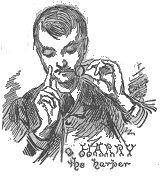

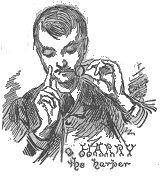

The Three Vassar Girls is another example of a travelogue series (similar to the Hales' Family Flight). The first few chapters of the series' second volume show the emphasis on illustrations, which were taken from a variety of sources. The three sketches of men in chapter one were all the work of Elizabeth Champney's husband, J. Wells Champney. His signature, "Champ," is barely visible over the shoulder of Mr. Atchinson and next to Harry's the Barber's left wrist. More of Champ's work appears in chapter two, depicting major characters in the story.

The Three Vassar Girls is another example of a travelogue series (similar to the Hales' Family Flight). The first few chapters of the series' second volume show the emphasis on illustrations, which were taken from a variety of sources. The three sketches of men in chapter one were all the work of Elizabeth Champney's husband, J. Wells Champney. His signature, "Champ," is barely visible over the shoulder of Mr. Atchinson and next to Harry's the Barber's left wrist. More of Champ's work appears in chapter two, depicting major characters in the story.

THREE VASSAR GIRLS

IN ENGLAND.

A HOLIDAY EXCURSION OF THREE COLLEGE GIRLS

THROUGH THE MOTHER COUNTRY

BY

ELIZABETH W. CHAMPNEY

ILLUSTRATED BY "CHAMP"

AND OTHER DISTINGUISHED ARTISTS

BOSTON:

DANA ESTES AND COMPANY

[1884]

CHAPTER 1.

ND in spite of all this I do not like the English!"

" Barbara Atchison ! "

"You surely do not mean that you do not like your cousins."

" No, I except them. They seem to me almost like Americans' but English people typically and collectively impress me as the most antipathetic,--the most disagreeable on the face of the earth.

"And yet," remarked Cecilia Boylston, the eldest of the three, a dignified girl with a face as pure and clear as her pebble eye" glasses, "you were in raptures a moment ago over this fascinating little country-house, with the ivy clinging to the stepped gables, making such a rich contrast to the red brick, over this cozy alcoved window, with that wonderful view, over all the quaint ways of the household, and the Chippendale furniture. What is it that strikes the false note ? "

"Nothing, just here. It is all perfect. Nobody could find fault with Cosietoft or with my good relatives. When I think of how Cousin Acherly Atchison left his business at Manchester and

departed forthwith to America to hunt up his unknown cousins, just because a legacy had been left in which we had a share, his conduct seems to me worthy of one of the knights at Arthur's Table Round. Why, most people would have been content with inserting a personal in the Herald, and trusting to our never seeing it."

"Then," added Maud Van Vechten,--a business-like young woman already sharpening her pencils preparatory to sketching the towers visible in the distance, -- " then it was perhaps quite natural that he should insist on taking you back to England with him to visit in this delightful family, but that he should invite Saint and me as well, because we were friends of yours, and happened to be passing through Derbyshire on our way to London, -- why, such hospitality wins my heart, not only for Mr. and Mrs. Atchison, but warms it to all their country-people."

"If this were all," replied Barbara, "or if all were like this; but Aunt Atchison is determined that we shall see some society; and presently we shall have to meet the dreadful bores that figure in Trollope's novels, and whom even Dickens and Thackeray could not make entertaining. If we could wander at our own sweet will through this lovely country, with only books to interpret it for us, but no, we must meet stupid people and opinionated people, talking bores and dignified bores, and for uncle and aunt's sake I must try to propitiate all."

