Joanna Hone Mathews and Julia Anton Mathews (Alice Gray)

Despite their popularity and success as a children's authors, Joanna and Julia Mathews

received almost no publicity or biographical attention during or after their lifetimes. While Joanna's

accomplishments -- more than fifty children's books and novels -- earned her inclusion in the first volume

of Who's Who in America in 1899, two years later her New York Times obituary devoted almost

one-fourth of its space to recounting her late father's achievements instead.[1]

Julia's death twenty years earlier had not even received that much notice.

The Mathews sisters were born into an illustrious family. Their father, Reverend James

Macfarlane (sometimes spelled McFarlane or McFarland) Mathews (1785-1870) served as minister of the

Presbyterian South Dutch Church in New York City from 1811-40. During his tenure there, he helped found

the University of the City of New York (now New York University) and reigned, somewhat tumultously, as

its first chancellor from 1831 until his resignation in 1839. He then served on the University's Advisory

Council until 1847; over the next two decades, he published several scholarly works and reminiscences.

Ann Hone (1805-87), Joanna and Julia's mother, was the daughter of a prosperous merchant and the niece

of a former mayor of the city.[2]

The limited information about Joanna and Julia's childhoods indicates that they grew up as

part of a large, affluent household. James McFarlane married his first wife in 1810 and already had

three daughters from that union when he remarried in 1825; his second marriage, to Ann Hone, resulted

in ten additional children (one of whom died in infancy). Joanna was their firstborn; Julia, the eighth.[3]

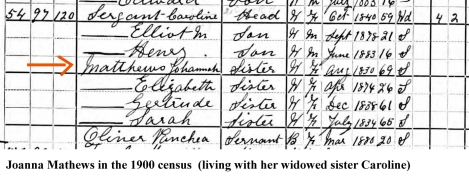

Although Joanna's birthdate is often shown as 1849 (presumably from an error in her entry in Who's Who),

she was actually born between 1827 and 1830.[4] Julia was born about 1836.

Joanna was educated at Madame Reichard's French Boarding and Day School in New York;[5]

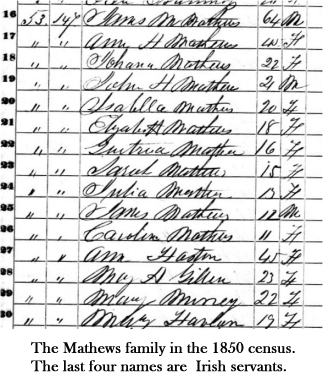

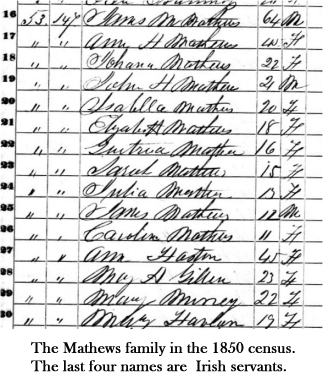

no information about Julia's background has been located, though the 1850 census verifies she attended school

that year. The 1850 census also established that all nine of James and Ann Mathews's children

(seven daughters, two sons, ranging in ages from eleven to twenty-two) were still living at home

and that the household included four Irish servants. James, listed as a clergyman, owned property valued at

$10,000; his eldest son, John was a clerk. Ten years later, the 1860 census revealed the

value of James's McFarlane's real estate had skyrocketed to $83,000; his personal estate was estimated

at $7,000. Eight of the children (all but John), ages twenty-one to thirty-two, still remained at home,

along with four new Irish servants.

Although the younger of the sisters, Julia was the first to publish a children's book and to begin

the sisters' long association with Robert Carter & Brothers. She may have submitted the manuscript to

Carter's publishing house because Carter, a staunch Presbyterian, had a reputation for publishing moral

and religious works; fifteen years earlier, his firm had even issued one of her father's books (The Bible

and Civil Government). Moreover, Carter's firm had a flourishing line of children's books ("the most extensive

ever issued by a single house," observes one publishing history), primarily geared toward a Sunday School

market.[6] Julia's Little Katy and Jolly Jim, published in 1865 -- apparently

anonymously -- was her first children's book, and possibly her first book publication. (An 1855 novel,

Lily Huson, is often attributed to her, but the attribution is probably an error.) The sequel,

Jolly and Katy in the Country, appeared the same year. The two books carried identical dedications,

to her mother, "whose dear hand guided me into the fold of the good shepherd," and were issued

"with the earnest hope that through [their] pages some other wanderer may be led into the same safe fold."

