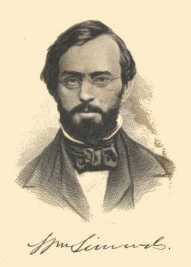

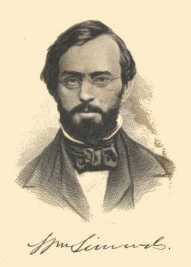

William Simonds (Walter Aimwell)

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, on October 30, 1822, Simonds was the third of

four sons. His father died when he was about six, and, soon after, the family moved to Salem,

where Simonds attended school until he was thirteen. Following his mother's remarriage, he was

apprenticed to a jeweler for several years, and then, in 1837, to a Boston printer.

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, on October 30, 1822, Simonds was the third of

four sons. His father died when he was about six, and, soon after, the family moved to Salem,

where Simonds attended school until he was thirteen. Following his mother's remarriage, he was

apprenticed to a jeweler for several years, and then, in 1837, to a Boston printer.

During this period, Simonds honed his writing skills by keeping a

journal in which he practised writing brief essays

on a variety of topics. (One of the final entries for 1838 -- when he

was only sixteen -- was a six-page

summary and commentary on a lecture he had attended.)

In 1846, Simonds began his own magazine, the Boston Sunday

Rambler (later absorbed into the New England Farmer).

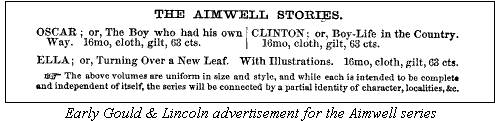

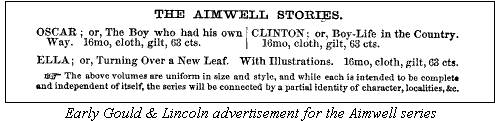

Simonds published several instructive books for children,

such as The Boy's Own Guide (1851) and The Boy's Book of

Morals and Manners (1852), before beginning the first book in

what became The Aimwell Stories (so titled

because it was published under the pseudonym Walter Aimwell -- an

early example of a juvenile author selecting a name reflective of

themes in his work).

The series has a somewhat unusual publishing history, since

the second book, Clinton, was actually published first.

After completing Clinton, Simonds supposedly brought the

manuscript to Boston, where he walked to the door of publishers

Gould & Lincoln and then withdrew, instead opting to mail the

manuscript to them. They returned it, saying it was too short, but

that if he chose to lengthen it, they'd be willing to publish it.

Clinton debuted on Christmas Eve day, 1853. Simonds began

writing the next volume, Oscar, on March 2, 1854,

and it appeared in December of that year. Despite its publication date,

Oscar is always listed in ads as the series' first volume,

presumably because its events precede those in Clinton.

The series followed a formula introduced in Jacob Abbott's

Franconia books, where each volume

bore the title of a different character and focused on his or her

activities, but incorporated characters from other volumes.

Like other books of the period, the Aimwell series

was heavily didactic:

ads explained that the stories were "designed to portray some of

the leading phases of juvenile behavior and to point out their

tendencies to future good and evil." Two entries from Simonds's journal

indicate his philosophy "I must strive to become an eminent Christian. . . .

I must do good as well as be good, and I must labor to have

those around me enjoy the same spiritual blessings that I do."

A brief summary of the series demonstrates both its didactic

nature and the method whereby Simonds was able to

weave a story through multiple volumes and still foreground

a different character in each volume. In Oscar; or, The Boy Who

Had His Own Way, Oscar, "a headstrong, wayward boy," progresses

from being "disobedient and disregardful of the wishes of his mother"

to more serious wrongdoing. In an attempt to surround him with

beneficial influences, his parents send him to the country for volume

two, Clinton; or, Boy Life in the Country, where Oscar meets the title

character but continues his downward slide, ultimately "join[ing] a

band of juvenile thieves and ending up in reform school." Volume

three, Ella; or, Turning Over a New Leaf, focuses on Oscar's

younger sister, Ella, as she struggles to curb her own impulsive

nature. The end of her story prepares readers for both the fourth

and the fifth volumes while also connecting the material with earlier

titles: As a reward for her good behavior, Ella's parents allow her

an extended visit to a country estate, accompanied by a boy named

Whistler, a relative of Clinton. Their country adventures are related

in volume four, Whistler; or, The Manly Boy.

A brief summary of the series demonstrates both its didactic

nature and the method whereby Simonds was able to

weave a story through multiple volumes and still foreground

a different character in each volume. In Oscar; or, The Boy Who

Had His Own Way, Oscar, "a headstrong, wayward boy," progresses

from being "disobedient and disregardful of the wishes of his mother"

to more serious wrongdoing. In an attempt to surround him with

beneficial influences, his parents send him to the country for volume

two, Clinton; or, Boy Life in the Country, where Oscar meets the title

character but continues his downward slide, ultimately "join[ing] a

band of juvenile thieves and ending up in reform school." Volume

three, Ella; or, Turning Over a New Leaf, focuses on Oscar's

younger sister, Ella, as she struggles to curb her own impulsive

nature. The end of her story prepares readers for both the fourth

and the fifth volumes while also connecting the material with earlier

titles: As a reward for her good behavior, Ella's parents allow her

an extended visit to a country estate, accompanied by a boy named

Whistler, a relative of Clinton. Their country adventures are related

in volume four, Whistler; or, The Manly Boy.