" I sympathize with you, Barb," Maud remarked. " The less we see of people the better. If they are disagreeable it is always difficult to shake, them off, and if one likes them they make us fritter away our time. Imagine having to spend whole days on afternoon teas, calling, and picnics, when one might be sketching Kenilworth or Warwick Castle ! "

"There is to be a grand lawn-party at Chats-worth next week to begin with, which we cannot escape. Cousin Dick is corning up from Oxford to attend it, and even Tom, who scarcely ever leaves his business at the Royal Porcelain works, is to be here. That will be our debut, and after that I fear Aunt Atchison will get up some minor festivities on her own account. I besought her not to do so. I told her we were very simple in our tastes, and would much prefer that she should not make a fuss over us. The two quiet days that we have spent in this rambling old house have been more than delightful. I am afraid they are too good to last. Harry is only a boy of sixteen, and a good-natured and endurable young fellow, but I confess that I dread the coming of my older cousins, though we may congratulate ourselves that they cannot stay long. Then think of the fossils of clergymen and dowagers, and old squires, and narrow-minded women that we will have to meet! Their patronage of America will be even worse than their downright rudeness. I think we have an innate prejudice against the English, and they against us. It is as intense and as irrational as our longing to snap torpedoes on Fourth of July, and perhaps the feeling and the custom date back to a common origin."

"I am glad that you recognize the feeling as prejudice," replied Cecilia, familiarly called Saint. "I who was born under the shadow of Bunker Hill have no such vindictive feeling. If I had lived at the time of the Revolution I have no doubt my blood would have been stirred by the reverberations of the great guns', but this popping of crackers and international squibs of criticism seem to me alike childish."

"What I find particularly galling," continued Barbara," is the fact that the English are so supercilious. They fancy that they understand us perfectly, while they have not the remotest conception of what Americans really are."

" I can pardon the arrogance which comes from misconception," remarked Maud; "what I find absolutely incomprehensible is their lack of taste. Do you remember how those English women in Paris used to dress? They were the laughing-stock of the French. Five shades of purple in one costume, and crimson and magenta married most unlovingly in another gown, while a Paisley scarf with a vermilion centre completed the horror."

" I thought the aesthetic craze had put an end to such atrocities."

"Yes, their artists are teaching them new and better ideas, but Oscar Wilde, and Patience, and Du Maurier's caricatures in Punch show us to what an extreme they are carrying the new fashion. I am more and more convinced that the English as a nation are utterly tasteless."

Saint laughed merrily. "Girls," she exclaimed, "if any one needs to have their impressions corrected, I am sure you do. I foretell that before we have passed three months in England both of you will dote on the English. I believe that all antagonism comes from imperfect knowledge. "What could be kinder than the reception that we have received here ? Mrs. Atchison, too, dresses neither in violent purples nor in dirty greens, but in conventional black. We ought to remember also that we are English ourselves, only a few generations removed, and I for one am ready to believe that all English people are agreeable, could we thoroughly know them."

Barbara shook her head doubtfully. " Cousin Acherly admits that English people have wrong notions about American girls, and he does us the compliment to think that acquaintance with us will enlighten some of his benighted neighbors. I do hope that I shall not disappoint him. No fears about you two, but my evil genius will be sure to lead me into some escapade."

" Never fear, Barb," Maud replied, reassuringly, " you couldn't do anything really shocking,--no matter how hard you tried. It is rather crushing to think that the reputation of America, and Vassar as well, is at stake in our insignificant persons. But I believe that the less we think about it the better. If we go straight ahead without deferring to any one's opinion, simply minding our own concerns, I am sure we cannot scandalize any rightly-disposed person, while if we are continually wondering what Mrs. Grundy will say, we will blunder into no end of faux-pas from sheer self-consciousness. Of one thing I am sincerely thankful, we have no chaperone to be responsible for. I am afraid that when we were in France together we earned the reputation of being rather giddy, simply because my married sister Lilly was the figure-head of the party. We will sail under our own flag this time, and I have no fear that we shall put it to shame."

