CHAPTER III.

STORY OF THE FOG ON THE MOUNTAINS.

THERE was once a girl named Mary, who lived with her father and mother, in a farm-house at the foot of the mountains. When she was about eight years old, her mother taught her to milk, and she was very much pleased with this attainment.

Her father made her a little milking stool with three legs and a handle, which she used to keep upon the barn yard fence, by the side of her mother's larger milking stool ; and every morning and evening she went out, and while her mother was milking the two other cows, she would milk the one which she called hers. Her cow's name was May-day.

One night May-day did not come home with the other cows; but Mary's mother said that she thought she would be in the lane at the bars the next morning. But on the next morning no May-day was to be seen; and Mary asked her mother to let her set off after breakfast, and go up the mountain and find her. For the pasture. where the cows fed, extended some distance up the sides of one of the mountains. Her mother consented, and Mary put some bread and cheese in a little basket for luncheon, and bade her mother good morning, and went away. She crept through the bars which led to the lane, and then followed the path, until she disappeared from view among the trees and bushes.

After a short time, she came to a brook. The path led across the brook, there was a log across it for Mary to walk on. She stopped upon the middle of the log to look down into the water. The bed of the brook was filled with stones, which were all covered with green moss, and the water, in flowing along, seemed to be meandering among tufts of moss. It was very beautiful.

Mary determined to come some day and get some moss from these stones, and make a moss seat near the house, to sit upon; and then she reflected that she ought not to stop any longer looking at the brook, but that she must go on in search of her cow. So she walked along to the end of the log, and then stepped off, and followed the path which led through the woods, gently ascending.

In about half an hour, Mary came out into an opening; that is, to a place where the trees had been cleared away, and grass had grown up all over the ground. There were several clumps of trees growing here and there, and a good many raspberry bushes, with ripe raspberries, upon them. Mary thought that, after she had found the cow, she would gather some of the raspberries, and eat them with her luncheon. So she went on to the top of a little hill, or swell of land, which was in the middle of the opening, and looked around.

The cow was no where [sic] to be seen. The opening was bounded by woods, in every direction. On one side, these woods extended far back among glens and valleys, and up the sides of the mountains. On the other, Mary could see over the tops of the forest trees, away to her father's house, which was far below her, down the valley. She could distinguish the house and the barn, and the long shed between them; and presently she noticed something moving in the barn yard, and by close attention she made it out to be her father with the cart and oxen going off to the field.

There was, however, a kind of mist slowly creeping up the valley, which soon began to hide this group of buildings from Mary's view. It was one of those mornings in autumn when a fog hangs over the rivers and brooks, and creeps along the valleys, and at length, as the morning advances, it rises and spreads until the whole country is covered; and then it breaks away, and floats off in clouds, and is gradually dissipated by the sun. The fog was rising in this way now, and Mary watched it for a few minutes, as it moved slowly on. First the barn yard fence disappeared; then the barn; then the house, all but the chimneys, then the barn; and finally nothing but a great white cloud could be seen covering the whole. As Mary looked around her, she saw similar fog banks lying in long, waving lines over the courses of the streams, or spreading slowly through the valleys.

She took one more look in every direction, all around the opening, for the cow; and then she concluded that she would eat her luncheon, before she went any farther. There were two reasons for this; she began to feel hungry, — and then she was tired of carrying her basket. So she lightened her basket by eating up the bread and cheese, and then rambled around among the raspberry bushes for some minutes, eating raspberries.

When, at length, Mary came out from among the bushes, she was surprised to find that the whole country all around the little hill, that she was standing upon, was covered with fog. It looked like a sea, or rather like a great lake surrounded by mountains in the distance, and spotted with islands, which were, in fact, the summits of the nearer hills, which rose above the surface of the vapor.

Although Mary could still thus see a great deal of land, yet it looked so strange to her, that she could not recognize any of it. The hills were her old familiar friends, but she did not know them under the disguise of islands and promontories in a lake. She did not know what to do.