Oscar and Ella's parents also decide to send Oscar to another

country village, this time entrusting him to Marcus, a paragon of

virtue who'd had remarkable success in molding boys' characters, and

the fifth volume, Marcus; or, The Boy Tamer, chronicles Oscar's

gradual reform as well as Marcus's positive effect on other young

boys. Interwoven in the tale is the sad story of a neighboring

family, whose indolent father gradually falls into ruin and dies in

disgrace, leaving a widow and two children. One of them, Jessie,

is taken in by the family with whom Oscar and Marcus board and

becomes the central character of the next volume, Jessie; or, Trying To Be Somebody,

as she tries to better herself and keep her younger brother

out of trouble. By then, Oscar has become an upstanding young man

and befriends Jessie and her brother.

While series ads noted that "Each volume . . . [was]

complete and independent of itself [with] a connecting thread

[running] through the series," the series strategy was obviously

designed to encourage readers to buy all six titles; moreover, when

characters from previous books were mentioned, a footnote would refer

readers to the appropriate books for more information--a marketing

strategy that other series authors later appropriated.

Simonds was apparently quite intrigued by the fictional community

he had created. One biographical sketch notes that he had recorded

each character's birthday in a notebook, and on a pocket map, had

"marked the very spot where the incidents [in one book] are supposed

to occur." Simonds died on July 7, 1859, before completing the series.

The last volume he worked on, Jerry, was published posthumously

as an unfinished tale, and he had plans for at least

five other volumes.

Biographical Sources

"Simonds, William." National Cyclopedia of American Biography. Vol. 5.

Aimwell, Walter. [Simonds, William.] Jerry; or, The Sailor Boy Ashore; To Which Is Added a Memoir

of the Author with a Likeness. (Lincoln & Gould, 1863).

Return to main page

Copyright 1999-2000 by Deidre Johnson

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, on October 30, 1822, Simonds was the third of

four sons. His father died when he was about six, and, soon after, the family moved to Salem,

where Simonds attended school until he was thirteen. Following his mother's remarriage, he was

apprenticed to a jeweler for several years, and then, in 1837, to a Boston printer.

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, on October 30, 1822, Simonds was the third of

four sons. His father died when he was about six, and, soon after, the family moved to Salem,

where Simonds attended school until he was thirteen. Following his mother's remarriage, he was

apprenticed to a jeweler for several years, and then, in 1837, to a Boston printer.  A brief summary of the series demonstrates both its didactic

nature and the method whereby Simonds was able to

weave a story through multiple volumes and still foreground

a different character in each volume. In Oscar; or, The Boy Who

Had His Own Way, Oscar, "a headstrong, wayward boy," progresses

from being "disobedient and disregardful of the wishes of his mother"

to more serious wrongdoing. In an attempt to surround him with

beneficial influences, his parents send him to the country for volume

two, Clinton; or, Boy Life in the Country, where Oscar meets the title

character but continues his downward slide, ultimately "join[ing] a

band of juvenile thieves and ending up in reform school." Volume

three, Ella; or, Turning Over a New Leaf, focuses on Oscar's

younger sister, Ella, as she struggles to curb her own impulsive

nature. The end of her story prepares readers for both the fourth

and the fifth volumes while also connecting the material with earlier

titles: As a reward for her good behavior, Ella's parents allow her

an extended visit to a country estate, accompanied by a boy named

Whistler, a relative of Clinton. Their country adventures are related

in volume four, Whistler; or, The Manly Boy.

A brief summary of the series demonstrates both its didactic

nature and the method whereby Simonds was able to

weave a story through multiple volumes and still foreground

a different character in each volume. In Oscar; or, The Boy Who

Had His Own Way, Oscar, "a headstrong, wayward boy," progresses

from being "disobedient and disregardful of the wishes of his mother"

to more serious wrongdoing. In an attempt to surround him with

beneficial influences, his parents send him to the country for volume

two, Clinton; or, Boy Life in the Country, where Oscar meets the title

character but continues his downward slide, ultimately "join[ing] a

band of juvenile thieves and ending up in reform school." Volume

three, Ella; or, Turning Over a New Leaf, focuses on Oscar's

younger sister, Ella, as she struggles to curb her own impulsive

nature. The end of her story prepares readers for both the fourth

and the fifth volumes while also connecting the material with earlier

titles: As a reward for her good behavior, Ella's parents allow her

an extended visit to a country estate, accompanied by a boy named

Whistler, a relative of Clinton. Their country adventures are related

in volume four, Whistler; or, The Manly Boy.