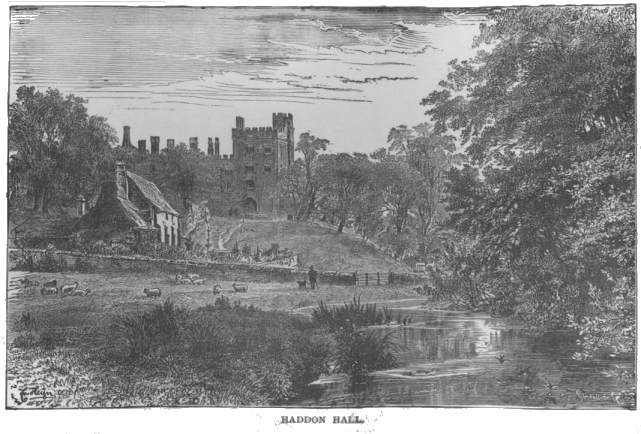

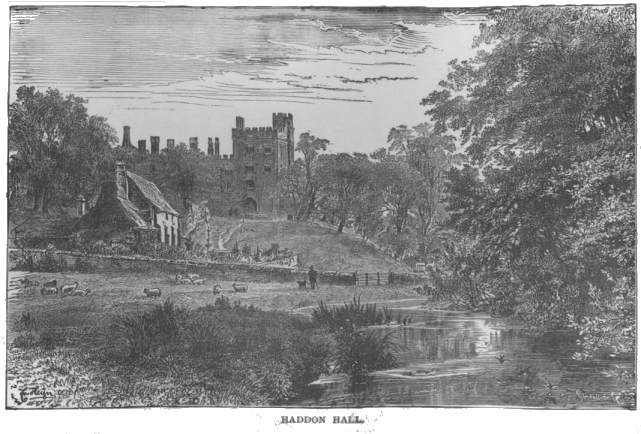

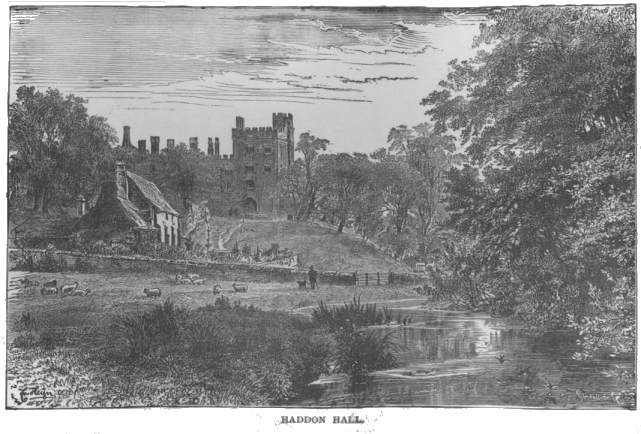

As they spoke Mrs. Atchison rustled gently into the room. "Luncheon is ready, my dears," she said, pleasantly; "and after that is disposed of, I have ordered the wagonette for a short drive over to Haddon Hall. Our bad weather of yesterday has cleared away, and Harry is impatient to do the honors of the neighborhood."

They were joined at luncheon by Harry and by his tutor, Mr. Ives; 'an uninteresting dyspeptic," Maud has systematically labelled him on the occasion of their first interview.

" What is your impression of the view of Haddon Hall which we obtain from the library?" he asked of Saint.

" It is even more English than I had expected," she replied. The rest laughed merrily.

" Did you think it would be like Boston ? " Maud asked.

" I was afraid it would be simply commonplace. So many of the noted places that we saw in Europe might just as well have been in Massachusetts or New York State for any perceptible difference in character. But this is plainly and unmistakably a leaf from the Waverley Novels. It could not be France, or Spain, or America; it is really what it pretends to be, and what is better, it has the appearance of being what it is."

"It is really Haddon Hall," Mrs. Atchison replied; "the old domain of the Avenels, the Vernons, and the Manners'. It is the castle, too, that Sir Walter describes in ' Peveril of the Peak.' This part of Derbyshire is called the Peak, you know."'

" I have brought my set of the Waverley Novels with me," Saint confessed, "and intend to interlay it with photographs of castles, abbeys, and other interesting material which I may find in this tour."

"And I desire to fill my sketch-books before we reach London," said Maud.

