Copyright 2018 by Deidre Johnson . Please do not reproduce without permission

The man responsible for writing the first fictional series for children, for introducing many of the key types and techniques of series books, for popularizing the genre virtually single-handedly, and for writing some of the earliest American juveniles deserving of the term "children's literature" was the multi-talented Jacob Abbott. Born 14 November 1803 in Hallowell, Maine, Abbot was the second of seven children (and the eldest son) of Jacob and Lydia Abbot. Abbot's parents were, according to his brother John, "the strictest class of Christians," who impressed upon their children the importance of a Christian life and who were "loved [by their children] with a fervor that could hardly be surpassed." [1] Jacob spent a happy childhood in Hallowell, where he and his brothers all attended Hallowell Academy. All five Abbot sons followed strikingly similar paths; as one biographer notes, "all five graduated from Bowdoin College, all studied theology at Andover, all became teachers and ministers; all became authors except the youngest [Samuel] who died in 1849." [2] This background is reflected in Abbott's works, which are imbued with his religious, moral, and educational beliefs, and which contain numerous scenes depicting happy, productive children.

Abbott graduated from Bowdoin in 1820. At some point during his years there, he supposedly added the second t to his surname, to avoid being "Jacob Abbot the 3rd" (although one source notes he did not actually begin signing his name with two ts until several years later).[3] After graduation, he taught at Portland Academy -- where one of his pupils was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow -- and studied theology at Andover. In 1824, he began as a tutor at Amherst College, and by 1825 or 1826, was Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy there. In 1826, he was also ordained, and, thereafter, in addition to teaching, occasionally gave sermons in the college chapel.

On May 18, 1828, Jacob Abbott and Harriet Vaughan married; the following year, he

and his brother John

founded

Mt. Vernon School, a high school for girls, which opened in Boston in June 1829.

One of his pupils

was Elizabeth Stuart Phelps (who later wrote another of the

earliest girls' series, Kitty Brown). The sixteen-year-old Stuart lived with the Abbott family while attending school and "published her first stories in a magazine edited by Abbott." [4] While at Mt. Vernon, Abbott

saw his first books published, including The Young Christian; or, A Familiar Illustration

of the Principles of Christian Duty (1832), "intended to explain and illustrate,

in a simple manner, the principles of Christian duty . . . not . . . exclusively for

the young, but for all who are just commencing a religious life, and who feel desirous

of receiving a familiar explanation of the first principles of piety."

[5]

In 1834, Abbott left Mt. Vernon and moved to Roxbury, where he accepted

the pastorate

of a Congregational

Church. The following year, he published what became the first of

the Rollo

series, The Little Scholar

Learning to Talk. A Picture

Book for Rollo (later reissued as Rollo Learning

to Talk). The

book originated when a book

agent "unearthed an assortment of engravings which he thought

could be

used as [book] illustrations" and

showed them to Abbott, who worked them into book form.[6]

The second Rollo book was

published the same year, with others added to the

series in subsequent years, for a total of fourteen

volumes.

In 1836 or 1837, Abbott resigned his pastorate for health reasons and returned to Maine with his family, wintering in his father's house in Farmington. He bought land across the street and built a home, "Little Blue," so dubbed "because of a hillock upon it whimsically named [by Abbott] after the loftier Mt. Blue twenty miles to the north." [7] There he continued to write, beginning the Jonas books in 1840, featuring a character who had appeared in the Rollo books as an occasional guide and mentor for Rollo. As Abbott explained in the preface to Jonas on a Farm in Summer, the books were

all designed, not merely to interest and a muse the juvenile reader, but to give him instruction, by exemplifying the principles of honest integrity, and plain practical good sense, in their application to the ordinary circumstances of childhood.

The prefatory note to another volume in the series, Caleb in the Country, expanded the series' goals, explaining "Caleb, and the others of its family, will include also religious training, according to the evangelical views of Christian truth which the author has been accustomed to entertain, and which he has inculcated in his more serious writings."

Abbott's first girls' series, the Lucy books, featuring Rollo's young cousin (who had already played a role in Rollo's series) appeared the following year, with goals similar to those of her predecessors. A notice at the front of the book read:

The simple delineations of the ordinary incidents and feelings which characterize childhood, that are contained in the Rollo Books, having been found of interest, and, as the author hopes, in some degree to benefit the young readers for whom they were designed, -- the plan is herein extended to children of the other sex. . . . the author hopes that the history of [Lucy's] life and adventures may be entertaining to the sisters of the boys who have honored the Rollo books with their approval.

After his wife's death in 1843, Abbott moved to New York, where, with his brothers John and

Gorham, he

founded the Abbott Institute (originally called the New Seminary for Young Ladies),

which provided "more

advanced academic training than was usually available" for girls.[8]

In 1843, he also

began the six-volume Marco Paul series. The preface of Marco Paul in

New York explained the works were designed "to communicate . . . as extensive and varied information as

possible, in respect to the geography, the scenery, the customs and the institutions of this country, as

they present themselves to the observation of the little traveler, who makes his excursions under the

guidance of an intelligent and well-informed companion." "This country" was rather narrowly defined, as

Marco Paul ("a boy about twelve years old") never ventured beyond New York and New England, but it served

as a prelude to future travelogue series.

In 1848, Abbott took the first of many trips to Europe,

later drawing on his travels for

a new Rollo series, the ten-volume Rollo's

Tour in Europe (1853-58), in which twelve-year-old Rollo, like Marco Paul, journeyed under the

protection and supervision of a wise companion (in this case, his uncle, Mr. George). Abbott also remarried

in November

1853, to Mary Woodbury. During this period, Jacob and his brother John wrote a series

of "Illustrated Histories" (1848-54), biographies of historical

figures such as Alexander

the Great, Cleopatra, Ghengis Khan, and Elizabeth I, intended for adolescents.