She concluded, however, pretty soon, that she would ramble about a little while, looking for the cow, but not far away from the hill, and then, when the fog should clear off, she could see which way to go. So she came down the hill, and began to walk about the opening, and in the edge of the woods; but no cow was to be seen.

At one time, when she had got into the woods a little farther than usual, following a little path which led along a green bank under some tall maples, she observed a gray squirrel, running, or rather gliding, along a log, with his plume of a tail curved gracefully over his back. From the end of the log he passed through the air, with a very graceful leap, to the extremity of a low limb hanging down from a great hemlock tree. The limb bent down with his weight almost to the ground. He ran up the limb to the body of the tree, and then up the tree half way to the top, where he ran out to the extremity of a long branch; and then leaped across, at a great height, into the top of a maple which grew at a little distance. Mary was delighted with the beautiful form and graceful motions of the squirrel, and she followed him along, until at last he ran into a hole in the side of a monstrous tree. It was rather the trunk of a tree,—for it was so old that the top had long since fallen away, and left the trunk alone standing,—old, shaggy, and hollow. His nest was there.

Mary waited a few minutes to see if he would come out; but he did not. Just at this time she began to observe that it was somewhat misty around her, in the woods. She then thought that the fog must have been rising and spreading until it had reached the place where she was; and she began to be afraid that she should not be able to see across the opening, so as to find her way back to the hill, in the middle of it. She immediately attempted to go back to the opening, but she could not find her way. She soon became bewildered and lost; and the more she wandered about, the more she seemed to get entangled in the woods.

Mary did not know what to do. She sat down upon a large stone, and began to feel very anxious and unhappy. She thought that, if the sun would only shine, she could tell which way to go; for she had often observed, when she was coming up into the pasture in the morning, that she was coming away from the sun; and when she went back, it shone in her face. So she knew that if she could see the sun, and go towards it, she would soon come down near to her father's house.

She sat here for some time, but the fog seemed to grow thicker and thicker. As she was musing upon her lonely and somewhat dangerous situation, she heard a rustling in a thicket pretty near her. At first she thought it was a bear; and she was alarmed. Then she reflected that her father had told her there were no bears in his pasture, and she concluded that she would go cautiously and see what it was.

So she crept along softly, and presently began to get glimpses through the thicket. The bushes moved more and more. There was something red there; it was a cow. A moment afterwards, she came into full view of it; and behold it was May-day!