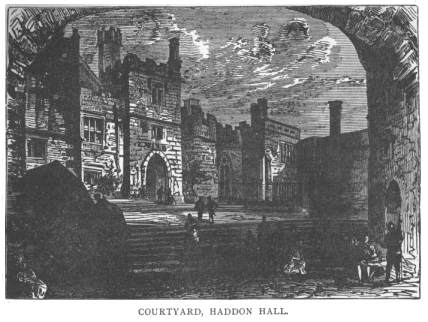

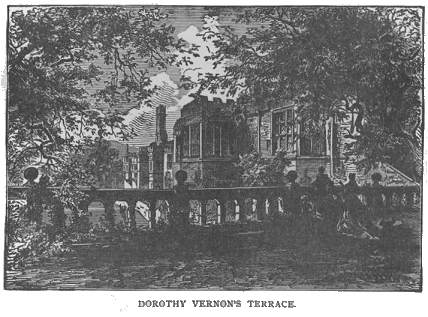

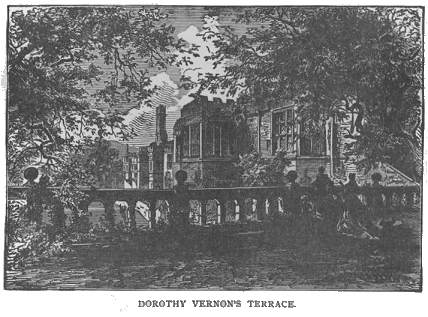

" Dorothy Vernon's Terrace," .said Mrs. Atchison, rising, " would make a very pretty sketch. And so would the courtyard."

They crossed the Wye, and approached the entrance in the main tower. The battlemented turrets rose grandly over the trees, and Maud could not repress her enthusiasm. " What an interesting old feudal fortress! "

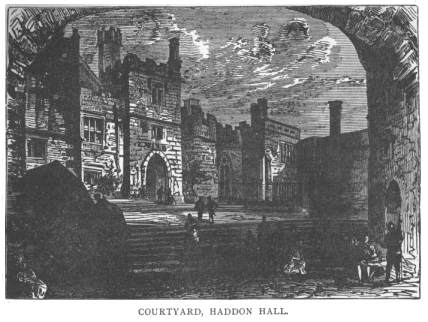

"I beg pardon," replied Mr. Ives; "the Hall hardly deserves to be called old, it only dates back to the fifteenth century, when the feudal period had quite passed away. They entered the great hall, adorned with stags' horns, with a gallery for the minstrels running across the end, and then passed on into the once splendid dining- room, whose carved ceiling still retained vestiges of tarnished gilding. Here they amused themselves by tracing 'the boar's-head, the device of the Vernons', and the peacock, that of the Manners', in the carvings of the fireplace and cornice. Through other interesting apartments hung with arras, they continued their walk into the grand gallery.

" When the family lived here," Harry explained, "they used to give balls in the gallery. It's just your bad luck that you live in this century; you might have had it to say that you had danced on the very floor that Queen Elizabeth tripped it on years ago."

" What is to hinder our dancing now? " asked Barb, " Didn't I hear you practising on the key-bugle last night, Harry?"

" No, that was Mr. Ives, and I don't believe he happens to have it about him, but if a jews-harp will do"--and placing a large one between his teeth he buzzed away with a merry jig, and Barbara, encircling Maud's unwilling waist, whirled her off. No one looked at all shocked, ; while Aunt Atchison beat time good-humoredly with her fan. Just at the height of the merriment a door opened, and a group of other visitors looked in upon them. Barbara had a swift vision of the scornful face of a tall English girl, who turned away after the first glance with contemptuous dignity.

Aunt Atchison and Saint were standing with their backs to the door, and had not seen the newcomers, but Harry dropped his jews-harp with mock terror. " Now isn't this a go!" he exclaimed, "That was Miss Featherstonhaugh and some of her friends, that she has up from Girton to attend the lawn-party at Chatsworth."

Aunt Atchison looked much annoyed. " How extremely vexatious! " she exclaimed, unguardedly.

"What is it, dear auntie; have we done anything very dreadful ? " Barbara asked.

"No, my dear; it was simply amusing, and quite proper; but Miss Featherstonhaugh is one of the persons on whom Mr. Atchison counted on your making a favorable impression. For so young a person, she is considered very learned, having just graduated at Girton College, Cambridge. She is formal in manner, and I fear a trifle opinionated."