Jacob authored twenty-two of

the thirty-two volumes in the series.

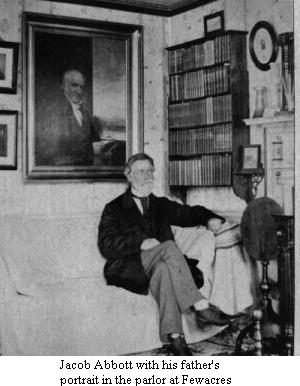

Around 1870, Jacob Abbott again returned to Farmington, this time to live in "Fewacres," his father's former house, since "Little Blue" was now a boarding school. He died 6 November 1879. He had written 180 books and edited or co-authored an additional 31. [9] Two of his four sons, Edward and Lyman, later wrote biographical sketches of their father, the former in a special 1882 edition of Jacob Abbott's The Young Christian; the latter, in his own Silhouettes of My Contemporaries.

Abbott's children's series, especially his ten-volume Franconia stories (1850-54) have been praised for their depiction of children and their approach to storytelling. In an analysis of Abbott's Rollo books, William Lawrence characterizes Abbott's educational philosophy as a belief in "discipline . . . tempered with sympathy and understanding of a child's point of view," adding that Abbott "loved boys and girls -- perhaps the ultimate secret of his popularity." Lawrence observes that while Abbott was "much concerned with morals and instruction" -- as he had to be, writing for children in the early nineteenth century -- he nonetheless "made his tales plausible and true to life. The simple world . . . he pictured was one which any child could accept." [10] In a survey of Abbott's juvenile fiction, Carol Gay notes that the characters in the Franconia stories have been considered to be "the first realistic, three-dimensional characters to appear in American children's literature," [11] an assessment echoed by children's literature historian Corneila Meigs, who characterizes the series as a "delightful set of simple narratives of young people . . . living the uncomplicated and unrestricted life of little town and broad country, with all the small adventures and larger crises of a child's life." [12] Perhaps the best assessment of Abbott comes from Gillian Avery, who, after discussing Abbott's writing within the context of its age, concludes by observing, "His writing has a rare humanity, tolerance, and gentleness which makes it stand out among children's books of any age." [13]

1. Quoted in Lysla Abbott. "Jacob Abbott: A Goodly Heritage, 1803-1879." In The Hewins Lectures 1947-1962. Ed. Siri Andrews. Horn Book, Inc., 1963.

2. Lysla Abbott. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Online biographical sketch at Bedford/St.Martin's.

5. Jacob Abbott. "Introduction." The Young Christian; or, A Familiar Illustration of the Principles of Christian Duty. Rev. ed. American Tract Society, 1832.

6. G. Silver Rollo. "Rollo on Rollo." The Colophon. New Graphic Series. No. 2. 1939.

7. Jennie Lawrence Pratt. "Jacob Abbott." In Just Maine Folks by The Maine Writers Research Club, 1924.

8. Carol Gay. "Jacob Abbott." Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 42. For an account of Abbott and the school by George Root, its music instructor, click here.

9. For a bibliography of Abbott's works, see Pat Pflieger's excellent Nineteenth-century American Children and What They Read pages. That site also contains etexts of two of the Rollo books, Rollo Learning to Read and Rollo's Travels, and several of Abbott's other books. For a detailed study of the printing history of Abbott's books, with numerous illustrations and commentary, see Cary Sternick's impressive Jacob Abbott website.

10. William W. Lawrence. "Rollo and His Uncle George." New England Quarterly, September, 1945. For librarian Caroline M. Hewins' memories of Abbott's Lucy series, click here.

11. Carol Gay. "Jacob Abbott." Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 42.

12. Cornelia Meigs, et al. A Critical History of Children's Literature. Rev. ed. Macmillan, 1969.

13. Gillian Avery. Behold the Child: American Children and Their Books, 1621-1922. Bodley Head, 1994.

Abbott, Jacob. Young Christian: A Memorial Edition. Harper, 1882. [Includes biographical sketch by Edward Abbott.]

Abbott, Lyman. Silhouettes of My Contemporaries. Doubleday, Page, 1922.

Click here to read Lyman Abbott's biography of

his

father (from Silhouettes); the chapter includes material on Abbott's books and educational philosophy

Abbott, Lysla. "Jacob Abbott: A Goodly Heritage, 1803-1879." In The Hewins Lectures 1947-1962.

Ed. Siri Andrews. Horn Book, Inc., 1963.

Avery, Gillian. Behold the Child: American Children and

Their Books, 1621-1922. Bodley Head, 1994.

Gay, Carol. "Jacob Abbott." Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 42.

Johnson, Deidre. "From Abbott to Animorphs, from Godly Books to Goosebumps: The Nineteenth-Century Origins of Contemporary Series." Illinois Librarians' Association Conference. October 1997.

Lawrence, William W. "Rollo and His Uncle George." New England Quarterly, September, 1945.

Meigs, Cornelia, et al. A Critical History of Children's Literature. Rev. ed. Macmillan, 1969.

Osgood, Fletcher. "Jacob Abbott, A Neglected New England Author." New England Magazine, June, 1904.

Pratt, Jennie Lawrence. "Jacob Abbott." In Just Maine Folks by The Maine Writers Research Club, 1924.

Rollo, G. Silver. "Rollo on Rollo." The Colophon. New Graphic Series. No. 2. 1939.

Titcomb, Mary. "A Delightful Grandfather." Wide-Awake Magazine, February, 1882.

For a complete list of Abbott works available online, see the Abbott links page as well as the two series pages -- Abbott's girls series and Abbott's Boys', Non-Fiction, and Miscellaneous Series.