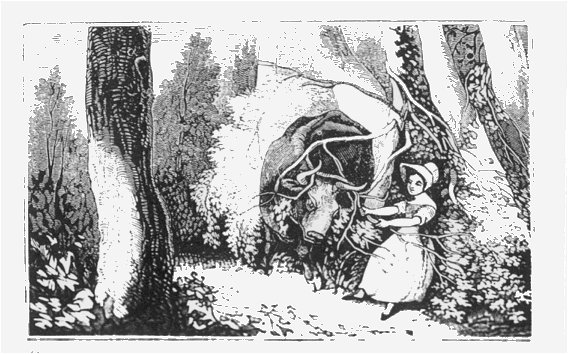

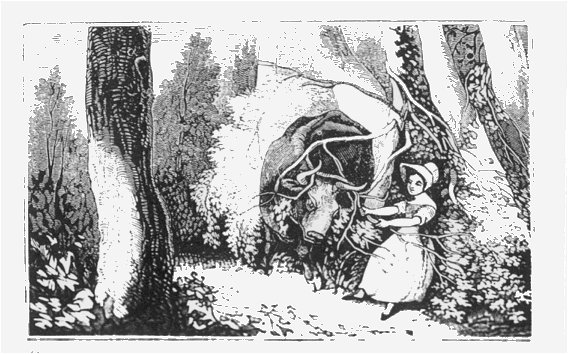

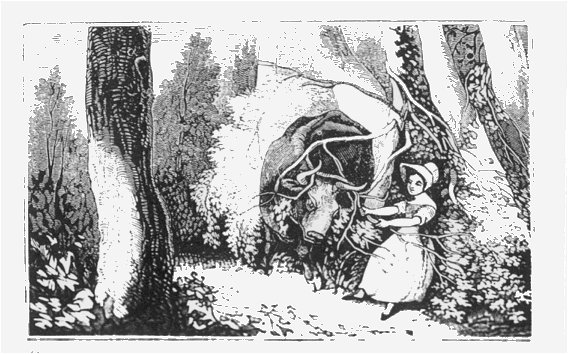

Mary was rejoiced, but she could not think what May-day was doing there; she seemed to be hooking the bushes. Mary took up a stick, and attempted to drive her out; but May-day did not move from her place,—she only stepped about a little, and hooked the bushes more than ever. This was very mysterious; and Mary came up nearer, and looked very earnestly to discover what it could mean. At length the mystery was unravelled. The cow was caught by the horns in the thicket, and could not get away. Somehow or other, in rubbing her head upon the trunk of a tree, she had got her horns locked in a sort of tangle of branches which grew there, and she could not get them out again.

At first, Mary did not see that she could do any thing herself to help the poor cow out of her difficulty, except to find her own way out of the woods as soon as possible, and get her father to come and release her. On more mature reflection, however, it seemed to her that it would be an excellent thing if she could get the cow free; for probably the cow would know the way home, and so she could herself find the way by just following her. She accordingly went nearer, in order to examine the branches, by which the horns had been entangled, more closely, so as to see if she could not do something to help the cow to extricate herself.

She found that the horns had got caught in such a way, that if the cow would move her head sideways, she could get it out,—though she could not get it out by moving it backwards or forwards, nor by working it up and down. So she determined to try to make the cow move sideways. First, however, she took hold of the end of one long branch, which helped to confine the horns, and pulled it away as far as she could; and then she contrived to got this end around behind another tree, so as to prevent its springing back. This made it easier for the cow to got out. Then she got a stick, and came around to the side of the cow, and tried to drive her. The cow pulled, and pushed, and staggered around this way and that, —every way, in fact, but the right way. Mary perceived, however, that her horns were gradually working along between the limbs, towards the place where they could get free. So she persevered. At length one horn slipped out, and the other followed immediately after; and the cow, partly through her joy at being released from her confinement, and partly from fear of the great

stick which Mary had been brandishing against her, wheeled around, and gallopped [sic] out of the thicket, tossing her horns and whisking her tail.

Mary walked along after her, in hopes that she would at once take the road which would lead home. The cow walked steadily on, and Mary soon perceived that there was something like a path where she was going. It led sometimes over grass ground, and sometimes through trees and bushes; but it all looked strange to Mary, arid the fog was so thick that she could see but a very short distance on each side of her. Once the path which the cow was taking led through a low, wet place in the woods, which looked very muddy. But Mary did not dare to stop; for she did not know what she should do to find her way out, if she should lose sight of the cow. So she pulled off her stockings and shoes as quick as possible, in order to keep them clean and dry, and then followed on, running along upon the mossy logs, and leaping from stump to stone. She got safely over; but she had not time to put on her stockings and shoes again, for fear of losing the track of the cow, and so she went on barefoot.

She proceeded in this way for some time, -- until, at length, suddenly the cow came out into a wider and better path; and in a minute or two after, she came up to a pair of bars, and stopped. Mary could not think where she was. She looked around. She could perceive the dim form of some great square building at a little distance just distinguishable through the fog. She climbed up upon the fence, to look at it more distinctly. It was her father's barn; and the house was close by. In a word, the cow had conducted her safely home. Mary could excel her altogether in contriving a way to get her horns disentangled from the branches of a tree; but she could beat Mary in finding her way out of the woods in a fog. In fact, Mary found that, though she was a very poor contriver, she was a very good guide.

CHAPTER IV.

MARY JAY.

LUCY went to a kind of a school, when she was about five years old. It was a family school; that is, a school for the children of one family, though several other children went to it. There was no large school near where Lucy lived, because there were not children enough. And so one of the families that lived near there employed a teacher to come and teach a few children. The school-room was a little back room, up stairs, over the gardener's room.