" She's a number one prig! " Harry interpolated.

" I see," Barbara mused, in a tone of deep despair. " It is just my evil genius that gives us this unfortunate introduction. I have spoiled everything."

" Why should you care ? " Maud inquired, in a business-like way. "If Miss Featherstonhaugh is a person to be prejudiced by such a trifle why she's not worth minding. I've no doubt the Girton girls waltz and romp when they are alone and unobserved, as we though . we were. I would like to make a study of her face; the corrugator supercilii muscles, and the levator nasi were called into such beautiful action."

" I don't care a pin-head's weight for Miss Featherstonhaugh as Miss Featherstonhaugh," Barbara replied, " but you see Cousin Acherly has made a point of our propitiating her, and after what has happened how can I ever do it."

" Ignore this contretemps," counselled Cecilia, " make her acquaintance, and talk over college matters together. If she's an enthusiastic Girton girl, of course she's interested in the experiment of higher education for woman on our side of the water, and there's a bond of union at the outset."

" She will probably call upon you," remarked Aunt Atchison, " and you will meet her at the lawn-party at Chatsworth. The invitations from the Duchess of Devonshire include all, and to-morrow the boys will come home to attend the festivities, and the county will do its best for you. Do not afflict yourself, dear child, about Miss Featherstonhaugh. I have no doubt that all will end precisely as Miss Cecilia predicts."

They went out upon Dorothy Vernon's terrace, and from it descended into the garden, where the very yews were cut into fantastic boars'-heads and peacocks. "This is where Dorothy Vernon eloped with her lover, John Manners," Aunt Atchison explained. She spoke gayly, and it was perhaps to distract Barbara's mind from the recent unpleasant occurrence that she began the romantic legend of the ancient mansion.

" The King of the Peak, the last of the name of Vernon who owned the castle, had two daughters, Margaret and Dorothy. Margaret was betrothed with her parent's consent to the son of the Earl of Derby; but Dorothy had formed an attachment, for some reason not approved by her father, for young John Manners, son of the Earl of Rutland. On the very night of the marriage of the elder daughter, John Manners, who had been lurking about the place for some days in the disguise of a forester, caused his horses to be brought to the confines of the park, and just when the merriment in the castle was at its height, when the beacons blazed on the turrets, the tables in the great hall groaned with wassail, and the minstrels were playing their gayest wedding march,--Dorothy, stealing out of the banqueting hall, joined her lover at the foot of this terrace."

"It is just the spot for an elopement," remarked Cecilia; "only notice how the trees of the park encroach on the garden. Lover or enemy might approach quite near without detection. I wonder if Tennyson drew from this legend a part of his ' Maud.' The Hall and the Hall garden are here, and the picture of the revelry in the castle --

" All night have the roses heard The flute, violin, bassoon : All night has the casement jessamine stirred To the dancers dancing in tune."

And so, too,

" The lily whispers, ' I wait.' "

"Are you quite sure," queried the correct Mr. Ives, "whether the instruments you mention were used at that remote period? It seems to me that a harp would be more probable."

"Or a jews'-harp?" Maud asked, mischievously.

" I think it an instance of very bad manners," Barbara added, demurely.

"0, come now," pleaded Harry, "don't begin that sort of thing. There's no end to the bad puns that can be made on the name."

"I remember," added Mrs. Atchison, smilingly, "that my nurse used to impress it on my mind that I must not help myself to the last piece of cake in the basket, for that belonged by right to the Duke of Rutland. It was not until I had attained to years of discretion that I comprehended that the expression ' Leave something for manners,' did not really refer to the feudal rights of our seigneur."

At the death of the King of the Peak Dorothy Vernon's husband was the first of his name to own Haddon Hall, and it has remained ever since in the possession of his descendants."