The following year the prolific Julia completed Nellie's Stumbling-Block (later bundled into a

catch-all series, Dare To Do Right) and the six small volumes comprising the Golden Ladder series

(sometimes reprinted in one volume as Nettie's Mission, the title of the first book). In addition to their

American publication, all of Julia's books were reissued in the United Kingdom by James Nisbet,

either anonymously or under the pseudonym Alice Gray.[7]

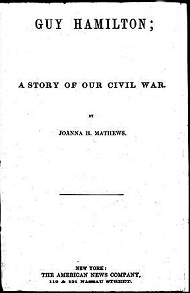

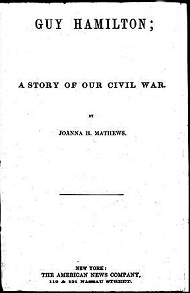

Joanna's first identified publication in 1866 gave no indication of the direction of her future

works. Guy Hamilton: A Novel of the Civil War was issued in an inexpensive paper edition by the

American News Company and aimed at an adult audience. [8] Her next book, Bessie at the Sea-Side, published

in late 1867 (and retailing for $1.25, more than twice the price of Guy), truly launched her career.

The story featured the episodic adventures of precocious five-year-old Bessie Bradford, her seven-year-old

sister Maggie, and, occasionally, their siblings. At a time when many authors were moving away from

proselytizing child protagonists, Joanna created characters who frequently spoke about their faith and

influenced others yet also engaged in childish play and sometimes misbehaved. One source states that

Bessie was supposedly "composed without thought of publication" and "was purely imaginary, based on no

special incidents of which she had any knowledge," created while Joanna was "trying to wile away the tedium

of a sick room to which she was confined." [9] (Those circumstances may account for the dedication in the

sequel, "To the Children of Dr. John Murray Carnochan, the kind friend and physician to whose skill and

patience I owe a life-long debt of gratitude.") Like her sister, Joanna dedicated her first children's book

to her mother, and, like her sister, had the work published by Robert Carter (and by Nisbet in the United

Kingdom). By the end of 1868, Joanna had added two more volumes about Bessie, and Carter started

advertising them under the heading "The Bessie Books." Even though the series ended in 1870 when it

reached six volumes (a standard length for series during the era), for the rest of Mathews's life -- and

in her obituary -- she would be remembered as the author of "The Bessie Books."

The 1870 census, taken mid-year, found the the family still in New York City. James Mathews had died

in January, and sixty-four-year-old Ann was now the head of the household, with real estate valued at $40,000.

All seven daughters were still unmarried and sharing her home. Even though Julia and Joanna were

publishing steadily, no one in the family lists an occupation.

During the next decade, Joanna and Julia continued writing. In 1870, along with a stand-alone title,

Julia started a six-volume series for boys, Drayton Hall, dedicated "to the memory of my father," and

completed it the following year. After 1871, her writing pattern changed: For the next few years, rather

than publishing books she contributed occasional poems, essays, and short stories to the American Tract

Society's newly established periodical, The Illustrated Christian Weekly, and may have been submitting

material to other periodicals as well.[10] In 1876, Carter published two non-series

volumes, both later bundled

into the Haps and Mishaps series with four titles by Joanna. Julia's final two books were issued by a

different publisher, Roberts Brothers. Although the second of these, Bessie Harrington's Venture

(1878), was advertised as "A Novel . . . her first effort in mature fiction," it was generally reviewed

with children's books, and its British publisher, Nisbet, included the volume in his School Girl Series.