Lucy had no school to go to; and, as she had the character of being a very still, gentle, and obedient girl, the lady and gentleman who had established the family school, said that she might come and be taught with their children. Lucy was glad, for she wanted to go to school.

One of the scholars came to call for her the first day, to show her the way. It was a pleasant summer morning, and the birds were singing in the trees.

The girl that came for Lucy appeared to be a year or two older than Lucy. She came in, and sat still in the parlor while she was waiting for Lucy to get ready. Lucy's mother spoke to her several times, but she did not answer much. She seemed to be afraid.

Presently, when Lucy was ready, they went out of the door together. Lucy had her bag in her hand, with an apple and a book in it. The other girl had a bag too. She opened the gate to let Lucy go out, and then shut it after her. Lucy's mother stood at the door, and bade them good morning.

The two children took hold of each other's hands, and walked along for some minutes, without speaking a word. At length Lucy's companion said to her, timidly,

'' Isn't your name Lucy ? "

" Yes," said Lucy.

They walked along a little farther without talking, when Lucy said, with a hesitating voice,

" I don't know what your name is."

" My name is Marielle," said the other girl.

" Why, what a funny name! " said Lucy. " I never heard of any body named Marielle."

I know it," said Marielle; "and my name was Mary at first, but now they always call me Marielle."

"What for?" said Lucy.

" Why, you see," said Marielle, " that my mother's name is Mary, too; and so my father and my uncle William always called her Mary, and they called me little Mary, to distinguish. And I did not like to be called little Mary, and I told my father so."

" And then did he change your name to Marielle ? " said Lucy.

" Yes," said Marielle. " He told mother that ella or elle, was a kind of an ending that meant little, and so they called me Mariella, and now generally they call me Marielle."

" I think your name is a very pretty name," said Lucy.

" Yes," said Marielle. " I like it a great deal better than little Mary; but I don't like it perfectly well, for it means little, after all."

The children walked along by a foot path at the side of the road for some minutes after this, until at length they came to a stone wall, pretty light and smooth upon the outside, and higher than the children's heads. Branches of trees and shrubbery hung over the way from the top. Marielle said that their garden was over the other side of the wall.

" Your garden ? " said Lucy.

" Yes," said Marielle ; " and that is where we go to play in the recesses of our school."

After they had gone a little farther, Lucy found that they were coming near a house, which had a handsome yard in front, filled with trees, and shrubbery. Just before they reached this yard, there was a sort of a door, in the stone wall, very near the end of it, which Marielle suddenly opened. She stopped in herself, and then held the door open for Lucy to follow. Lucy went in, cautiously and timidly, and found herself in a long passage-way, with a smooth gravel walk beneath her feet, and a pretty green grass border on each side. Beyond the border, on one side, was the paling, or open fence, which separated the passage from the front yard of the house. On the other side was a kind of framework called a trellis, which was covered with grape-vines. Beyond the trellis was the garden.

Marielle shut the door, and latched it, after Lucy, and then said,

" We call this the door gate, and we must never leave it open, Lucy."

Then she walked along through the passage-way, and Lucy followed her. At the end of it, they came into a pleasant little yard, near the end of the house; and they passed across this yard, and thence through another gate, which was low, and made of open work. They passed through this gate, and then turned round a corner, and went along a walk with rose-bushes and snowballs upon one side, and flower-beds upon the other, until they came to a door. This door was open, and several children were sitting upon the steps, arranging flowers.

Lucy staid here a few minutes, and then they heard a little bell ring, and all the children began to run up stairs. Marielle waited to go up with Lucy, and show her the way. When they reached the top of the stalls, they turned, and went into the school-room.

Lucy thought it was a very pleasant school- room; but she did not have time to look about much, for Marielle led her directly to the teacher's table. The teacher said that she was glad to see her, and asked her to look around the room, and see where she should like to sit. Lucy looked about a little, but could not decide very well; and so she said that she should like to sit with Marielle.