After lingering a while longer in the garden they returned to the interior of the castle, for Cecilia was anxious to identify the nursery with the Gilded Chamber which Scott describes as the play-room of Julia Peveril and little Alice Bridgenorth. There was no trace, however, of the hangings of stamped Spanish leather, representing" tilts between the Saracens of Granada and the Spaniards under Ferdinand and Isabella. Mr. Ives scrutinized the wall carefully for the sliding-panel or concealed door into the priest's chamber, where the Countess of Derby, Charlotte de la Tremouille, was said to have been secreted during her flight from the Presbyterians. " I fear," he said, "that it existed only in Sir Walter's imagination."

"Oh! don't destroy my faith in the Waverley Novels," Cecilia besought. " When we were in Granada we made Irving's ' Tales of the Alhambra ' our guide-book, and we found the localities absolutely correct. I had determined to let Sir Walter Scott introduce me to England, and I can't afford to lose my confidence in his veracity at the outset."

"But Scott does not pretend that Martindale Castle is a literal picture of Haddon Hall," apologized Mrs. Atchison. "" He simply acknowledges that Haddon furnished him his material."

"There is one room, however," replied Cecilia, "which I am sure must be authentic,--the boudoir of the mistress of the mansion, a tapestried chamber with a number of sally-ports. One leading to the family bedroom, another to the 'still-room' and the garden, a third to a little balcony which jutted into the kitchen, from which she could scold the cook, and a fourth to the gallery of the chapel. I have never forgotten the description, for it was so suggestive of the leading employments of a lady of that period."

"There is some authority for that picture," replied Mr. Ives, "for there is a communication between her ladyship's pew in the chapel and the cook's department. She had only to open a scuttle in the wall to ascertain whether the preparation for dinner was keeping pace with the progress of the sermon."

" Dear me," murmured Barbara, " how the spirit's free flight must have been clogged by such telephonic connection with a lower region."

" It needs no telephone from the kitchen to tell me that it is near dinner-time now," remarked Harry, and the party turned reluctantly from the fascinating castle. As they entered the vestibule of Cosietoft, the serving-man presented Mrs. Atchison with several visiting-cards.

" Miss Featherstonhaugh and her friends have called during our absence!" she exclaimed.

" I wonder whether it was before our encounter at the Hall," asked Harry.

" If you please, mum, they only left a few moments ago."

"Then it was their phaeton we caught a glimpse of as we entered the lane," said Barbara; and as the girls mounted the staircase to their own rooms she added, "It's a cut direct. She knew we were at the Hall and hurried over here to make her call while we were away."

Cecilia smiled vaguely. " Miss Featherstonhaugh's brother was more cordial," she remarked, as she passed on to her little bedroom in the tower.

The other girls, who shared the same dainty apartment, turned and looked at each other in wide-eyed surprise. Maud spoke first. "How obtuse in me! It never occurred to me that the name was the same."

" I dare say that it is a very common one," Barbara replied; "there are probably no end of Featherstonhaughs in England. But would it not be a fatality if this should prove to be the same family ? "

" Barbara Atchison, if you wish to be impressive, do take those hairpins out of your mouth. There is not the least likelihood that this young lady with the elevated nose is at all related to him." " I did not notice any resemblance."

" To that good-natured, agreeable Mr. Featherstonhaugh! How absurd."

On to chapter two

Return to main page

Scanned by Deidre Johnson for her 19th-Century Girls' Series website; please do not use on other sites without permission

The Three Vassar Girls is another example of a travelogue series (similar to the Hales' Family Flight). The first few chapters of the series' second volume show the emphasis on illustrations, which were taken from a variety of sources. The three sketches of men in chapter one were all the work of Elizabeth Champney's husband, J. Wells Champney. His signature, "Champ," is barely visible over the shoulder of Mr. Atchinson and next to Harry's the Barber's left wrist. More of Champ's work appears in chapter two, depicting major characters in the story.

The Three Vassar Girls is another example of a travelogue series (similar to the Hales' Family Flight). The first few chapters of the series' second volume show the emphasis on illustrations, which were taken from a variety of sources. The three sketches of men in chapter one were all the work of Elizabeth Champney's husband, J. Wells Champney. His signature, "Champ," is barely visible over the shoulder of Mr. Atchinson and next to Harry's the Barber's left wrist. More of Champ's work appears in chapter two, depicting major characters in the story.