The following article, published in the Boston Globe on October 14, 1894, offers not only a look at Mrs. Bruce's unusual home but also her equally unusual ministry. Moreover, although biographical details are slight, it's clear that that Bruce's life and family influenced the decoration of her home and chapel.

The chapel remained open until Bruce's death in 1911. The Universalist Register estimated that ultimately more than 80,000 people had attended one of her services.

A photograph of the chapel appears in Percy Metcalf Leavitt's Souvenir Portfolio of Universalist Churches in Massachusetts, which identifies it as the Wayside Mission.

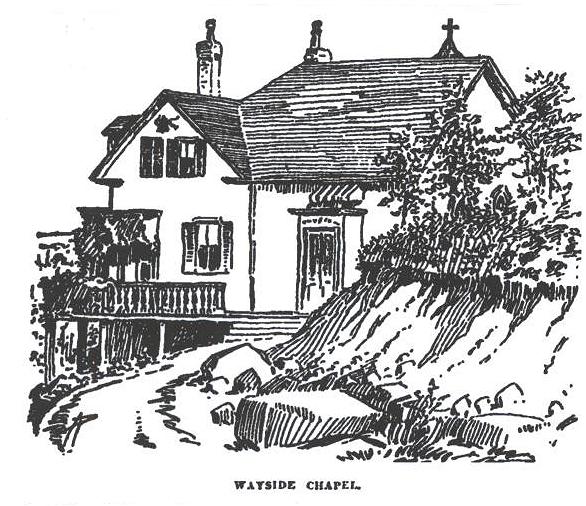

The private dwelling of Mrs Bruce is plain outside and is hidden among bolders [sic] and wild shrubs and trees on the brow of a very high bluff on [illegible] in Malden, looking seaward.

It is named "Manitoba," which may be interpreted "quiet for the careworn." And because it contains a little chapel wherein a woman holds vesper services for wayfarers six days in the week, and preaches a regular sermon on Sunday, it is quite different from all the dwellings you ever heard of. It is singularly notable in many other ways.

From the gravel road which ends at the five chapel steps, you can see the gilded cross on the cupola and the chapel bell aloft under the peak where the eaves meet; and, if you are near enough, you may read over one of the two small doors, "Wayside Chapel."

Running half way around the house there is a verandah, whereon persons may walk in single file only. If you are curious or devout or down-hearted, follow it to the second door, and ring.

A day or two ago a frail old lady opened that door to the artist and this writer. She was dressed plainly in black, and at her waist was a girdle of brown beads and a cross that tinked with each step as she led the way into the parlor.

Her face was lightly seamed with wrinkles and serene and gentle. And her eyes were dark and looked kindness and sympathy. Once she must have been pretty. She spoke in soft, low tones, without effort, and her words were pleasant to hear. The rocking chair in which she sat was old-fashioned, and around her all about and about, misty in the dim light, were quaint pictures and crooked legged chairs and queer little tables and bric-a-brac; so, in the black dress with the rosary girdle, she looked like a person of another time, a character in history, some one quite out of touch with today and its peculiar tribulations.

That was all a wondrous illusion. This old lady knows quite as much about the doings of the hour as you do. Likely, more.

Every day, just after breakfast, she comes down from the hill and visits the sick and poor and disconsolate of two cities. In Malden the almshouse profits by her once or twice a week, and to all the public schools she makes regular trips during the winter.

She calls often at the Charleston prison and speaks with the prisoners. And all over Boston she ministers to the unfortunate, bringing clothes or food or money. She moves in and out of the homes of the destitute unnoticed, unprotected. She works without show, carries no banner. But many a poor waif would run to kiss the edge of her skirt; many a downcast soul has lived over the hard places under her gentle guidance.

And in all her merciful work this old lady is unaided. Of money she must have an ample store. Of near relatives she cannot have any: at least, few people know of them. They say that Mrs. Bruce was born somewhere in New York; that her husband was a Universalist minister who, some time before he died, taught school with his wife as assistant, and that it was a sister who left to Mrs. Bruce her money.

