Ellen Linn

PREFACE.

-«---»-

THE development of the moral sentiments in the human heart, in early life,-and every thing in fact which relates to the formation of character,-is determined in a far greater degree by sympathy, and by the influence of example, than by formal precepts and didactic instruction. If a boy hears his father speaking kindly to a robin in the spring,-welcoming its coming and offering it food,-there arises at once in his own mind a feeling of kindness toward the bird, and toward all the animal creation, which is produced by a sort of sympathetic action, a power somewhat similar to what in physical philosophy is called induction. On the other hand, if the father, instead of feeding the bird, goes eagerly for a gun, in order that he may shoot it, the boy will sympathize in that desire, and growing up under such an influence, there will be gradually formed within him, through the mysterious tendency of the youthful heart to vibrate in unison with hearts that are near, a disposition to kill and destroy all helpless beings that come within his power. There is is no need of any formal instruction in either case. Of a thousand children brought up under the former of the above-described influences, nearly every one, when he sees a bird, will wish to go and get crumbs to feed it, while in the latter case, nearly every one will just as certainly look for a stone. Thus the growing up in the right atmosphere, rather than the receiving of the right instruction, is the condition which t [sic] is most important to secure, in plans for forming the characters of children.

It is in accordance with this philosophy that these stories, though written mainly with a view to their moral influence on the hearts and dispositions of the readers, contain very little formal exhortation and instruction. They present quiet and peaceful pictures of happy domestic life, portraying generally such conduct, and expressing such sentiments and feelings, as it is desirable to exhibit and express in the presence of children.

The books, however, will be found, perhaps, after all, to be useful mainly in entertaining and amusing the youthful readers who may peruse them, as the writing of them has been the amusement and recreation of the author in the intervals of more serious pursuits.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I.-DISASTER, ...... 11

ll.-THE FOUR RULES, ...... 39

III.-BEECHNUT, ...... 59

IV.-DISCIPLINE, ...... 80

V.- RODOLPHUS, ...... 103

VI.-RODOLPHUS AT THE MILL, ...... 114

VII.-THE RETURN, ...... 134

VIII.-THE DIVING PIER, ...... 151

IX.-THE HAY CAMP, ...... 173

X.- AGNES, ...... 192

ENGRAVINGS. PAGE

HOUSE WHERE ELLEN LIVED-FRONTISPIECE.

FARMER TYNE'S, . . . . . 25

THE SHELTER, . . . . . . ..33

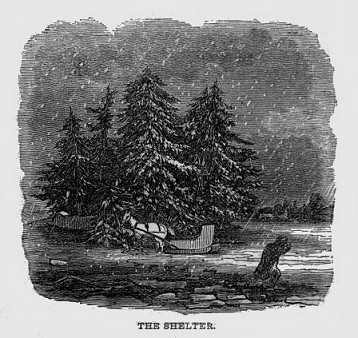

THE PICTURE, . . . . . .64

THE RESCUE, . . . . . . .. 70

ANNIE'S PRISON, . . . . . . .81

ANNIE AT THE FIRE,. . . . . . . 101

THE RENDEZVOUS, . . . . . . .117

ELLEN, . . . . . 128

RODOLPHUS AT THE MILL., . . . . .131

THE SHOES, . . . . . 151

THE PIER, . . . . . 171

THE GREEN BANK, . . . . . ..183

THE HAY CAMP, . . . . . 190

FRANCONIA STORIES.

ORDER OF THE VOLUMES. | MALLEVILLE. | RODOLPHUS. |

| WALLACE. | ELLEN LINN. |

| MARY ERSKINE. | STUYVESANT |

| MARY BELL. | CAROLINE. |

| BEECHNUT. | AGNES. |

SCENE OF THE STORY.

FRANCONIA, a village among the mountains at the North, The time is in the spring and summer.

PRINCIPAL PERSONS.

ELLEN LINN.

RODOLPHUS, her brother.

MRS. HENRY, a lady residing at a short distance from the village at Franconia.

ALPHONZO, commonly called Phonny, her son; now about ten years old.

MALLEVILLE, Mrs. Henry's niece, about eight years old.

ANTOINE BIANCHINETTE, a French boy, at service at Mrs. Henry's, now about fourteen years old. He is commonly called Beechnut.

MARY BELL, Ellen Linn's friend.

ELLEN LINN.

CHAPTER I..

DISASTER.

ELLEN LINN'S father and mother lived in a small, but very pleasant house, by the side of a mill-stream, just below the village at Franconia. Ellen herself, however, did not live at home much, while she was a child. She lived with her Aunt Randon, in. a farmhouse among the mountains, a mile or two from. her father's house. Her brother and sister, however, Rodolphus and Annie, lived at home.

When Ellen's aunt died, Ellen came to live at home again. Her father died at the same time. He got lost in the snow in. a great storm, and perished.

It was in the night that Ellen's father got lost in the storm-a night in February. The storm began the night before ; the children, Rodolphus and. Annie, when they woke up in the morning, found that it was snowing.

" There! it is snowing," said Rodolphus, " and I am glad of it."

" Why are you glad ?" said Annie.

" Because we can't go to school to-day," said Rodolphus.

" And I am sorry, for that very account," said Annie.

Annie was quite a little girl, much younger than Rodolphus, but she liked to go to school.

The storm increased all the morning. About ten o'clock, Rodolphus and Annie were playing together in the kitchen. Rodolphus had got a pudding pan from one of the shelves of the dresser, and having turned it upside down upon the floor, was trying to stand on his head upon it. He attempted to steady himself by clasping the sides of the pudding pan with his hands. Annie was seated on a block by the side of the fire, attempting to draw upon her slate. She was much distressed to see Rodolphus trying such dangerous experiments.

