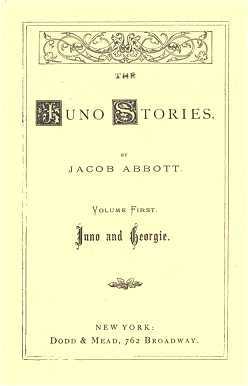

Juno and Georgie

INTRODUCTION

TO THE JUNO STORIES.

THERE is a great deal of instruction called religious, which is not really religious in any proper sense, though in other aspects of it it may be very excellent and useful.

A mother, for example, gives her children on Sunday afternoon a lesson in the catechism to learn, and she requires them to remain isolated from each other and silent, for half an hour, that they may study it. When, finally, they come to recite the lesson she asks George the question, "What is sin?"

George replies, fluently and correctly, " Sin is any want of conformity to, or transgression of, the law of God."

Now this, if properly managed, even if nothing is said in explanation of the meaning of the language, may be a very useful exercise for George and the others. It gives them practice in silent, solitary study,-helps to form in them habits of self-control, and of mental concentration,-exercises and trains their vocal organs and their memory,-and thus in many ways advances their cerebral and mental development.

But this kind of instruction is not, in any proper sense, religious. It does not touch the heart with any religious sentiment. It does not reach the heart at all. It does not even, on the supposition made that no explanations are given, reach the intellect.

The exercise may moreover take such a form that the intellect may be reached and enlightened, and the heart still not touched at all. For example, the mother may say:

To conform means to fit to, to agree with. If a stair-carpet were to be laid loosely upon a staircase so as to touch only the edges of the steps, it is plain that it would not conform to the steps. To make it conform to them it must be fitted in, at each step, so that you could go up and down upon them. Transgression means passing over. Egression means passing out. Digression means passing aside. Transgression means a wrongful passing over. If I should draw a twine string from one stake to another in the garden, to guard my flower-bed, and the children should step over it, that would be a transgression,-it would be a wrongful passing over of a line. It would be the same if I were only to give a command, instead of stretching a line. In that case walking on my flower-bed would be a transgression of the command.

The mother might continue her explanation in this vein until the children fully comprehended the meaning of the answer which they had learned. She would say that one of the laws of God was that people should be just and kind to each other, and that consequently if a boy were to have an apple, or a cake, given to him to be divided between himself and his brother, and were to cut it so as to take the biggest portion for himself, his conduct would not be in conformity with, that is it would not agree with, the law of God,-but would on the contrary be a transgression of it.

In this way the understandings of the children, instead of merely their vocal organs and their memories, would be reached and cultivated. The effect would consequently be of a higher character and of greater value in this second case than in the first. Still the heart, if touched at all, would only be influenced indirectly and incidentally, since the whole direct end and aim of the instruction in such a case is to make clear to the intellect the true meaning and import of the language.

But there is a third mode,-or rather a third stage in the process. The mother, after having required the children to learn their lesson well, and having explained to them fully the import of the language, may tell them a story, the tendency of which should be to find an entrance for the lesson to their hearts. It requires no incentive genius to frame such a story. She has only to describe a boy of the age of one of her auditors, to give him an attractive personal character, to picture details of the house where he lived, the room where he slept, and the playthings that he had, so as to fill the imaginations of the children with agreeable images, or awaken in their minds an interest in the boy, and thus predispose them to sympathize with him in his ideas and feelings. She then represents the mother of the boy as giving him a cake to take out into the garden, and there, at a pretty seat in a corner among the lilies and roses, to divide it between himself and his little sister Julia. The boy divides it, and observing that there is a slight difference between the two portions, gives Julia the largest part, and. that too when Julia is too little to observe or to know the difference, so that he does this not to prevent Julia from complaining, but simply for the sake of doing right, of obeying the divine law, and pleasing his Heavenly Father. Now most children in hearing such a story will feel a strong sympathy with the boy, in the sentiment of justice and generosity which actuated him, and will be made more or less inclined to feel and act in a similar way under similar circumstances; and this sympathy will be strengthened in proportion as the scene of the story, and the person and character of the boy are made attractive by agreeable and entertaining details. At any rate the influence of such an exercise, whether more or less attractive, is one intended, not to act primarily upon the memory, or upon the understanding, but directly upon the heart.

Now it is action of this nature which it is the design of these stories to illustrate, and which is the only kind of influence which truly deserves the name of religious training.

It ought perhaps to be added, that a certain portion of the matter contained in the first two volumes has been already, to some extent, .communicated to the public in another form.

JACOB ABBOTT.

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION. .................... ....... ............... 5

I. A REMARKABLE PHENOMENON. .......................... 11

II. IN THE GARDEN......................................... 27

III. JUNO'S TACT. ......................................... . 40

IV. JUNO'S STORY OF THE LITTLE HYPOCRITE .............. 63

V. JUNO'S STORY OF JIPSIE AND JIP. ....................... 64

VI. JUNO'S AQUARIUM....................................... 75

VII. JUNO'S WAY OF ANSWERING QUESTIONS ................. 89

VIII. JUNO'S STORY OF MOSES IN THE BULRUSHES ............ 99

IX. JUNO IN THE SUMMER-HOUSE........................... 111

X. JUNO'S MODE OF TEACHING OBEDIENCE ................. 135

XI. JUNO'S MODE OF PLAYING A LESSON..... ............... 137

XII. JUNO AND TOMMY.. ............................. ....... 150

XIII. JUNO AND MARY 0SBORNE.............................. 165

XIV. JUNO'S FIRST DAY. ...................................... 179

XV. JUNO'S DARK HOUR.......... .......................... 191

XVI. JUNO IS NOT DlSCOURAGED............................. 201

XVII. JUNO WILL NOT DISCOURAGE HER SCHOLARS............. S13

XVIII. JUNO'S LOST SHEEP RECOVERED. ....................... 288

XIX. JUNO AND THE VERY BAD BOY. ........................ 241

XX. MANAGEMENT OF DICK. ................................. 254

XXI. TELLING STORIES....................................... 267

XXII. STORY FOR DAVY. ...................................... 280

XXIII. JUNO'S THIRD LESSON .................................. 290

XXIV. CONTINUING THE STORY...... .......................... 3O1

On to chapter one

Back to main page

Scanned by Deidre Johnson for her

19th-Century Girls' Series website;

please do not use on other sites without permission