The last, however, cannot be sworn to by anyone except the payee. One thing is certain. Mrs. Elizabeth M. Bruce was, about three years ago, by and in the presence of an old Universalist clergyman in Boston, regularly ordained a minister. But to go back to the parlor.

The old lady rose from her rocking chair.

"You have come," said she, "to see the chapel and to look through my house; and since I have spare time and am alone, you may do both. But first the chapel, which is the very next room."

Forthwith began a tour; in memory, thus:

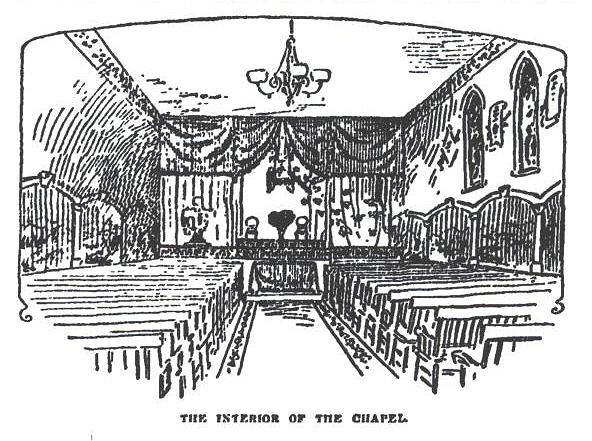

The room is square; and in the afternoon the light in it is pink, being strained through three stained glass memorial windows, whose figures illustrated the lives of two sisters and a brother. There is a high little platform at one end, curtained like the stage of a Turkish theater, and in the center is an altar, whereon a great Bible lies open. The floor of this odd pulpit is soft with many mats and white rugs, and rising up from the right of it, behind a veil that cheats the eye, are 50 white doves, both large and small.

They stretch up and up, along a tiny gilded stair piece, to a half open window, where the image of an angel beckons toward the sunlight. The chapel walls are paneled with seven paintings four feet square, crudely done in places, but evidence of serious labor and no mean imagination, and they tell a story around the room to the white doves, so [sic]

"Those ships," said the old lady, extending a thin steady hand to a picture of vessels in a narrow strait between mountains, "are sailing the voyage of life. There, youth is buoyant in a careless sea, but the passage between the mountains is shadowed; a storm is coming. In the next, some have gone out safely through the passage; the unheeding remain. In this one, the storm rages. The wayward ships are tossing in trouble, but some are wisely making for the narrow passage. Here, the heeding ones are well on their course, but difficulties beset them. It is so in the next one, but the reward of diligence is awaiting; the waters are getting smoother. It is so in the next, and the harbor is in sight. In the last, you see, the course is run, dangers are passed, life's journey is ended; and the souls aboard are soaring up, up to the gate where the Pilot of the Unseen stands beckoning receiving them into the glorious home whence they came."

Her face were sweetly radiant in the pink light.

"Those flowers on the curtains," said she, "represent christening. I pin up a fresh one whenever a baby is brought to the chapel. See, there are many. On next Sunday, I shall hang up one more. Those other flowers, those lilies pinned in pairs about the room, represent chapel marriages. But the white doves are for the souls of the dead that I have ministered to. One for each soul; neither more nor less; and the little doves are for children."

There are settees in rows on the chapel floor, perhaps 20 of them, all seated with cloth worked with flowers; and on the back of every settee is a motto from Scripture.

The aisle between is laid with a strip of brussels bordered with flowers and scrolls beautifully worked on a white woolen ground.

"Those I did myself with a needle," Mrs. Bruce said. "I painted the mottoes on the settees and the seven pictures on the walls. In seven weeks I finished them."

But that is not all. She lettered two memorial tablets between the windows and painted a border of flowers clear around the room high up on the walls; and she built the altar, the pulpit and the gilded stair piece. She fashioned everything in the chapel, and a great deal more -- all alone.

"I have neither house companion nor servant, nor dog nor cat," the old lady said, contentedly, too. "My thoughts are my companions; my hands are my workmen and my recreation is the adornment of my house."

And this old lady with the gentle eyes and the girdle of beads is sane, as sane as ever woman was.

