 (May 1871):396' "Books" The Sunday-School Times, Oct. 22, 1870: 685 ; "Brief Notices," The Christian Union, Jan. 4, 1871: 7. The Christian Union review includes more specific plot information for I Can; or, Charlie's Motto: "an American boy . . . gets into no end of scrapes during his school and college days, and finally becomes a missionary."

22. Anna's name change by reason of adoption appears in Acts and Resolves Passed by the Court of Massachusetts in the year 1874; a record of her birth, along with family trees and death certificates for her biological parents, can be found on Ancestry.com. Her parents' names are recorded as Elisha Washburn and Rebecca (maiden name Dike or Dyke); Rebecca died in November 1869; Elisha, in April 1870. The 1870 census suggests she was living with her half-sister, Lizzie J. Washburn, age 17, and her 3-year-old brother Elford (or Alford), in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Her whereabouts after the 1870 census and before her 1873 adoption are not known. (1870 U. S. Federal Census, North Bridgewater, Plymouth, Massachusetts; Roll: M593_639; Page: 564B; Ancestry.com).

23. 1880 U. S. Federal Census, Morristown, Morris, New Jersey; Roll: 793; Page: 208A; Ancestry.com.

24. "Items," The Friend, Jan. 29, 1887: 26. See also "A Noble Charity," The New York Evangelist, Feb. 10, 1887: 4

25. "A Noble Charity."

26. Wm. R. Stewart, "The Burnham Industrial Farm, Canaan, Columbia County, N. Y.," Annual Report of the [New York] State Board of Charities for the Year 1887 (Troy Press, 1888): 331.

27. W. M. F. Rounds, "The Burnham Industrial Farm," Christian Union, Sept. 12, 1891: 500.

28. "Explore the History of Berkshire Farm," New York Correction History Society; the website notes text and images are from "Berkshire Farm's Archives brochure."

W. M. F. Round, who served as director soon after the Farm's establishment, wasoften mentioned in articles publicizing the Institute's mission and activities. See, for example, George L. Clark, "How Burnham Farm is Saving the Boys," Christian Union, July 24, 1890: 4 and "The Burnham Industrial Farm," New York Times, March 22, 1891: 9. Round also wrote articles about the Farm and appeals for funds, even after retiring as Director. For an example of the latter, see his letter, titled "Burnham Farm,"Outlook Dec. 16, 1893: 1144. Ironically, he resigned from office in 1893 because of concerns about his management ("The Burnham Farm," Hudson Daily Evening Register, Aug. 7, 1893: msg. pg.).

The institution is currently known as Berkshire Farm Center & Services for Youth and, according to its website, "is one of New York State’s leading nonprofit child welfare agencies, serving 8,500 children and their family members across New York State in 2014 alone."

29. Julia Keese Colles, Authors and Writers Associated with Morristown, 2 nd ed. (Vogt Bros, 1895): 120, 197-99. A related volume, New Jersey Scrapbook of Women Writers, compiled by Margaret Tufts Yardley (Advertiser Printing House, 1893), also carries two poems by Burnham, "Beethoven's Fifth Symphony" and "The Pattern Seen on the Mount"; part of the former is reprinted in Colles.

There are no biographical sketches in Scrapbook, and its title page states it was "published by The Board of Lady Managers for New Jersey to Represent the Many Writers Who Are Not Bookmakers at the World's Columbian Exposition," an odd statement since Burnham's books were included in the exhibit. (A digital version of List of Books Sent by Home and Foreign Committees to the Library of the Woman's Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. is online at A Celebration of Women Writers.)

30. "Hilliard-Pratt Family Papers ."

31. Frederick L. [sic] Burnham, National Archives and Records Administration Series: Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Roll 349 - 09 May 1890-16 May 1890, and Ann Washburn Burnham, National Archives and Records Administration Series: Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Roll 349 - 09 May 1890-16 May 1890, both Ancestry.com. Untitled item, Kingston Weekly Freeman and Journal, June 19, 1890: 3 (source of news image); see also "Burnham Industrial Park," Chatham Courier, msg. cite, which noted that the Farm sent a delegate to the ship to deliver a wildflower bouquet picked by the boys and convey their good wishes.

32. "Married," New York Daily Tribune, Oct. 22, 1897: 7.

33. "Taxation," New York Tribune, April 26, 1899: 8; "A Legal Aid Association Formed," New York Tribune, Jan. 15, 1899: 39.

34. "Morristown," New York Tribune, Feb. 23, 1895: 12; "Morristown," New York Herald, April 28, 1895: msg. pg. The first announced the start of the trip; the second, the return. The following year, a July news item stated that Frederick was "resting for the summer months at his camp at Old Forge, in the Adirondacks" ("Morristown," New York Tribune, July 19, 1896: 18.)

35. "Women's Executive Committee of Home Missions," The Evangelist, March 19, 1896: 22; "Colonial Dames of New Jersey Will Assemble at Annual Session in Trenton," Trenton Times, May 4, 1903: 1.

36. Catherine [sic] L. Burnham, "A Story of Berkshire Farm," The Evangelist, April 18, 1901: 21.

37. 1910 U. S. Federal Census, Morristown Ward 2, Morris, New Jersey; Roll: T624_902; Page: 16A, Ancestry.com; "New Parks," Park and Cemetery 21 (May 1911): 539.

38. "Sermons, Addresses, Studies of the Gospels," The Continent, Aug. 7, 1913: 1101

39. "Deaths" (obituary), New York Evening Post, March 12, 1917, msg. pg.; Rich H., "Catharine Lydia Hilliard Burnham," Find a Grave

40. Rich H., and D. S. Johnson, "Frederick Gordon Burnham," Find a Grave.