" Very well," said the teacher; " is there room I at your table, Marielle ? "

Marielle said there was room; and so she led Lucy along to the comer where her seat was. There was a little table there, and a chair near it. There was also a small book-shelf upon the wall, near where Marielle kept her books, and a nail by the side of it, where she hung her bag.

Marielle brought a small chair for Lucy, and put it by the side of her table, and she hung her bag upon her nail. She told her, however, that in the recess she would go and get another nail, and drive it up upon Lucy's side of the bookshelf, so that Lucy could have a nail to herself.

Then Lucy sat down in her seat, and began to look about the room.

There were several little tables and desks in various places. Some were near the windows, and others back near the teacher's seat, which was before, the fireplace.. Upon the teacher's table there was lying a large plume, made of three or four peacock's feathers. Marielle told Lucy that when that plume was lying down, they might j all talk, but, then, when the teacher put it up in its place, at the end of the table, then it was study hours, and they must not talk at all.

There was no fire in the fireplace, because it was summer; but instead of it there was a large bouquet of flowers and shrubbery, which the children had gathered in the garden, and placed there, with the ends of the stems in a jar of water, which stood upon the hearth.

The school had not yet begun, but the children were all busy, getting their places and taking out their books. They were talking to each other very busily, but in low and gentle tones of voice. There were some boys and some girls; but they were all small children, except one. There was one pretty large girl sitting in a comer at a desk by herself. One of the small children was standing by her side talking with her. She had a round, full face, though she looked rather pale; and the expression of her face, and of her beaming blue eyes, was an expression of contentment and happiness.

Lucy asked Marielle who that great girl was, sitting in the corner; and she answered,

" Why, don't you know Mary Jay ? That is Mary Jay. You see she is - "

Just at this moment the little bell was rung at the teacher's table; and the teacher put the plume up, which was the signal for all the children to stop talking, and attend to what the teacher had to say. And so Marielle stopped, and sat back in her chair; and Lucy therefore lost the opportunity of hearing what she was going to tell her about Mary Jay. Lucy determined to ask her in the recess ; but she forgot it.

For in the recess the girls had such a joyous time running about the alleys and walks in the garden, that Lucy had no time to think of any thing [sic] else. There were several broad walks crossing each other at right angles, and shaded in part by fruit-trees, which overhung them. In one part of the garden there was a large square, covered with trees and shrubbery, and grass beneath. Here the children played hide-and-go seek, until they were tired; and then they went into a kind of a summer-house at the farther end of it, which Lucy did not see for some time, it was so hidden by foliage.

Here the children sat down together and talked a little while, and one of them asked why Mary Jay did not come. Another of the children, who had a little book in her hand, said that Mary Jay was not coming out that day, because she had a hard sum to do. The children all seemed to be sorry. Marielle said that she thought she might just as well have left her sum till after recess.

" See what a picture she painted for me! " said the little girl with a book.

So saying, she opened the book, and took out a little picture, which she had placed very carefully between the leaves. It was a very beautiful picture. There was a yard with a garden fence. and some trees hanging over it, and a dove-house in the end of a shed. There was a boy there, too, with some grains in a little basket, trying to call down the doves, to feed them. One was flying down, and the other was still standing upon the shelf in front of the dove-house, looking as if he was just ready to fly down too.

The heads of the children were immediately crowded together around the picture, and they all exclaimed that it was very beautiful.

"Is there a story to it, Jane?" said Marielle.

"Yes," said the little girl who had the picture, and whose name, it seems, was Jane. " Mary Jay said there was a story to it, but she could not tell it to me then, for there was not time. Only that dove's name," she added, pointing to the one just going to fly down, " is Bob-o'-link." \ " Bob-o'-link ! " exclaimed several voices at once, " what a name for a dove ! "

" Yes," said Jane, " because he is black and white, and so the boy called him Bob-o'-link; for a Bob-o'-link is black and white."