"Rodolphus!" said she, in a very stern voice, " you must not do so. You will break your head,-or else the pudding pan."

Just then the outer door opened, and Rodolphus, fearing that his father might be coming in, suddenly jumped up and put the pudding-pan upon the table. He just had time to do this, and to assume a countenance of innocence and unconcern, when the inner door opened, and his father came in.

Thus Annie's prediction, that Rodolphus would break either his head or the pudding-pan, failed of accomplishment; and there was not, in fact, much danger of his breaking either, for they were both very strong. He, however, brought upon himself another kind of suffering by thus doing what he supposed his father would disapprove, that is, he made himself feel guilty and self-condemned, and so very miserable, when his father came in. The guilty feeling is the most uncomfortable and wretched feeling that we can admit into our hearts.

Rodolphus saw that his father was muffled up as if he were going away somewhere.

" Where are you going, father ?" said he.

"I am going across the river," said his father.

"May I go, too?" said Rodolphus.

Rodolphus's question came too late for an answer; for his father was going out through another door, at the instant of Rodolphus's asking it, and he shut the door before he had time to reply.

" No, you can not go, Rodolphus," said Annie.

" Why not ?" asked Rodolphus.

' Because it is a storm," said Annie.

" No matter for that," said Rodolphus, " I can go if it does storm."

"No" said Annie, " or else you might have gone to school."

"Hoh!" said Rodolphus, "that's a different thing."

Very soon after this, Mr. Linn came back again, he was looking for his whip. He was not accustomed to have regular places for his things, and so he often lost them ; that is, he laid down any thing that he had been using, wherever it happened to be convenient for the moment, and then when he wanted it again, it was often nowhere to be found.

"What can have become of my whip ?" said lie, impatiently. " Rodolphus, what have you done with my whip?"

"I have not had your whip" said Rodolphus.

Mr. Linn, as other persons who lose their property by their own carelessness are apt to do, often charged the loss unreasonably upon others, and Rodolphus in cases where he was thus charged, often replied to his father very disrespectfully.

" Let us go and see if we can find the whip," said Annie,-in a low and gentle tone.

Rodolphus sat still, but Annie went to look for the whip. Presently Mr. Linn, who was all the time looking about for the whip, demanded of Rodolphus why he had not gone to school. Rodolphus said it was on account of the storm, and then he asked his father to let him go with him over the river.

"No," said his father, "you ought to have gone to school."

Just at this moment Annie found the whip. It was behind the clock. Rodolphus had put it there. His father had laid it down upon the kitchen table when he came in with it the last time, and Rodolphus had taken it to play horses with it, and when he was tired of playing horses, he had hid the whip away behind the clock, so as to have it ready whenever he should want it to play with again.

"That's a good girl," said Mr. Linn, when

Annie brought out the whip. " You may go over the river with me if you please."

" Well," said Annie, clapping her hands. " I'll go and get my bonnet."

Just then, however, Mr. Linn looked at the clock, and seeing how late it was, said that on the whole he would wait till after dinner, as he found that there would not be time to go and come back before dinner. He accordingly waited. It was after one o'clock before he was ready to go. The storm, in the mean time, had increased, and the snow was getting to be very deep. Annie's mother began to be afraid to have Annie go. "It is a dreadful storm," said she, " I am almost afraid to have your father go himself." But Mr. Linn said there was no danger, he should get home, he said, before the snow became very deep. This did not satisfy Mrs. Linn, but she yielded and began to dress Annie far the ride. She put a warm cloak over her, and tied a woolen comforter about her neck ; and then her father, taking her up in his arms at the step of the door, carried her out to the sleigh, and getting in himself he rode out of the yard.

Annie covered herself up well with the buffalo skins which were in. the sleigh, leaving only a small opening to peep out at. She called this her peeping hole. It did not, however, do much good, for when Annie peeped out there was little to be seen but the storm.

The house where Mr. Linn lived was situated, as has already been said, on the bank of a small stream a little below the village. This stream emptied into a pretty broad river about a mile below. Mr. Linn was going across this river. Accordingly when he got into the road, instead of taking the way which led toward the village, he turned in an opposite direction, that is to say down the stream.

" Where are you going, father ?" said Annie.

" Over the river," replied her father.

There seemed to be something terrible to Annie's mind in the idea of going over the river in such a storm, though she knew very well that the whole surface of the water was frozen over, and that the ice was very thick and very solid. She could not but think, however, what a dreadful thing it would be, if by any possibility they should break through the ice and sink into the dark cold water below.

The horse trotted merily [sic] along, though the Bound of the bells was somewhat muffled by the effect of the falling snow. The wind was behind them when they turned to go down the stream, and so Annie could look out better than before, for now the wind and snow did not blow in her face. She could see the little wreaths of snow driving along the roadside, and the walls half covered, and the trees -wherever trees grew along the bank of the stream-with their dark ever-green branches whitened with flakes and bent down with the load that rested upon them.

After going on in this way for a short distance, Mr. Linn stopped the horse.

" What are you stopping for ?" asked Annie.

" To speak to a man," said her father. As her father said these words, Annie heard the sound of sleigh bells coming up a steep road, or rather up a steep place where it seemed as if there might be a road, though every thing was so buried up in snow that all traces of a traveled way bad wholly disappeared. Annie pushed her buffalo aside and looked out. She saw a horse and sleigh coming up. Mr. Linn remained where he was until the man came near, and then asked him if the road was blocked up much, down on the ice.