Joanna also was proving astonishingly prolific: all six volumes of her Flowerets series, based on the

Commandments, appeared in 1870; 1871 saw the first two volumes of Little Sunbeams, the last four of which

appeared in 1872, along with the first three volumes of the Kitty and Lulu series. The remaining three

volumes of Kitty and Lulu were published in 1873, as was Fanny's Birthday Gift, the initial volume of

Miss Ashton's Girls. Were that not enough, Joanna had three short stories and a poem published in the

Illustrated Christian Weekly in 1871-72.[11] The poem, "Mischievous Daisy,"

was one of two "Daisy" poems, both written as if spoken by a very small child and filled with

mispronunciations. ("Down in de b'ight deen meadow/De pitty daisies' home--" begins the other,

"Daisy's Faith.") The original publication date of "Daisy's Faith" has not been located, but Mathews

appears to have caught the fancy of the era, for it was included in several anthologies for recitations

between 1875 and 1912.[12]

At some point during this period of productivity, probably 1873 or 1874, the Mathews family moved to

Summit, New Jersey, where Joanna and Julia remained for the rest of their lives. The 1880 census showed Ann

still headed the household, which included six of her daughters (all but Gertrude) and two Irish servants.

Only one daughter, Caroline, had married; her husband and their four-year-old son shared the Matthews' home.

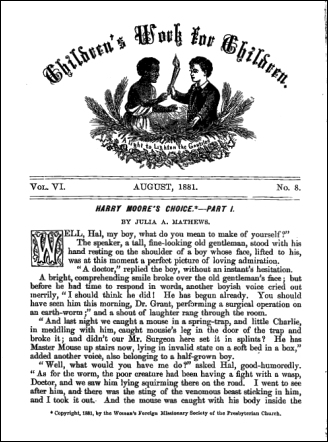

Although some sources erroneously date Julia's death as 1900, it actually occurred August 7, 1881,

in Summit. Her death certificate lists pelvic cellulitis as the cause and suggests she had been ill for the

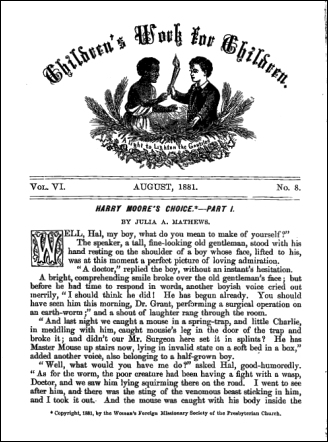

past four years. Ironically, that same month Woman's Work, a publication of the Women's Foreign

Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church, announced the start of a new serial, "Harry Moore's Choice,"

by Julia in their

sister publication, Children's Work; the notice explained that Julia had "consented to be a regular

contributor to that magazine." Three months later, Woman's Work reported that "the last part of a

serial written by this gifted author . . . among the very last of her writings" would appear in the

October Children's Work. [13] One of the only other indications of Julia's

passing appeared two years later in the Illustrated Christian Weekly: it reprinted her Christmas poem,

"The Little Minstrel," in the December 22, 1883, issue, this time as "by the Late Julia A. Mathews."

(The poem also ran in the Friends' Review in 1884 with the attribution intact but Mathews'

surname misspelled.) [14] In 1883, the Presbyterian Board of Publication included one

of her short stories in Harry Moore's Choice. With Other Missionary Stories. Although the book is

often listed under Julia's name, only the title story is her work.

During the 1870s, Joanna had been writing steadily, adding five volumes to the Miss Ashton's Girls

series in 1874-75 and producing the four titles grouped as the Haps and Mishaps series between 1876-78.

About 1878, both sisters appear to have had a falling out with Robert Carter, for Milly's Whims (1878)

in the Haps and Mishaps series was Joanna's final work for Carter. Unlike Julia, Joanna seems to have had

difficulty finding a satisfactory publisher: in 1878, her novel Edith Murray was issued by Dillingham;

in 1878-79, she had two works published by the American Tract Society; in 1880, Lothrop issued her Breakfast

for Two, and Dutton, her Belle's Pink Boots (the latter illustrated by the popular Ida Waugh).

In 1881, Joanna returned to writing stories about the characters from the Bessie books -- but for Cassell,

Petter, Galpin & Co. Her initial offering was Bessie Bradford's Secret, then, emulating her late

sister, she also tried her hand at books with male protagonists, featuring Bessie's brothers in Fred

Bradford's Debt (1882) and Harry Bradford's Crusade (1883). A four-year hiatus followed, after

which time Joanna found yet another publisher, Frederick A. Stokes, for two linked titles,

Uncle Rutherford's Attic (1887) and Uncle Rutherford's Nieces (1888).