Every day in the week at 20 minutes of 5 the chapel bell, outside under the peak of the eaves, rings out mellow and clear; and devout folk stroll along the gravel road and enter the chapel. Sweet music is somewhere in the pink light, but no man can trace its source.

At 5 the bell tolls again. The vesper hour begins and the wayfarers within kneel in silence. On some days only two or three are there in the pink light. The soft strains of "Sweet Bye and Bye" fill the air and the white doves behind the veil move their wings and seem to be soaring up, up, toward the sunlight. The music ceases, and the old lady ascends the pulpit from behind the curtain and kneels at the altar.

Follow prayer, the singing in unison of a hymn or two, reading, more singing, and the benediction. Then the service is over -- just 15 minutes of silent communion and praise giving -- and a kiss on the cheek from the gentle old lady as you go out the door. That is quite enough for you to know now.

"On the 30th -- next Sunday -- I shall be 64 years of age," Mrs. Bruce was saying, as we followed her from the chapel, through the parlor, in back to a door with hand-painted panels. "I have lived in this house for 16 years almost continually alone, and four years ago I built the chapel. Yes -- I made it all.

"I have made many things -- see, all these carpets and mats, and every painting of any description throughout the house. I have a saw and a hammer and other implements -- other paythings. [sic] I cook and eat alone. Come, this is my kitchen."

It is a little, very little room with a stove in it as high as your knee and lids as large as tea saucers, clean and neat and snug. A thick rug covered the floor and a small door opened into the dining room.

The panels are painted to represent grapes and apples, and carrots and beets and cucumbers. The round table in the dining room was set with small white mats, hand-made and pretty. Nearby a cupboard, or sideboard, or whatever it was, contained spotless dishes, and a few pieces of plate, polished bright. As we surveyed with interest all things, Mrs. Bruce described and entertained.

But she was never garrulous, nor did her talk seem at all stereotyped, though she has gone the rounds of the house for the edification of some 40,000 visitors.

We descended into the depths of the cellar by a narrow carpeted stairway, over which, on a shelf, was a loaf of bread and a pie. Perhaps this shelf was the pantry. There were dishes on it. In the basement two rooms are floored with clean straw mats, and the walls are paneled with more of those queer life-history pictures, all hand work.

In one room -- Mrs. Bruce has named it the "cellar parlor" -- the panels told the story of a woman's life -- childhood, youth, merrymaking, trouble, dire trouble, a long journey, exhaustion, rays of hope, ultimate blessing. The whole panorama was a sort of homely allegory, or a "Pilgrim's Progress." Folks who generally know things assert in a whisper that these pictures portray actual links in the life of this gentle old lady.

They say in a softer whisper that she has had sore misfortune, and that the truth of these would move a stone to tears. That is, they say.

"The next room," said Mrs. Bruce, "is the gallery of funny things. See, here are merry, naughty boys; a cat frisking over the stone wall with its tail in fine perspective with the mischievous pup's mouth. Here a squirrel has stolen corn from the field and feels queer pains which makes his face wry. There in that castle window at the foot of the stairs is an owl, watchful and very solemn. Shall we go into the upper parts of the house now?"

Back up the carpeted cellar stairs, through the parlor and up more stairs, she led us, quite actively, too, and paused in a room that seemed to be like the rooms in ordinary houses; at least, modern. Perhaps it was so because 500 books, gilt-lettered and of different colors, stood evenly in a modern bookcase. The carpet, too, was like others that we had trod on.

"This is my study," said Mrs. Bruce, "and this mite of a room here is my writing room. In these cloth pockets along the base-board, see, I have cuttings from papers and selections from all kinds of the best literature of the world. For 16 years I have collected them and, see, I can find any reference in a moment. From that wee window I get light enough to read and write; but the room will hold but one person, and a short one at that."

From the study walls I took down this -- it was painted in black:

My Creed:

I love God.

I trust Humanity.

I believe in the rectitude of my own intentions.

Under portières we passed from the "study" into the "studio." Excepting the chapel and the pink light this is the unique of all uniques. To name simply all the objects in the room would make a list longer than three columns in this paper.