"No," said the man, without stopping, and so passed by.

" Then I am going down upon the ice," said Mr. Linn. So saying he turned down into the way by which Annie had seen the man ascending.

Annie thought that she should be afraid when the horse and sleigh began to go upon. the ice, but she was not, for she did not know when it was. For after descending the hill, and riding along for some distance-all the way through deep snow-she asked her father how long it would be before he would come to the ice.

"We are on the ice now," said he, "and we have been upon it for a long time."

Annie looked out eagerly at hearing this. She saw that they were riding over what seemed to be a long and narrow field, all white with snow. This she knew was the stream. She could see the banks on either side, though very dimly, on account of the air being full of driving snow. Presently they came to the mouth of the stream, and then keeping directly onward they began to go out on the broad river.

Annie now soon lost sight of the land altogether. Nothing was to be seen on either hand but the thick and. murky atmosphere. She expected that the horse's back would have been covered with snow, but it was not. White lines were seen here and there in sheltered places among the harness, but the snow was so dry, and it was driven so freely by the wind, that very little remained where it fell.

Annie was somewhat afraid now. She thought of the deep and black water which she knew was gliding along beneath them, under the ice, and began to imagine the awful condition that she and her father would be in, if the ice should break through. She wished that her father would talk to her, but he was very silent. She asked him several questions from time to time, but he answered very briefly and then relapsed into silence, as before. So at last she covered up her head with the buffalos, and asked her father to tell her when they got to the land.

" We have got to it now," said her father. Annie immediately looked out, and saw a dim, dark mass rising up before her. It proved to be the edge of the forest, on the bank. The road entered this forest as it left the ice, and as soon as the sleigh was fairly sheltered by the trees, the wind seemed suddenly to subside, and the air became calm.

" How much farther is it ?" asked Annie.

" About a mile," replied her father.

" Where is it that you are going ?" said Annie.

" To Farmer Tyne's," replied her father.

There was another man whose name was Tyne living in that neighborhood, who was a carpenter, and so the man to whose house Mr. Linn was now going was generally called Farmer Tyne to distinguish him.

" What are you going for?" asked Annie.

" To get some corn," said Mr. Linn.

" Oh!" said Annie.

Then after a short pause she added,

" And how are you going to bring it home?"

"In a bag," said her father.

" Where is the bag ?" asked Annie.

" Down in the bottom of the sleigh," replied her father.

" Oh !" said Annie again.

It took nearly half an hour to go to Farmer Tyne's house from the river, although the distance was only about a mile, for the snow was so deep that the horse was obliged to walk almost all the way. At one place, they came to a drift so deep that the horse could not get through it, and Mr. Linn was obliged to get out of the sleigh and trample down the snow, around and before the horse.

When Mr. Linn got into the sleigh again, Annie asked him which was the strongest, a man or a horse.

" A horse, certainly," said Mr. Linn.

" Then why can not he trample down the snow himself, as well as to have you get out and do it for him ?"

"I don't know, child," said Mr. Linn, "you must not keep asking me so many questions."

Being thus repulsed, Annie was silent during the remainder of the ride, excepting that at one time, when they were going up a long hill, she sung a little song to herself, keeping time with the jingling of the sleigh-bells, which came to her ear in a sort of regular beat, as the horse walked slowly along.

At length Annie found herself riding into a yard. She thought that it was Farmer Tyne's yard, but she did not dare to inquire, for her father had. directed her not to ask questions. She was right, however, in her conjecture, for it was Farmer Tyne's yard.

Mr. Linn stopped at a door in a sheltered corner, round behind the house, he lifted Annie out of the sleigh, and then opening the door, he set her down in a sort of passage Just then an inner-door opened, and a little child appeared. The child had come in order to see who it was that had arrived.

" Where's your father, Jenny ?" said Mr. Linn, speaking to the child.

"He is out in the barn," said Jenny.

"Well, take Annie in by the fire," said Mr. Linn, " while I go and find him. I shall come back presently."

So Jenny came forward, and taking Annie by the hand, she led her in.

Annie found herself ushered into a very comfortable farmer's kitchen. The walls were darkened by time, and the windows were so much obscured by the snow which was banked up against them on the outside, that there was not much light in the room, except what came from the fire. There was, however, a very bright, blazing fire, which gleamed over the floor, and diffused its light and its warmth all about, so as to make the room look very comfortable and pleasant.

There was a very old woman sitting in an old-fashioned rocking-chair in one corner. She was knitting, rocking at the same time a very little to and fro. She listened when Annie came in, but she did not look up. In fact, it would have done no good for her to look up, for she was blind. She, therefore, only listened.

Annie went up to the fire, and Jenny brought her a chair.

The hearth was formed of two very large flat stones. These bad been originally one stone, but the fire had cracked it, and the two parts had become somewhat separated, so that now there were two.

The fireplace was built of stones, too. These stones were rough and irregular in form, and laid together like a common wall, without any mortar between them. Annie liked the fireplace very much, and she wished that they had such an one at their house.

There was an apple down upon the hearth, between the andirons, roasting. Jenny pointed to it and said,

"I have just put an apple down to roast for me, and now I will go and get another and put it down for you."

So she lighted a candle and went down cellar, and presently returned with a very large rod-apple for Annie. Jenny put the candle away, and then set Annie's apple down upon the hearth by the side of her own.

As soon as she had done this, the old woman in the rocking-chair called her.