In 1889, publisher Robert Carter died, and the following year the firm closed, selling off most of its

plates. Even though Joanna was now writing new Bradford stories for Stokes, the firm of DeWolfe Fiske

acquired the rights to the original Bessie series and reprinted them in 1890, resulting in four different

publishers all printing books about the same set of characters within a decade. [15]

(In 1900, yet another publisher, Caldwell, would reissue the original six Bessie books.)

Joanna's last children's book, Frankie Bradford's Bear, was published in 1893. That same year she

also compiled A Short History of the Orphan Asylum Society in the City of New York, an organization

of which she was a member. The brief accounts of Joanna's life in her obituaries note that she "kept a

large circle of friends" in New York City and "up to the last few months of her life," was active in her

community and "most useful in promoting all plans made for benevolent enterprise and town improvement." [16]

Although few specifics are available, an 1895 New York Times article mentions her work in Summit for the

Annual Fair for the Fresh Air and Convalescent Home: appropriately enough, she was in charge of books.[17]

A piece in the Summit Herald carries the additional information that "she was one of the promoters of

the old Village Improvement Society" and later became "deeply interested in the Town Improvement

Association." [18] Early in 1901 Joanna became ill and spent "four months suffering

from an illness" described as "simply a continual decline." She died in Summit on April 28, 1901, and, like

Julia, was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City.

Notes

This essay originally appeared in the August 2012 issue of Dime Novel Round-Up

as "Joanna H. Mathews and Julia A. Mathews."

Illustrations have been added to the web version, and some minor modifications made. Another version, without

illustrations, is available as "Joanna Hone Mathews

and Julia Anton Mathews: Sisterhood and Sunday School

Books", Digital Commons@West Chester University

1. "Mathews, Joanna Hooe [sic]," Who's Who in America: A Biographical Dictionary of

Living Men and Women in the United States, 1899-1900 (Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Company, 1899): 479,

Google Books; "Joanna Hone Mathews," New York Times (April 30, 1901): 9,

ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

2. Kathryn Greenthal, "The Reverend James M. Mathews: A Possible Attribution to John Wesley

Jarvis (1780-1840)," The American Art Journal (October 1979): 91; New York University 1832-1932, ed.

Theodore Francis Jones (NY: NYUP, 1933): 61, Internet Archive; "Mathews, James Macfarlane,"

The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans, vol. 7 (Boston: The Biographical

Society, 1904), Google Books. Ruby Marlatt, Ancestry World Tree Project: Stouten, Ancestry.com

3. Biographical Catalogue of the Chancellors, Professors and Graduates of the Department of Arts

and Science of the University of the City of New York (New York: Alumni Association, 1894): 231,

Google Books.

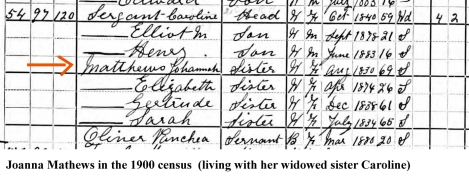

4. While Joanna's 1900 census entry gives her age as 69 and her birthdate as August 1830, she is 22

in the 1850 census; 32, in 1860; and 42, in 1870. Her birthdate is not the only error in most biographical

entries. As often happened in the nineteenth century, Joanna received her mother's maiden name, Hone, as

her middle name. Somehow, this became Hooe in her Who's Who entry, and many of her books are currently

catalogued as by Joanna Hooe Mathews, 1849-1901. Information about Julia's age is also from the census

records.

5. Who's Who.

6. John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United States, vol. 1 (New York: R. R.

Bowker, 1972): 330.