Every conceivable thing of quaintness is on the floor or mantels or doors or tacked to the walls. Nowhere can you find even a square inch of wall uncovered.

The whole carpet -- the room is not small -- is hand-made and extremely fine and beautiful work. Over 200 gilt-framed paintings -- no less -- are hung about. There is a cuckoo clock in a corner; a stuffed owl is in another; there is a huge hourglass on a mantel packed with queer little pictures and boxes and trinkets. Countless bits of lace and pencil sketches and shells are pinned everywhere. Flowers are in the windows and a skylight has lace curtains fastened with a trailing ivy.

We were afraid to turn around for fear of knocking some treasured knick-knack out of place. No museum ever was so strangely arrayed or so skillfully packed. And every single corner and crevice was wondrous clean. "Mrs. Bruce," said one, "If you should ever want to move --"

"Move," she said, smiling. "In this room is the earthly story of all my life. You see it is full of incident, replete with what seem to be trifles; they are priceless as life-drops. Every little bit is a symbol of some event in my life. The symbols, you see, are myriad. And but one person in the world can interpret them."

All of which might mean that her life is the mystery of mysteries. No doubt it is.

"This room," she said, "is a playhouse to me and a weeping ground. The whole house is a doll house to you. Do you know that my one regret is that I didn't build the house with my own hands. The carpenter, who comes now and then to patch up a leak in the roof, says that his one satisfaction is that I cannot get out on the roof.

"I envy him -- of course, pleasantly. That book you are looking at contains photographs which I myself have taken. I have a camera and develop my own plates. There, that is a picture I took of myself before the mirror in the bedroom -- in -- this way."

This bed chamber is about as cozy as any you would care to sleep in. It is blue-tinted and floored with straw matting and modern, nearly. It would be so if you removed from the walls and mantels hundreds of trinkets and old-fashioned bric-a-brac. Over the door is the morning motto:

"Wake with Thanksgiving. Guidance Seek; Since Dawning Brings Responsibility and Questioning."

Over another door is the night motto: "To Trusting Listeners the Voices of the Night are Kind."

Now this is the only bed chamber in all that lonely house, and it contains but one bed. The night motto would seem, therefore, to be especially in order.

"In all the 16 years I have resided here," Mrs. Bruce said, "I have never once been frightened."

She then led us out of the bedroom and up a curious stairway, along which no fat person could squeeze. It was for all the world a miniature of the attic staircase in the "House of the Seven Gables" at Salem, and led us to a bare square room, with ceiling and walls of colored cotton. From that the old lady led us up into the cupola, the cupola with the cross that can be seen from the gravel road.

It is an odd little den with three satin-curtained windows and a vaulted ceiling painted to represent a star-lit night, with a rift in the sky letting in a spring of passion flower. Three baby chairs are on the floor and there is a pair of field-glasses for your service on a tiny shelf. Through them we looked down upon Malden -- card-like houses set in straight, pretty rows -- and 20 other town and meadows; and off to the east, a blue streak on the edge of the green, was the sea and many ships. A legend clings about the cupola, thus:

"One night, it was the last in the year," said the old lady, "I took out my record book and looked through it to see whether I had accomplished all that I had planned for that year. I believed that I had not, and I was dejected. So I went to bed. In the night I dreamed a strange dream. I was in a greenhouse.

"But the flowers were all withered and desolate. So I watered them with a pot. They did not brighten, and I was heart-sore. In my distress, I heard a voice calling, 'Look up.' It was the voice of my father, as plain as I had ever heard it. There was a rift of the starlit sky, and through it hung some fresh, beautiful passion flowers -- and I knew then that the life of all things comes from above. So I have put the dream here in this dome -- far away from the world -- with only the sky between it and the life source."

We tarried awhile, then descended. Going through the queer, still, mysterious rooms again we felt that we had never before seen them -- they were so wrapped in unfathomable quaintness. The very air in them seemed heavy and solemn, and the pink light in the chapel was saddening. But the face of the gentle old lady with the tinking girdle of beads was cheery. And as she grasped our hands at the door, it seemed to be radiant with a new warmth, a new kindliness.

-- Boston Globe, Oct 14, 1894: 25