" Jenny ?" said she.

"What, grandmother?" said Jenny.

"Who is that that has come in ?" asked the old woman.

"Annie Linn," said Jenny.

So the old woman went on with her knitting.

The children watched the apples a few minutes, and then went playing about the room.

After a few minutes the old woman said again,

" Jenny, who is this that has come in to play with you ?"

" Annie Linn," said Jenny.

So Jenny's grandmother went on with her knitting again.

"You told her once before," said Annie to Jenny in a whisper.

"Yes, but she always forgets," said Jenny, " may be she'll ask me again pretty soon."

But she did not ask again, for before she took it into her head to do so, Mr. Linn came in to tell Annie that he was ready to go home.

Annie was quite surprised and disappointed to find that the time had come for them to go home.

" Now, father !" she exclaimed in a mournful tone. " My apple is not roasted yet."

Mr. Linn looked at the apples as they stood on the hearth before the fire, and said he thought they were roasted enough.

" Besides, I wanted to eat my apple," said Annie.

" Very well," said Mr. Linn, " eat it now. I will wait for you to do that."

" But it is too hot," said Annie.

While this conversation had been going on, Jenny had brought a plate and a fork, and began to take up the apples.

" Then you must carry it home and eat it there," said Mr. Linn.

" But it will burn my fingers to carry it," said Annie.

" Well," said Mr. Linn, "I don't know what you will do, then, for we must not wait here any longer. The storm is growing worse and worse, and the snow is getting so deep that I don't know whether we can get home even if we go now, and I can't wait any longer."

Jenny contrived a plan to escape from the difficulty. She went into a closet and brought out an old tea-cup. It was perfectly clean, though it was cracked, and there was a notch broken out in the edge on one side. She put Annie's apple in this cup. The apple was so large that it filled the cup full. Jenny then went to a drawer and took out a piece of white paper, and this she put over the apple in the cup, and then wrapped up the whole in a cloth. By this time Annie had put on her cloak and bonnet, and was ready to go Jenny put the round parcel that she had made into Annie's hands, just as her father was taking her up to carry her out to the sleigh, saying,

"There, hold it so, and it will keep your hands warm all the way home."

So Annie said good-by to Jenny's grandmother and to Jenny herself, and then Mr. Linn carried her out into the storm. The wind was blowing very high, and it whirled the sharp, driving flakes of snow so furiously through the air, that Annie covered her face up entirely when her father put her into the sleigh. Her father then spread a great buffalo-skin over her. Here she remained a long time, wholly hidden from view. She could perceive that she was moving along through the snow, and could feel the warmth of her apple in her hands. She could also hear the muffled jingling of the bells, and the howling of the winds in the tops of the forest, and that was all. She rode so for a long time.

Several times the sleigh stopped, and Mr. Linn got out, and after doing something about the horse, he would come back, get into the sleigh again, and drive on. Annie supposed that there were great drifts at those places, and that her father got out to trample down the snow, so that the horse could get through. But she did not like to ask any questions.

She peeped out now and then, but she found that it was growing dark very fast. It made Annie afraid, to see that it was growing dark, and so she determined not to look out any more. She therefore covered herself up entirely in the buffalos, and comforted herself as well as she could with feeling the warmth of her apple, as she held the parcel in her hands.

After some little time, she observed that the horse went more and more slowly. Her father had to whip him and to shout out to him continually, to make him go along. He got out very often, too, to trample down the snow.

At length the horse stopped, and Mr. Linn allowed him to stand still, for a minute or two, he himself remaining in his seat by the side of Annie. Annie opened the buffalo-skin and peeped out.

"What's the matter, father?" said she.

" I don't know where we are," said her father.

Annie pushed away the buffalo-skin entirely, and looked around. It was quite dark. Nothing was to he seen but the white snow close around the sleigh, and the flakes falling thick through the air.

" What shall we do then ?" asked Annie.

" I don't know," said her father, " cover yourself up. All that you have to do, is to cover yourself up, and keep yourself warm."

So Annie covered herself up. In a minute she -felt the sleigh moving again. Her father was driving on. After going a short distance, her father called out, in a joyful tone,

" Ah! here we are."

" Where ?" said Annie, pushing open the buffalo-skin. " Let me see."

" Here's the land," said her father.

" Why, have we been on the river ?" said Annie.

" Yes," said her father, " and here's the land."

Annie beheld a small dark mass of trees before her, dimly seen through the falling snow.

Mr. Linn supposed that he had got across the river, and that this land was the shore near his house ; but he was mistaken. He had lost his way, and had gone down the river more than a mile, and the land which he bad now discovered was a small island, at a great distance from either shore.

As soon as he discovered his mistake, he seemed to be in great distress and perplexity.

"I don't know what I shall do," said he.

"Where are we?" said Annie.

" Why, we are a mile down the river, and I don't think the horse can ever get us back again. I shall have to find some shelter for you, and leave you here while I go across to the shore and get some help."

" Well," said Annie. " I can stay."

Mr. Linn drove round to the lower side of the island, and there he found a sort of cove which formed a sheltered nook among the trees, just large enough for the horse and sleigh. He led the horse into this recess, and tied him with along rein to a small tree, which grew near the shore. He then covered the horse with a blanket. Next he went to the sleigh, and directed Annie to creel down into the bottom of it, while he covered her up with the buffalo-skin. Annie did so. The bottom of the sleigh was covered with straw, and the bag of corn lay upon one side, so that by lying down upon the straw, and putting her head upon the bag of corn for a pillow, Annie contrived to place herself in a very comfort able position.