7. The ten-year gap between Lily Huson and Little Katy is but one reason for questioning

Mathews's authorship of Lily (which would thus have appeared when she was about nineteen). Presumably,

Lily has been assigned to Mathews because it appeared with Alice Gray as author, and Mathews sometimes

used the pseudonym Alice Gray (or Grey). Although a number of Julia Mathews's children's books were later

reissued with her name on the

title page, she does not appear to have been associated with Lily Huson until A Supplement to

Allibone's Critical Dictionary of English Literature and British and American Authors, vol. 2

(Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1899) -- published after her death -- credited her with it and

Clara Neville and Other Tales (p. 1090). Clara Neville and Other Tales -- apparently

published in same volume as Lily Huson -- carried the notice that the stories were "by the author

of 'Lily Huson.'" Several of the stories included headnotes claiming they were based on the author's life;

that this was purely a literary conceit is made clear by the headnote to the second story, which mentions

that some of the subsequent stories "relate to events which occurred in England. It is sufficient to say,

in order to explain this, that the author is, on her father's side, of English descent" (254) Three of the

stories involved, however, ("The Ruined House," "My Father's Head Farming Man; or, Peter Mulroon's

Adventures," and "Save Me From My Friends") are either modified or taken directly from three stories

("The Razed House," "Phil Flannigan's Adventures," and "Save Me From My Friends!" -- the latter with

George Raymond as author) in the British Bentley's Miscellany 11 from 1842, and "Clara Neville" is

taken from Harry Mowbray (London, 1843) with the names and locations altered. Thus, none of the

titles attributed to the author of Lily Huson are Mathews's work.

It should also be noted that a "Miss Alice Gray" published stories in Peterson's Magazine from

1852 through 1878. Their contents -- some travel pieces in a flippant tone, some romances -- seem very

different from Julia Mathews' works; whether she has any connection with these pieces remains unknown.

8. Online at Wright

American Fiction, Indiana University.

9. "Book Notices," [review of Uncle Rutherford's Attic ], Magazine of American

History 18.5 (November 1887): 456, Google Books. At least one passage in Sea-Side,

however, is taken from a real incident, for it has the footnote "Almost the exaxt words of a very lovely

child of a friend of the writer" (Joanna H. Mathews, Bessie at the Sea-Side [London: James Nisbet &

Co., 1868]: 123, Google Books ).

10. See, for example, "Ye Are of God," in the September 2, 1871, issue; "Christ's Invitation to the

Children," November 25, 1871; or "A Christmas Hymn," December 28, 1872. In 1874, the American Tract

Society also issued a small volume comprised of two short stories, Joanna's "Benny; or, The Boy Who Was

Always Right" and Julia's "Mother's Honest Little Boy, " both of which had appeared in the Weekly and

possibly elsewhere.

11. "Robbie's Shield," August 5, 1871; "Mischievous Daisy," March 16, 1872; "Johnny and the Gingercake,"

May 25, 1872, "Benny the Boy Who Was Always Right," September 7, 1872.

12. "Daisy's Faith" appears in The Reading Club and Handy Speaker no. 8, ed. George M. Baker

(Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1880): 65-67; (reprinted as Pieces People Praise [Boston: Walter H. Baker &

Co., 1912], with an original copyright of 1875 as The Reading Club, no. 3); Cumnock's School

Speaker: Rhetorical Recitations for Boys and Girls (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Company, 1888): 90-93;

Best Things from Best Authors, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: Penn Publishing Company, 1900): 42-45

(originally issued as Shoemaker's Best Selections, nos. 7-9, in 1881); and The Speaker's Garland,

vol. 5 (Philadelphia: Penn Publishing Company, 1910): 76-78, all Google Books.

13. "The Fruit of the Spirit," Woman's Work for Woman 11 (1881): 281; "Miss Julia A.

Mathews," Woman's Work for Woman 11 (1881): 331, both Google Books.

14. Friends' Review 37 (1884): 463, Google Books.

15. "Sale of Robert Carter & Brothers' Plates," Publishers' Weekly, October 11, 1890: 535, 537;

"Business Notes," Publishers' Weekly, December 6, 1890: 929, Google Books.

16. "Miss Joanna H. Mathews," New York Tribune, April 30, 1901: 7, Chronicling America.

17. "Summit's Social Doings," New York Times, June 16, 1895: 11, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

18. Obituary for Joanna Mathews. Summit Herald, May 4, 1901, msg. pg. Quoted material in the next

sentence is also from this source. The author wishes to express her gratitude to Nancy Boucher and the

Summit Historical Society for providing a photocopy of this clipping.