" I never saw a Bob-o'-link," said Lucy.

" And the other dove's name is Cooroo," continued Jane.

" My brother Royal has got some doves," said Lucy.

" Has he? " said Jane; " how many? "

" I don't know how many," said Lucy. " But one of them is white, and his name is Flake."

" Are your brother's doves pretty tame ? " said Marielle.

" Flake is pretty tame," said Lucy. " Royal can catch him whenever he wants him."

" Did not Mary Jay tell you anything more about the picture ? " said Marielle to Jane.

" No," said Jane, " but she promised that she would tell us all the story some day, out in the summer-house. Hark ! there is the bell."

The girls listened, and heard the bell ringing; and so they all began to go towards the house. As they were going up stairs to the school-room, Lucy asked Marielle why they always called Mary Jay by her whole name.

" Why don't you call her only Mary, sometimes ? " she asked.

" Why, Mary Jay is not her whole name," said Marielle. "That is only her first name. We always call her Mary Jay.'' \

" What is her whole name, then ? " said Lucy[.]

But Marielle could not answer this question; for at that moment they went into the school-room, and they saw that the plume was up, and consequently to speak would be against the law.

Lucy heard no more of Mary Jay until she went home from school ; and then, when she was giving an account of her adventures at school to Miss Anne and Royal, and was describing Mary Jay, and ended by saying,

" And, Royal, you don't know what beautiful pictures she can paint."

" I wish I could see some of them," said . Royal.

" I don't understand," said Miss Anne, " how so old a scholar happens to go to your school. She can't belong to the family. I don't believe that she is really a scholar there."

"Yes she is," said Lucy; " she does sums."

" How do you know? " said Royal.

"Because," said Lucy, " that was the reason why she could not come out in the recess."

" How old should you think she was, Lucy ? " said Miss Anne.

"Why, about twenty-or forty, at least," said Lucy.

Royal burst into a loud and boisterous fit of laughter at this estimate; while Lucy herself looked ashamed and perplexed, and said,

" You need not laugh, Royal; for, at any rate, she is older than you."

Royal only laughed the more at this; - even Miss Anne smiled, and Lucy, perceiving it, began to look seriously troubled. Miss Anne attempted to turn her thoughts away from the subject, by asking her how she liked her school. Lucy said she liked it very much indeed.

" I wish I could go to your school," said Royal.

" 0 no," said Miss Anne, " you are too large."

'' I am not so large as Mary Jay," said Royal, " according to Lucy's story."

" I don't understand about Mary Jay's case." said Miss Anne, " I confess. There seems to be some mystery about it. Rut I certainly should not think that they would be willing to have a boy as old as you in their school,-unless he was a very remarkable boy indeed."

"Why not?" said Royal.

" Because," said Miss Anne, "it is a private school, opening into a very valuable garden; and, of course, all the fruit and flowers are exposed."

" No, not all," said Lucy; " there is only a part of the garden that we can go in."

" How do you know ? " said Royal.

" Why, I was walking along with Marielle, and I wanted to run down a winding walk by the great pear-tree, and Marielle said we must not go there."

" What great pear-tree ? " said Royal.

" 0, a great pear-tree there was there."

" Couldn't you go there at all ? " said Royal.

" Not unless the teacher went with us," said Lucy, " or else Mary Jay. At least, that is what Marielle said."

The children talked no more about the school at this time, but Miss Anne said that she meant to ask Lucy's mother about Mary Jay; for she wanted very much to know how there came to be so large a scholar in such a little school.

All this account of Mary Jay is given here, because Lucy afterwards learned more about her, and heard her tell a number of stories, some of which are given, farther on in this book. But Lucy did not learn anything more about her that day, nor hear any of her stories. But she heard one story that afternoon from her father.

He told it to her, while he was sitting in a chai [sic] in the yard behind the house, looking towards Royal's hen coop. It was the story of the Old Polander. This story is given in the next chapter.

Back to main page

Scanned for

19th-Century Girls' Series;

please do not use on other sites without permission