Mr. Linn then put two buffalo-skins over her, tucking the edges of them down all around on the inside of the sleigh very carefully. There was a third skin, but this, Mr. Linn thought, would not be necessary, and so he threw it over the back of the sleigh, he thought that Annie would be stifled if he were to cover her up too much.

" Are you comfortable ?" said Mr. Linn, putting his head down near the sleigh and speaking very loud.

"Yes, sir," said Annie.

" And warm enough ?"

"Yes, sir," said Annie.

" Can you breathe well ?" said Mr. Linn.

"Yes, sir," said Annie.

" Very well, lie still then, till I come back. I shall come in the course of an hour."

So Mr. Linn left the sleigh, and turning from the island, he began to force his way

through the deep snow, in the direction which he supposed led toward the shore.

It was not long before Annie began to find it rather difficult to breathe, under her coverings, for the heavy buffalo-skins lay down close to her face, and the air was very close and confined. She soon remedied this difficulty, however, by means of her father's whip. Her father had given her this whip to take care of, before he had covered her up ; the whip had

a short and very stiff handle, and Annie found that she could push up the middle of the buffalo-skins with one end of it, and then keep them up by resting the other end of the whip- handle on the bottom of the sleigh. Thus she made a sort of tent, though yet the buffalo-skins were lifted only a very little by tills contrivance. They were raised enough, however, to give Annie plenty of air to breathe.

She lay quite still for a little while, listening every moment for her father's return. At length, however, she began to grow sleepy, and in fact within half an hour of the time that her father left her, she was fast asleep.

After a time she waked again. She did not know how long she had been asleep. She was not quite sure that she had been asleep at all. She thought she would push up one corner of the buffalo coverings which had been placed over her and peep out. She did so. She saw the horse standing quietly in his place,-the trees loaded with snow, and above, the moon was shining through broken clouds that were floating in the sky.

" The storm is over," said Annie, "now my father will come pretty soon."

Annie began to think that she was hungry.

She wished that she had something to eat. She thought first of the corn in the bag, and she wished very much that it was parched corn. If it had been parched corn, she thought that she would have untied the bag and got some of it to eat. Then she recollected her apple. She felt for it among the straw around, her, and soon found it there. It had fallen out of her hand while she had been asleep. She soon contrived to get the paper off, and then holding the cup in her hands, bit a small hole in the skin of the apple, and sucked the pulp all out. Then leaving the core and the skin in the cup, she wrapped the paper around them again, and pushed the whole into a corner of the sleigh, as far away as possible. She laid her head down again upon the bag of corn, and began to sing a little tune. In a few minutes she sang her self to sleep. She slept for many hours.

In the mean time morning came. The people in the village and in the farm-houses of the country around, rose from their beds, and finding that the storm was over, they opened their doors and windows, and began to shovel off the banks of snow from their door-steps, and to make paths. After breakfast, they started out in different directions with teams of oxen, to break out the roads. One of these parties passed by Mr. Linn's house, and were surprised to find the doors all shut, and the snow around the house unbroken, as if there were no one at home. A young man with a shovel in his hand waded through the deep snow up to the door of the house, and knocked on the door very loud, with the handle of his shovel, he could not get any answer. The men then went on and inquired at the next house. They were told that Mr. Linn and Annie had gone across the river the day before, and were to have come home in the evening; and that Mrs. Linn and Rodolphus had gone afterward up to see Mrs. Randon, who was very sick, and not expected to live through the night. The people were alarmed at these tidings. They sent some men with a team to break a road over the river, and see if Mr. Linn was at Farmer Tyne's. The men accordingly went. Farmer Tyne told them that Mr. Linn and Annie were not there. They had set out to return home in the storm, he said, about sunset the day before.

The men were now still more alarmed. Farmer Tyne said that he would go with them, to see what had become of Mr. Linn and Annie. The whole party accordingly went back to the river. After searching about for some time, one of the men espied something black on the surface of the snow at a great distance down the river. They all proceeded to the spot, and were dreadfully shocked on arriving there, to find that the black spot was a part of Mr. Linn's arm, and that his body was beneath, frozen and buried up in the snow.

The men took up the body in solemn silence, and put it upon the sled, and then while a part of them proceeded with it toward the shore, the others set off in various directions to find the horse and sleigh, and Annie. They soon discovered the sleigh in the shelter where Mr. Linn had placed it. The man who first saw it shouted out, and the rest all came eagerly to the spot. They lifted up the buffalo and found Annie within.

" Why, Annie, are you here ?" said one of the men.

" Yes," said Annie, " but where is my father?"

" Your father," said the man, " your father -why--he has gone home."

Here there was a moment's pause. At length the man said again,

" Poor child, we may as well tell you first as last. Your father is dead."

" Dead !" said Annie.

" Yes," said the man, " he got lost in the snow."

Annie was silent a moment, as if she scarcely understood the words, and then she exclaimed in a tone of bitter anguish,

"Oh dear me! -what shall I do?"-and burst into tears.

It was thus that Annie lost her father.

CHAPTER II.

THE FOUR RULES.

ON the same afternoon that Annie and her father took their ride across the river, to Farmer Tyne's, a messenger came down from the house where Annie's sister Ellen was living with her aunt among the mountains, to say that Ellen's aunt, whose name was Mrs. Randon, was very dangerously sick, and to ask that Mr. and Mrs. Linn would go up and see her. As Mr. Linn was away, Mrs. Linn at first did not know what to do. She finally concluded to go to Mrs. Randon's in a sleigh with the messenger, and to take Rodolphus with her. She met with various difficulties and adventures in the storm on the way, but at length she reached Mrs. Randon's in safety. Mrs. Randon had died however before she arrived. The result of Mrs. Randon's death was that Annie's sister Ellen came home to live with her mother again, so that in one short week, a double change was made in Annie's condition. Her sister was restored to her, and her father was taken away.

Annie was a girl of very mild and gentle disposition, but she was not at all obedient to her mother. Her mother in fact had taught her to be disobedient-not intentionally indeed, but incidentally, by her mode of management. When she gave Annie commands she did not insist upon her obeying them, as she ought to have done; and in cases where Annie openly disobeyed her, if no evil consequences happened, she let the case pass without taking any notice of the transgression.

For instance, one day Rodolphus was making a vane to put up on a corner of the shed, and in the course of his operations, he fixed a ladder against the shed in order that he might climb up to the roof. When he had got the ladder placed, he mounted upon it, Annie standing all the time below, and looking on with great curiosity and wonder. As soon as Rodolphus had safely reached the roof, he called to Annie who was on the ground below,

" Come up here, Annie."

Annie looked up the ladder, and then advancing to the foot of it she took hold of the rounds and began to step up from one to the other. The shed was not very high, and she was soon half-way up the ladder.

Just then her mother came to the door and called out to her very earnestly, saying :

" Why Annie, you must not go up that ladder. Come down immediately."

" Come right up quick," said Rodolphus, in an under-tone. He was standing on the shed at the top of the ladder, looking down to Annie, as he said this.

" Come right up quick," said he, " she will not care."

" Come down, Annie, immediately," said her mother.

But Annie remained where she was, without obeying either of the contradictory orders which had been addressed to her. She looked up to Rodolphus to see how much farther she had to go to reach the top. Then she looked toward her mother and began to beg for permission to go on.

" Ah ! yes, mother," said she, " do let me go on. I am almost to the top."

" No," said her mother, " you will fall. Come down immediately, if you do not, I shall certainly punish you."

Mrs. Linn pronounced the word certainly in a very emphatic manner.

" No, mother, I shall not fall," said Annie. Rodolphus did not fall. See! mother," she added, "see how well I can go up." So saving she stepped very carefully up another round.

" Come right up," said Rodolphus.

" See ! mother," said Annie, stepping up another round.

By this time Annie had got so far that Rodolphus could reach her arm. he extended his arm down to help her mount.

'' Take care," said Mrs. Linn, " go very carefully."

So Annie, with Rodolphus's help, reached the roof of the shed and stepped over safely upon it.

" And now how are you ever going to get down ?" asked Mrs. Linn.

" Oh I will help her down, mother," said Rodolphus, " you need not be at all concerned."

" Well," said Mrs. Linn. " Only be very careful not to go near the edge of the shed, Annie, and not stay up a great while."

So Mrs. Linn went back into the house.

Of course such a mode of proceeding as this was the best possible mode to teach both Rodolphus and Annie to be habitually disobedient to their mother's commands,

It was in a somewhat similar way that Mrs. Linn taught Annie to persist in importuning, or as she called it, teasing her mother, when she wished for any favor or indulgence which her mother was at first unwilling to grant. Her mother would first absolutely refuse. Annie would, however, go on urging her request, and her mother would refuse again, though less decidedly than before. This would, of course, encourage Annie to persevere, and then her mother would begin to argue the case, giving reasons why she could not grant the request. These reasons would, of course, be wholly unsatisfactory to Annie, and so she would argue back in reply, and thus in the end her mother would give a hesitating and reluctant consent to Annie's request.

For instance, one day pretty late in the fall of the year in which Mr. Linn perished in the storm, Annie came into the kitchen where her mother was ironing at a table near the window, and began, to look about for her bonnet and shawl. She had no regular place for putting these things, and so whenever she wished to use them, she was obliged to look about in closets and drawers, wherever she thought there was any chance that they might be found.

" Mother," said Annie, " what has become of my bonnet and my shawl ? I can not find them anywhere."

Her mother asked her what she wanted them for, and where she was going.

Annie said that she was going down. to the shore with Rodolphus.

There was a stream of water, as has already been explained, that flowed along in front of the house where Annie lived, on the other side of the road from the house. There was a high bank between the road and this stream, with steps to go down. Below, along the margin of the water, was a pebbly beach where Rodolphus and Annie were very fond of going to play. They called it going down to the shore.

" No, Annie," said Mrs. Linn, " you must not go down to the shore to-day."

"Ah! yes, mother," said Annie, "let me go. Rodolphus is going, and I want to go very much."

"No," said her mother, " I think you had better not go."

" But, mother," said Annie, " Rodolphus is going, and I want to go very much."

" But it is very cold," said Mrs. Linn. " I would not go if I were you. Besides, I am afraid you will fall into the water. Stay at home with me, that's a good girl. You will have a great deal better time in staying here with me by a good fire."

Annie was not at all convinced by these arguments, so her mother directed her to go and look in the back-room, and perhaps she would find her bonnet and shawl there. As soon as Annie went out, Mrs. Linn opened a cupboard and took out Annie's bonnet and shawl, which she had known all the time to be there, and stepping hastily across the room where there stood a large old-fashioned clock, she opened the door of the case below, and putting the bonnet and shawl in, she hid them securely there. She had just time to shut the, door, and go back to her work again, when Annie came in, saying, in a mournful tone, that she could not find her bonnet and shawl, and she did not know what she should do. Mrs. Linn went on very busily with her work, and said nothing, Annie, however, soon perceived something peculiar in the expression of her mother's face, and came up to her, saying:

" Now, mother, you know where my bonnet and shawl are, I verily believe."

Mrs. Linn said nothing, but ironed away, in a very energetic manner.

"Now, mother !" said Annie, in a tone of mournful entreaty. " You know where my bonnet and shawl are, I am sure."

A lurking smile now appeared on Mrs. Linn's face, though she said nothing, and went on ironing, as before.

" Mother !" said Annie, " why can't yon tell me where my bonnet and shawl are ?"

Mrs. Linn put her flat-iron down and went to the clock. She opened the door and took the shawl and bonnet out, saying:

" There, I suppose I shall have to let you go, or else I shall have no peace. But you must not stay long, and don't go near the water."

So Annie put on her bonnet and shawl and rail off, saying, as she went: " No;, I will be very careful."

Of course, nothing could be better contrived to teach a child to tease and importune her mother, where her requests were denied, than such a mode as this, of drawing her into a contest, and allowing her the victory in the end.

By these, and similar modes of management, Annie, though naturally a very amiable, gentle and affectionate child, had gradually lost all sense of subordination to her mother's authority. She was careless and negligent in all her duties; her room and her drawers were in constant disorder, and she was gradually becoming impatient of every species of control. In fact, Annie was in a fair way of being spoiled.

When Ellen came home to her mother's, after the death of her aunt, she was for many days very disconsolate. The contrast was so great, between the condition, of things at her aunt's and at her mother's, that she thought at first, that she never could be happy at home. She walked about the house, lonely and sad She mourned the death of her father and of her aunt, and was homesick to go back to the happy fireside among the mountains, where she had lived so long.

At last, one day, about a week after the funeral of her father, she had been helping her mother in her work in the kitchen all the afternoon, and was just thinking that it was time to begin to get supper, when Annie came into the room, looking weary and forlorn, and said that she wished that Ellen would give her something to do. Ellen was sitting at the time, by the side of the fire, looking into the embers, and thinking of the happy days that were past, now never to return. Her eyes were full of tears. Annie came up to her, and leaning against her lap, looked up into her face and said,

" Ellen, I wish you. would not be so unhappy."

Ellen took Annie up into her lap.

" How can I help it, Annie dear ?" she said.

" I don't know," said Annie, " but I wish you would help it somehow or other."

" Well, I will," said Ellen. " I have been unhappy long enough, and I will not be unhappy any more. Come, you shall help me get supper."

"Well!" said Annie. Her face brightened up as she spoke, with an expression of great pleasure.

" The first thing," said Ellen, "is to build a good fire."

.So Ellen and Annie went together out into the shed to get some wood. Ellen let Annie bring in a part, while she, herself, brought the remainder. She allowed Annie to help her in placing the wood on the fire. She could have done it more easily herself alone, but she saw that it pleased her sister to be permitted to help her. Then Annie swept up the hearth, and put the furniture in order in the room, while Ellen began to set the table. In half an hour the whole expression of the room. was changed, and as Ellen went about her work in a joyous and happy manner, talking playfully with Annie all the time, Annie soon became as blithe and gay as she was wont to be. Even Mrs. Linn, herself, who had been overwhelmed with depression and sorrow, began to look more cheerful than she had done at any time, since her husband's death.

From this time, every thing improved very rapidly at Mrs. Linn's. Ellen employed herself, every day, in putting some new room or closet of the house in order. At first, she undertook only such work in this respect, as she. and Annie could manage, and was very careful to do nothing without first obtaining her mother's approval. After a time, however, her mother began to be so much pleased, with the results which Ellen produced, that she began to help her in her work, and to propose new undertakings,-until at last, in the course of a fortnight, the whole house seemed to be renovated from top to bottom. A great quantity of useless rubbish was brought out and burned; articles of clothing were arranged, places for utensils were determined upon- nails being driven up at convenient points for such as would hang, and shelves designated. for the rest. In a word, the whole house gradually assumed such an appearance of neatness and order, that Annie said it seemed exactly like her Aunt Randon's.

One afternoon in March, Ellen and Annie made a fire in the chamber where they slept, intending to put every thing in order there. This room was an attic room of course, for the house was only one story high. It was, however, a very pleasant room, and it had a window in it. This window looked toward the great gate which led out of the yard to .the road. After working a long time, and putting every thing in order in the room, Ellen and Annie stopped to rest. They went together to the window, and Ellen sat down in a straight-back rocking chair, which stood there, and took Annie in her lap; and both began to take a survey of the room.

In one side of the room there was a small fireplace, where the fire which the children had made was still burning. There was a closet by the side of the fireplace, with drawers and shelves in it, all of which were now nicely arranged. Opposite to the fireplace, and not very far from it, for the room was small, was a bed. By the side of the bed, stood a table with a looking-glass upon it. The table was covered with a white cloth. On the other side of the table was a blue chest, which belonged to Annie. Her father had made it for her. There was a trunk in the room, too, near the door. This trunk belonged to Ellen. She had brought it home with her from her Aunt Randon's. There were several pictures in plain frames hanging on the walls of the room, and in one corner was a small set of hanging-shelves with several books upon them.

As Annie took her seat upon Ellen's lap, she looked around the room a minute or two with a smile upon her face, and then said,

" How pleasant it looks!"

" Yes," said Ellen, " we have put the room in order. The difficulty is now to keep it in order."

Here there was a pause. Annie was thinking that that would be no difficulty at all.

"There is one thing more," said Ellen. "Now that I have come back to live at home again, I shall wish to have you become a very excellent, good girl."

"Yes," said Annie, "I will." Then after a moment's pause she added, " but how shall I do it ?"

"Why, the first thing is," said Ellen, "that you must always obey mother."

"Yes," said Annie, "I do. But Rodolphus does not obey her. He is very disobedient. I think Rodolphus is very disobedient indeed."

" But you. do not always obey mother yourself," said Ellen, " she is sometimes obliged to speak to you a great many times before you obey her."

"Well, that is because she does not make me obey her," said Annie. " I should obey her if she would make me."

" What sort of a plan would it be," said Ellen, "for you to be my girl, and obey me ?'

" Well," said Annie.

" And that makes me think," said Ellen, " of Aunt Randon's rules. They are in my trunk."

So Ellen put Annie down from her lap and went to her trunk, Annie going with her. While she was unlocking and opening her trunk, Annie went on with the conversation.

" I should like to be your girl very much indeed," said Annie, "and I will always obey you exactly."

" But the first command that I should give you," said Ellen, " would be, that you should always obey mother."

By this time Ellen had opened her trunk, and reaching down to the bottom of it, she took out a small square picture frame, about as large in length and breadth as the palm of a man's hand.

The frame itself was of some dark-colored wood, highly polished. There was a glass in . it, and under the glass there was a paper with a small picture above and something printed below. The picture was a very pretty one. On the left, there was a lady sitting under a tree, in a wild place on the border of a wood, reading Before her there was a beautiful place to play,-smooth and green, in the middle, with safe rocks to climb up upon on one side, and a great many flowers. There were two young children playing here. They were running about upon the grass, climbing up the rocks, and gathering flowers. Beyond this little green where the children were at play, opposite to where their mother was reading, and of course on the right-hand side of the picture, there was an awful precipice

which overhung a torrent that was to be seen tumbling and foaming over the rocks below.

The meaning of the picture was, that these children were perfectly safe, though they were playing so near the brink of the precipice, and their mother could read without giving herself any concern about them, simply because they were obedient. She had told them how far they might go, and was confident that they would confine themselves strictly to the limits which she had assigned them.

The printing under this picture was as follows :-

THE FOUR RULES.

When you consent, consent cordially;

When you refuse, refuse finally.

Commend often: never scold.

Annie began to read these rules, and though she proceeded slowly and with difficulty, she at length came to the end.

"What does it all mean?" said she.

"They are Aunt Randon's rules," said Ellen. "They show what I must do, to take care of you, if you are going to be my girl."

" How ?" said Annie; and so she began to read the rules over again, one by one, for Ellen to explain them.

" When, you consent, consent cordially," said Annie, reading,

"That means," said Ellen, "that when you come to ask me to let you go anywhere, or do any thing, I must not answer hastily, but consider the objections first myself, and if I think on the whole that I will let you go, I must say "yes" willingly, without troubling you about the objections. For instance, if you ask me to let you go out and play some day when you are not very well, and I consider that on the whole I should be willing to let you go, I must not say, ' Why, Annie, I would not go if I were you. You are not well, and perhaps you might take cold; and, besides, it is not very pleasant. But still you may go, if you wish to go very much.' "

" What must you say, then ?" said Annie.

"I must say, 'Yes, I think it will be safe; and you will have a very good time, I have no doubt. You must be dressed warm, and then I think there will be no danger.' "

" Yes," said Annie, " I would a great deal rather that you would say that."

"That is what my Aunt Randon used to say."

" And now the next rule," said Annie.

So Annie went on to read the next rule as follows,

" When you refuse, refuse finally."

" And. what does that mean ?" said she.

"It means," replied Ellen, "that if, after thinking of the subject, I conclude that it is not best for you to go, and once say so, that must end the matter. You must not ask me any more to let you go,-and if you do, I must not alter my decision."

Annie was silent. She hardly knew what to think of such a rule as this.

" How do you like that rule?" said Ellen.

"Pretty well," said Annie, "but not so well as the other."

Annie then proceeded to read the third rule.

" Commend often: never scold."

"That's a good rule," said Annie. "I don't like to be scolded. but what does commend mean ?"

"It means praise-not exactly praise either. it means that if you try to be a good girl, I must be pleased with you, and let you see that I am pleased."

" Yes," said Anne, " I think that is a good rule. They are all good rules; and it is a beautiful picture at the top of them."

"Yes," said Ellen, "and I think it is a very pretty frame. Beechnut made this frame."

"Did he?" said Annie. "Beechnut lives at Mrs. Henry's."

"Yes," said Ellen, "he used to come up and see me sometimes at Aunt Randon's."

Mrs. Henry's house was about a mile from the place where Annie lived:-beyond the village. Ellen's Aunt Randon's was still further off, among the mountains. Annie and her brother Rodolphus sometimes stopped at Mrs. Henry's to see Beechnut, and Phonny, Mrs. Henry's son, on their way to their aunt's. So Annie knew Beechnut very well.

It happened singularly enough, that while Ellen and Annie were thus talking about Beechnut, they heard a sound in the yard as if some one were opening the great gate, and on looking out the window, they saw Beechnut himself and Phonny, in a wagon, coming in.

Annie jumped down from Ellen 's lap and ran to meet the visitors. Ellen followed, going more slowly but not less joyously. How it happened that Beechnut came just at this juncture will be explained in the next chapter.

On to chapter 3

Return to main page